By Tanisha Brown and Brandi Costain

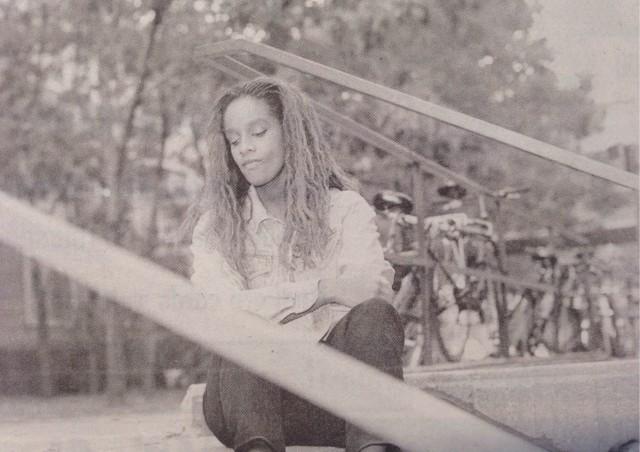

When Grace Asamoah looks in the mirror, she thinks the image that stares back is a disgrace.

The 16-year-old’s naturally kinky hair, pinched back into a ponytail, broad nose, full lips, dark eyes and even darker skin all scream on thing to her: “You’re ugly.” They’re the reason why she applies ivory powder to her ebony skin. In her mind, her dark skin is undesirable. She wishes she could have lighter skin or even better, be white. But she knows her dream of looking like the females on television will never come true.

“Everyone I see on TV and in advertisements is white or light-skinned. These images tell me what I am ugly, that my dark skin isn’t good enough and that I don’t belong,” Asamoah says.

In April of this year, a study done by Tufts University in Massachusetts, found that skin tone stereotypes that Asamoah believes about herself are shared by many young adults.

The study, “Cognitive Representations of Black Americans: Re-exploring the Role of Skin Tone”, found that racial prejudice is related to the lightness or darkness of a black person’s skin (both men and women), not other features such as hair length or texture, fullness of lips or the width of a person’s nose.

Prior research had only studies cultural stereotypes of blacks in general, but Keith Maddox, assistant professor of psychology and head of tuft’s social cognition lab, found that there exist cultural stereotypes based on the skin tone of blacks.

In the first part, of the study, 150 black and white college students were shown photos of blacks with various skin tones. Characteristics were printed beneath the photos. In a later test of memory, they matched the characteristics with the photographs. The researchers ensured that the categorizations were based on skin tone rather than facial features by altering the lightness and darkness of skin tone in the photos.

In the second part, the students listed characteristics they thought were associated with dark-skinned and light-skinned blacks. Maddox says that blacks and whites associate intelligence, motivation and attraction to light-skinned blacks and poverty or unattractiveness to dark-skinned blacks.

Asamoah admits that she has low self-esteem, but her desire to have light skin is a case of internalized racism. In elementary school she was called “gorilla” and “tar baby,” and remembers the boys in her class rating her on her looks — she was given a minus 1000 because she was so dark.

Now in high school, Asamoah is called “white-washed” by her peers because she “acts white” and only has light or white friends. Asamoah believes that being called “white-washed” is far better than the other names she has heard and that nothing could ever be worse than the time a boy told her she looked like, and was just as funny as, Whoopi Goldberg.

“It really hurt. I cried myself to sleep,” Asamoah says. “She’s successful and all but when people say you look like her, you know you don’t look good. I want to look like Halle Berry. She doesn’t get made fun of.”

Asamoah and her mother moved to Toronto from Togo, Ghana in 1992. She remembers how “nice” it was in Ghana because all the kids of different shades would play together without mention of colour, but how, at the same time, her mother would constantly belittle dark-skinned people. Asamoah says this only got worse after she moved to Toronto and her parents divorces.

“[My mother] tells me that dark-skinned men are no good,” says Asamoah. “She sees how happy her friends are with their white husbands and she wants to be like them, she wants to have money and status without the struggle. Being as black as we are, the only way to do that is to marry a white man.”

