By Usman Haque

The first time I felt attracted to her was at an eighth-grade outing, when she came out of the pool and her wet hair flew by my face.

Until then she had just been one of many girls I saw at my parent’s gatherings. We talked occasionally about movies, or where the next dinner party was going to be, but now I definitely wanted more.

The first day of high school came, and from her tan and her relaxed appearance, I could see that the summer had been very good to her. I made a promise to myself that I would eventually express to her my feelings.

It wasn’t just a crush, but rather strong feelings of love. In Pakistani tradition a boy finds love at first sight — and I was sure that she was to be my future wife. She had many traits which appealed to me: She respected the boundaries of our religion, Islam, and she wanted to settle down eventually and have children. She was attractive, knew how to cook, and most importantly, got along great with my parents.

Up until this time I had lived my life very sluggishly, not paying much attention to my physical appearance or condition. I was overweight, my mom was still bathing and dressing me, my back was hunched when I walked, and my legs were getting more bent with each day.

I was born with a condition called Robert’s Syndrome, which left me with shortened arms and legs.

The syndrome is believed to be the result of chromosome damage during cell division. It is characterized by a loss of limb bones, but many other abnormalities can occur from it such as cleft palates and defects of the heart and other organs.

It occurs in varying severity. There are fatal forms, and milder forms as well. Thankfully, I was one of the milder cases and my vital organs were not affected.

Seeing her again at the beginning of high school, I realized I would never be able to care for her if I couldn’t even care properly for myself. I then decided to get my life on the right track; not for myself, but for her.

My parents had always wanted me to lead as normal a life as possible, but my condition was more of a hindrance. As a young child, I only played with the children of my parents’ closest friends.

The time eventually came for me to go to school and meet new people. I still remember pushing my walker into preschool and watching as the other students turned their heads and cried to their mothers or just pointed and stared at my disability.

My only reaction was to start crying myself. The teacher eventually quieted us down and explained to the class that everyone is different and that’s what makes us beautiful.

She then asked me to show everyone how my prosthesis worked and asked other students to how their glasses, braces and other thins that helped them in everyday life. Within the next few weeks, the class began to accept me and even included me in their games.

I am very grateful for those students in elementary school. Rather than crying to their mommies, they came up to me and either insulted me or asked questions. My response to an insult was always “I am rubber and you are glue, whatever you say bounces off of me and sticks to you.”

To this day I prefer direct insults over pointing and whispering behind my back. If someone comes to me with a question about my disability, I will sit them down and explain it to them until they are comfortable with me.

I realize it is the responsibility of parents to teach their children about differences in people, but why do they hush them around me, when the children have an opportunity to ask questions?

Whenever I see a child point at me and ask their parents a question, I try to interrupt their conversation and answer it. I allow the children to shake my hand or touch my prosthesis. I feel it helps them relate to people with disabilities.

Unlike most children who stopped being fed, bathed, and dressed when they were roughly three or four, some of these things were still being done for me.

I put my foot down on bathing and dressing myself when I reached that “special time in every man’s life,” no matter how difficult it would be or how long it would take.

The first day it took almost an hour, the next day I took a shower in forty-five minutes and now I am down to 10-minute showers. I quickly got the hand of putting on shirts and pants but buttons and zippers are still issues for me.

When my friends began getting their learner’s permits and driving licenses, I wanted mine too and was very shocked when my parents said I couldn’t. My mother said I could drive once I improved my walking ability.

Looking back on it, I’m glad I waited. Now I’m able to get up if I fall down, which is something I couldn’t do then.

I got my permit a month after I turned 16, and 11 months later my parents finally agreed to driving lessons. My instructor recommended I have some adaptations made to the car.

A steering cuff was attached to the steering wheel to create a larger distance between my face and the airbag, my key was extended to make it easier to turn, and buttons were added for opening the door and controlling the windshield wipers.

Driving gave me more independence than ever. I was now able to do things for other people; a feeling I had never felt before. I ran errands for my family, and gave rides to my friends.

As kids we often played videogames together, but as we grew older my friends went out more, and I was left to play by myself or spend time with my parents. I stayed at home while my friend ice skated, played laser tag or shot pool.

I had many goals for myself, but they were appearing further and further away because of my inability to walk.

The decision to do something about my legs was very hard to make. Since I was born, my father had wanted me to have something done to improve them, but my mother was concerned about the safety of the procedures.

The average leg can straighten between 170 degrees and 175 degrees, but my legs could only straighten to 120 degrees. Many people in the medical industry refer to a smaller limb as a stump, but I refer to what I have as arms/hands and legs/feet.

My therapists used to say that I didn’t walk, I “fell with style.” I would basically target a wall or door, usually about 20 feet away, run towards it, and then rest against it.

