By Farzana Bhatty

“I was sick with malaria. I had lice too,” says Basima Roshan as she twists strands of her short hair between her fingers and describes how she spent her summer as an aid worker in Afghanistan. “My head was really itchy and I knew I had lice. I could actually see them on my pillow.”

She sits comfortable now in white sweat pants and a plan white T-shirt, inside the ILLC lounge at Ryerson.

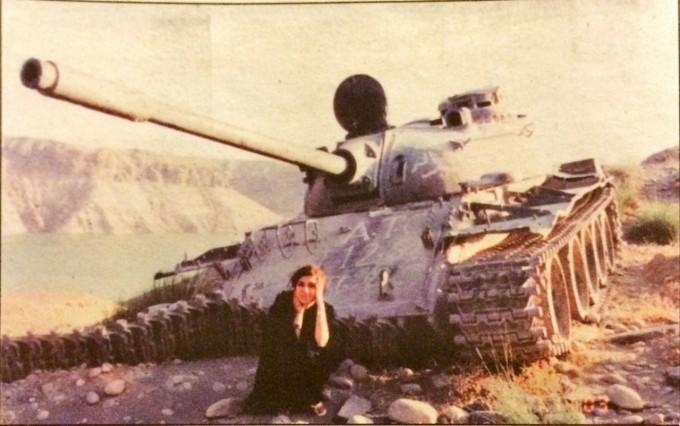

Looking at Roshan, a third-year business management student, one would never guess that she was once an Afghan war child. But after growing up in the eastern town of Jalalabad, Roshan came to Canada in 1991.

She lived in the comfort of her Canadian home for more than a decade before Roshan, 21, knew it was time for her to go home.

“I saw poor, hurt Afghan children on TV and I thought ‘I was one of those kids,’ so I just couldn’t rest.”

Roshan found the World Food Program on the internet and won the chance to go to Afghanistan as an aid worker in the summer of 2002 after pleading her case with the organization. Most aid organizations only send monetary donations, because Afghanistan is categorized as an unsafe country for aid workers. If aid workers are sent, they are interrogated to ensure that they are not involved in any schemes.

“I left for Afghanistan right when my exams were done. I felt really restless because I knew there was so much to do.” Roshan bought her ticket and booked her visa, without the permission of her parents. “My dad wasn’t letting me go and my mom was afraid because we lost a lot of family in the Soviet-Afghan war. But this is what I wanted to do, even if I lost my hand, this is what I wanted to do.”

Roshan travelled to Pakistan, then crossed the border to Afghanistan. Although there are airports in the country, it is very dangerous to fly into the capital, because planes are usually hit. “They think they’re American warplanes so they hit them and bring them down,” Roshan explains.

Crossing the border is easy — it’s getting out that’s the problem.

Pakistan wants people to go back into Afghanistan, because there are so many Afghan refugees living in Pakistan.

“The border would make you cry,” Roshan says. “These Afghans have nothing left in their country and they’re trying to escape and they are trying to find opportunities in another country but they’re getting beaten.”

Most elderly people are allowed to go back and forth between the two countries because they need medical help. Women have to have a male represent them, even if it just a young boy.

Even with a Canadian passport and visa, Roshan waited at the Afghan border for hours.

Roshan travelled across eastern Afghanistan, delivering toys and school supplies to children. She also distributed cookies that were donated from India to the children she met.

When Roshan returned to Afghanistan in May 2003, she felt like there was something more she could do for its citizens. And she was right.

“As a young girl I gave hope to all of the little girls I met. I speak their language and I am Afghan just like them — but I have an education, opportunities, hopes and dreams. I was like a light in their lives.”

Roshan wasn’t afraid of getting sick, even though she was at risk of contracting an illness.

“This is what these people live with every day. It wasn’t going to stop me from doing my work.” Roshan got lice from playing with the children, reading to them and sitting them in her lap.

She smiles fondly as she describes some of the children she met.

One girl was completely burned and she had no eyebrows. Parts of her face were melted from the leaking gas she had used to light a lantern.

“She was so beautiful to me. I said to her ‘Do you know you are so beautiful?’ and she said ‘Yes’. Her name was Narzia. I always remembered their names so they felt special.”

Her group of aid workers began their trip in the countryside, because it is often ignored by other organizations who think it is not safe there.

“There is a lot of work to be done. I didn’t go to Afghanistan to work in the city; I wanted to work in the country. There is much more help needed in the country, because there are more kids in the country. There are lots of orphans and people have bigger families.”

Roshan helped finish building a school, but there were no desks, very few rugs and only one chalkboard. The classes ranged from six to 12-year-olds, all taught at the same time.

There is a huge age gap in schools because children missed five or more years of school when the Taliban came to power in 1996.

Children’s education was interrupted, women had to cover themselves up completely — something they hadn’t done before — and men had to have beards.

“now, the men who have beards are called Taliban!” Roshan laughs.

When Roshan returned to Afghanistan for the first time with the World Food Program in 2001, she had to cover herself completely. Everything but her eyes was forced under the cover of a burqua.

But times have changed since then and she is happy to report that she only had to wear a light scarf over her hair this year. “That shows that we are making progress, and things are going back to the way they were before the Taliban.”

People aren’t forced to cover themselves anymore, but most do, including CNN reporters. “They cover their hair to respect our culture, and to be safe in case there are any extremists around,” Roshan says.

The country, she says, is slowly recovering from decades of war.

“Walking down the streets of Kabul is really strange because on one side of the streets there are destroyed, war-torn structures. You can even see bullet holes in the buildings. On the other side of the street there is construction, and new, beautiful buildings.”

The new, beautiful buildings belong to others, such as the Americans, French and Germans. Many Afghans think foreigners feel they are superior to the nationals. Fights and grudges start when foreigners put their own flags up.

“It feels like they are invading,” Roshan says.

There are soldiers everywhere. “You feel like you are being watched. You don’t feel free in your own country,” Roshan says.

She feels there is no privacy in her homeland anymore. People are being watched by their own government.

Another problem in Kabul is the roads. When the Americans bombed Afghanistan, mountains were hit hard, causing stones and boulders to fall on the roads in and out of Kabul.

“There are always old men on the streets trying to fix it once again. It’s like they are back to square one,” Roshan says.

Rebuilding efforts are carried out either by old men or young children. Because of the ongoing war, an entire generation of young men has been wiped out, leaving a huge population of women and children.

But many young women die every day as well. Roshan quietly tells the tale of a 12-year-old girl who died trying to get clean water.

“She was trying to get water out from a water pump, and it has a wheel that spins really fast. She was leaning down and her scarf got caught in the wheel and that’s it. Her hair went with it and so did her head.”

This is a huge safety issue because the pumps are not protected, but there is nothing the Afghans can do about it. “Whether you knew her or now, you were crying. Her family was screaming.”

The trip back to her homeland taught Roshan a lesson about Western and Eastern culture.

“I appreciate everything now that I’m back. I try not to spend money on crap anymore and take advantage of the opportunities,” says Roshan. “But the nicest thing is that everyone was happy in Afghanistan, more than here. They have family values and culture. Somehow, they found happiness.”

Leave a Reply