By Rebecca Burton

Karyn Elliot and her friends crowded around their made-up bingo cards.

They weren’t waiting for a B5. Instead she was waiting to hear one of the five topics her professor constantly ranted about in class, she says.

The prof begins to talk about how humans are evil. “Bingo!”

Elliot, a second-year radio and television arts student, sat through this communication class for 13 weeks last semester. During the semester, the class watched a threehour movie the professor made his ex-girlfriend watch the night before, and learnt about the enslavement of horses.

“He just expressed his own opinion. It’s understandable because most professors do but usually it connects back to the course,” she said.

“I learned nothing in that class.”

Elliot submitted a mandatory response paragraph after every class saying the class was pointless. She created an anonymous hotmail account and sent two e-mails about his teaching to her department head. She even filled out the faculty course survey. Elliot never heard back about her complaints.

According to Elliot, the professor dismissed the complaints by students saying it didn’t matter what they thought, it’s what he taught.

Elliot is part of only one quarter of students who give feedback to faculty professors through surveys.

And even when there is an extremely negative response from students, it is nearly impossible to dismiss tenured professors, according to John Isbister, Vice Provost Faculty Affairs.

Ryerson University prides itself on being a unique real-world oriented university, but the once polytechnic institute is still haunted by the persistent ‘Rye High’ nickname. And when students question the quality of their education they have no clear avenue to judge how it ranks.

Is it possible to measure the level of education at Ryerson?

“The true answer is no. It’s so individualized,” said Isbister. Instead, Ryerson measures the quality of education through surveys like the faculty course survey produced on a yearly basis.

According to the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada, most schools rely solely on these annual student surveys to judge the satisfaction of their students.

Now in its 18th year as an accredited university, Ryerson has developed from a small institute born to provide an alternative to apprenticeship technical training into a booming hub of 28,000 students in more than 40 programs. The province officially accredited Ryerson in 1993 when a bill was passed to grant them official status.

As a university, Ryerson moderates its own academic success. The provincial Ministry of Universities and Colleges acts as an overseer — looking at the accountability of Ryerson to assist them in development and to aid prospective students.

In their assessment, they look at employment rates at six months and two years after graduation, degree completion rates and Ontario Student Loan default rates.

And Ryerson on paper ranks high. In the past few years, Ryerson experienced some of the highest application numbers, approximately 65 000 applicants for the 5 000 available spots.

Within six months an architecture graduate is 92.3 per cent likely to already be working. Compare this to neighbouring University of Toronto that holds the historical esteem and a greater selection of programs, and Ryerson is almost on par with their 100 per cent average of obtaining a job after completing the architecture program.

“We’re the best of what we are. We don’t try to compete because of what we are,” said Adam Kahan, Vice President of University Advancement. “We’re a different institution,” he said.

But problems arise when Ryerson relies solely on the faculty course survey as one of the key indicators of success.

Of the small population of students that completed the faculty course survey in fall of 2010, most marks remained in the high average of 1 to 2.4 out of 5, indicating most students agreed with the statements presented.

The survey included 14 questions such as, ‘is the instructor knowledgeable about the course material?’

Anver Saloojee, head of the Ryerson Faculty Association, who holds a tenure professor position in the department of politics, received an average score of 1.1 to 1.2. A reasonably high average, he said.

But this data remains very department oriented. If bad results come in, it is dealt with internally between the faculty member and the department. If that professor is tenure it becomes nearly impossible to dismiss them, according to John Isbister.

Along with their secured position they are granted academic freedom, a problem Elliot says she faced during her many misguided lectures.

“Individual data is not released and that’s the problem. The benefits are very individual. For instance, students can’t use this [data] in picking courses,” said Isbister.

Instead he said students would have to rely on alternatives such as ratemyprofessor. com, which offer the same student driven perspective.

The surveys also aid in the departmental decisions over choosing to promote a teacher. Close attention is paid to a teacher’s first five years when they are on probation in which they must submit reports every year.

“Ryerson doesn’t want to make a lifetime commitment to someone who’s not a good teacher,” said Isbister.

The idea of tenure is controversial in itself, according to Isbister.

But if Ryerson chooses, after five years probation and a number of peer to peer evaluations, to grant a teacher tenure the professor will be given academic freedom.

The main purpose of tenure, indicating a professors full time status, is to ensure professors will not be fired for expressing his or her own opinions. But this also grants a lot of leeway from the outlined course materials.

In another survey Ryerson participates called the National Survey of Student Engagement, more disturbing scores, according to Isbister, indicated that as a student went further along in their education the scores for student engagement on campus and fulfillment of their programs dropped.

As a result, Isbister said Ryerson will be undergoing a whole curriculum redesign to offer more choice for students.

“We tell you what courses to take. We’re beginning to think we’re too directive,” he said.

According to Isbister, students will still leave Ryerson as a professional but their four years will grant them more avenues to explore what they personally want to study.

“There will still be less choice than strictly liberal arts universities but we may have gone overboard,” said Isbister.

“We’re not in agreements yet but we’re working on it.”

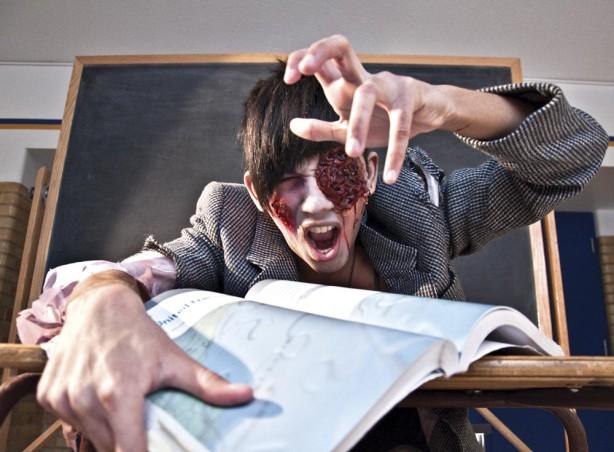

Photo: Marta Iwanek

Leave a Reply