Asamoah’s experiences with skin tone bias and stereotypes dates back to when she came to Canada, but according to experts, it has been around since slavery.

Yvonne Bobb-Smith, a lecturer in Caribbean studies, says that skin tone bias stems from a historical capitalist system where black women were sexually exploited and forced to have intercourse with white men. This resulted in many black people being born with lighter skin.

“White people created a hierarchy where a mixed race group of people made up a specific social and economic group in society. At the same time, people with dark skin were still enslaved,” she says. “It was very difficult to find dark-skinned people who were doing economically well.”

Bobb-Smith says a system existed where light-skinned people were seen as more attractive and were given financial opportunities over dark-skinned people.

She explains that those with dark skin wanted to improve their status in society, so they mixed races and married different groups in hopes of improving the lives of their children.

In The Color Complex: The Politics of Skin Color Among African Americans, author Kathy Russel writes that during times of slavery, white plantation owners became sexually and emotionally involved with black female slaves and were just as attached to their bi-racial children.

She explains that some plantation owners freed their mixed sons and daughters and helped them to start businesses. White legislators also fathered mixed children and were known to affect political policy for the benefit of the mixed population. As a result, Russel says that mixed blacks in the South obtained the status of a separate coloured class.

“A three-tiered system evolved in the lower South, with mulattos serving as a buffer class between whites and blacks. Members of the white elite found advantages of this arrangement,” she says.

“Necessary business transactions between the races could be conducted through mulattos, whose presence reduced racial tensions, especially in areas where negroes outnumbered whites.”

Russel says that after the American Civil War both light- and dark-skinned slaves were freed and skin-tone discrimination developed between the two groups.

“To preserve their status this coloured elite began to segregate themselves into a separate community. In the process they actively discriminated against their darker-skinned brethren,” she says.

According to Russell, the coloured elite acted the same as any other upper-class group in attempting to secure their status. But, instead of money, skin colour determined who would be accepted.

Ryerson student Kedane Aleph says he never thought about the type of black women he dated, but admits he’s only attracted to those who are light-skinned.

“Something catches your eye when you see a light-skinned girl as opposed to a dark-skinned girl,” the third-year social work student says.

“I try to look at black women on a universal level and not to cite skin tones, but I notice that there is a preference towards light skin, thin lips and so on.”

Aleph says that skin tone bias has determined the type of women he has dated or approached in the past. He says the difference in the way dark- and light-skinned women are treated is similar to what is seen in many cultures where people with fairer complexions have more advantages.

“It’s a caste system or pyramid that you see in most cultures where light skin is at the top and dark skin tone is at the bottom. It’s a system that makes you think that whiteness is better and blackness is soiled,” he says.

Aleph adds that he noticed that when he was dating women with lighter skin tones, his friends thought highly of him.

“When you are talking to someone with a lighter skin tone, people around you give you more compliments about her. I see it as just a product of society,” he says. “It’s just kind of sad to see that you are put on a sort of pedestal if you are dating someone of a lighter skin tone.”

Charmaine Crawford, the co-ordinator of the African Canadian Coalition against Racism, says that black people need to start affirming themselves and those around them, as well as having positive images within the home.

“Stop telling people they’re too black or that their lips or butt is too big and embrace our multiplicity,” she says. “We need black dolls, artifacts, paintings and books in our homes that promote the beauty of blackness.”

This also means that the blacks in media and entertainment industries need to stop projecting the image of one particular woman as ideal.

“Black Entertainment Television [BET] and all those music videos show you how far we haven’t come in appreciating our diversity,” she says.

“They keep on showing the same kind of girl making it seem that only one type of girl is beautiful and can be successful and loved.”

But Asamoah wants to be that girl. She says that her mother is now with a white man and they are planning to have a baby. Her mother tells her that in order to be successful, she must do the same.

“My mother told me she wouldn’t come to my wedding if I married a black man. She says I need to lighten up our family and our race,” she says.

“She’s doing it with her fiancé and I will be so jealous when the baby comes — it will have light skin, it will be living my fantasy.”

Leave a Reply