There were a few options for straightening my legs, the first of which was a brace that attached to my thigh and calf and had a crank in the middle. I wore it twice a day for half an hour for almost six months.

I would crank it a few times every five minutes to loosen the tendons behind my knees.

Unfortunately, this system did not straighten my legs at all. But I wasn’t done searching yet.

My orthopaedic surgeon suggested amputation. He felt that my legs had basically “gone beyond the point of no return.” By cutting off the portion of my legs below the knee I might now have to go through a painful straightening procedure, and I might be able to walk more comfortable and efficiently.

There were two main drawbacks: Phantom pains, a sometimes painful symptom which causes a person to feel like their amputated limb is still attached, and the most serious drawback of irreversibility.

One last option, which my orthopaedic surgeon referred to as a painful surgical alternative, was the Ilizarov procedure. The Ilizarov is traditionally used to heal bone fractures and to lengthen bones, but my surgeon was confident it could straighten my legs.

I went in for surgery on November 30, 1999. We decided to do one leg at a time so that I could at least walk on one strong led. Ten hours later I woke up to find my leg inside a metal structure. There were three metal rings connected by thirteen pins and rods which went through my entire leg.

Above my knee there was a nut on a long screw. This nut was turned once or twice a day, slowly straightening my leg at a rate of almost one degree per day. In order to prevent infection where the pins and rods entered the skin, each site had to be cleaned twice a day with a hydrogen peroxide and saline solution, which was initially very painful.

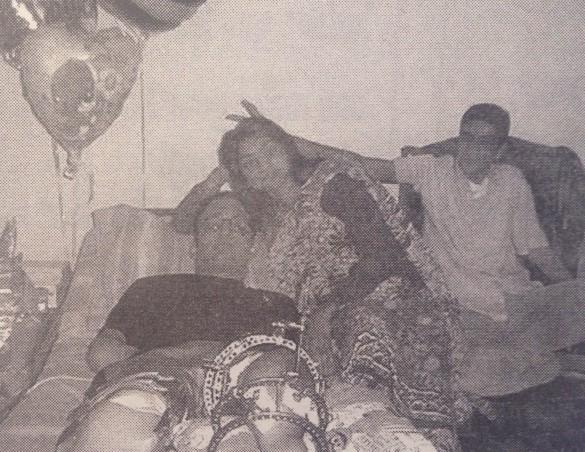

I was overwhelmed at the response from my family and friends. People were constantly visiting me at the hospital and at home, especially my secret crush. She came by almost daily and talked to me, watched TV with me, or just held my hand and consoled me while my pin sites were cleaned.

The frame was finally removed on February 6, 2000 after a pin broke inside of my femur. Luckily I was near the end of the procedure and so I didn’t need to repeat anything.

The following year was filled with countless visits for physical therapy, prosthetic fittings and doctor’s appointments. I had the frame put on the other leg on May 22, 2001. The pin cleanings were more painful than the first time but fortunately the contracture was less severe and the procedure was shorter. The frame was removed on July 6.

I had finally fulfilled one of the promises I had made to myself almost four years earlier. Although I had many years of physical therapy and training ahead of me, I would soon be able to walk more comfortably.

Making the decision to have surgery was more than a big step; it was like climbing a mountain. I had finally reached the top and rather than seeing those other goal as more steps to climb, it was just a matter of running to them; and I would soon be able to. My other goals — independence and weight loss — were now within walking distance.

All the things I previously felt incapable of doing seemed so simple to me; I figured out how to brush my hair, I no longer had to call someone to clean me after using the facilities because I had a bidet, and I finally figured out how to reach my back in the shower, with the aid of shower puffs.

More independent than ever before, I was not ready to tackle my last obstacle: being overweight.

I wasn’t obese but I knew losing weight would help me walk. I was 180 pounds, with a target weight of 150 pounds. Until my legs healed, all I could do was eat less.

By eating less and doing moderate exercise, I lost fifteen pounds in six months. At this point, my legs had healed enough to be able to increase my exercise routine. I started working out in my high school gym and significantly increased my muscle size, making my legs stronger than they had ever been. By graduation I lost another twenty pounds.

Like the other 332 graduates on graduation day, I too was looking back on the events of the last four years. I remembered my father’s glowing eyes when I woke up from my fourth surgery with fully straight legs.

I remembered confidently saying “No thank you,” when my friend asked me if I needed help going to the bathroom. I remembered actually being able to see the scale when I went to weigh myself.

She went up to get her diploma and although she looked as cute as ever in her cap and gown, I realized that she wasn’t the reason for everything I had gone through.

My initial goal at the beginning of high school was to gather enough courage to tell her how I felt, but somewhere between the second and third surgeries I realized that the only person who needed to benefit from my efforts was me.

Leave a Reply