By Sean Wetselaar

On Jan. 25, 2011, a huge assembly of students invaded one of Ryerson University’s regularly held senate meetings. Representatives of the Ryerson Students’ Union (RSU), including board and executive members, along with regular students and media had assembled to watch the final motion of a policy change that would give students a fall reading week to complement the winter one.

This motion came after numerous failed attempts by students to create a fall reading week. After a chance for students to debate it, both in favour and against, Ryerson President Sheldon Levy called a vote.

“I remember distinctly sitting at the side there and then the motion came up,” says RSU President Rodney Diverlus, then in his first term as vice president equity. “And the vote happened. It passed. We freaked out.”

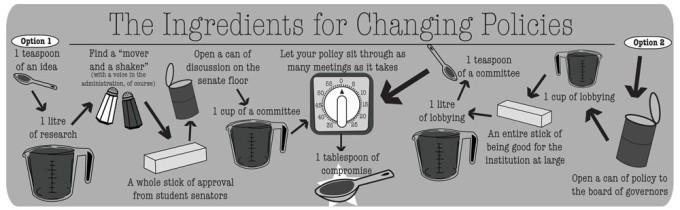

Ryerson policy is a dense, complicated affair, and changing it can be more dense and even more complicated. But, when it comes down to it, lobbying the university for policy change is, in many regards, the best bet a student has at making a direct impact on the university and how it does business.

The first step in pushing a policy change forward, says Levy, is to identify whether the policy in question is academic or nonacademic, meaning policy to do with the administration.

All policy at Ryerson must be passed by a governing body; the senate for all academic policy, and the Board of Governors for all non-academic policy.

However, Levy cautions that the school does not take policy change lightly.

“Not only do you have the responsibility as a student to be able to take opportunity to change policy, you have to be able to do your homework as well,” Levy says. “I hope that a university wouldn’t change policy whimsically and would require a good deal of thought and a lot of care, and a lot of research before changing university policy. I think that’s an absolute necessity.”

Due to the amount of research done in advance, the RSU, then under the reigns of former president Caitlin Smith, managed to once again push the issue of the fall reading week forward, despite the senate having previously turned it down.

Preparation included a campus-wide survey, a motion at the semi-annual general meeting, election platforms, and lobby meetings with the registrar’s office and the school’s many faculties.

“It’s a big beast – keep figuring out where to poke it,” Diverlus says. “But you try different tactics and you escalate them until you can get what you want. But if we’re told ‘no,’ we take the ‘no’ not as a barrier but as ‘challenge accepted.'”

Another factor, Diverlus says, was involvement of the student senators in the process from the moment the students decided to push the proposal forward, to the moment it was “served,” or presented to the senate.

“As with any change to the university, you want to make sure you’re consulting all the stakeholders,” says Melissa Palermo, vice president education with the RSU.

Another important step in changing policy is finding the right people in the administration to back your cause. One frequently consulted candidate for this role is Heather Lane Vetere, vice provost students at Ryerson.

Vetere says that she often has students come forward with complaints that go to local policy in individual departments, but that she is also involved in bigger issues such as the implementation of the fall reading week.

“I’ve only been at Ryerson for four and a half years, but [my] entire career has been in this field,” Vetere says. “I’ve only ever worked with students … I couldn’t do this job if I didn’t enjoy working with students.”

Once a policy is opened to debate, by administration or a majority vote, a committee is struck, comprised of student representatives and any other groups that will be affected by the policy change, often including the office of the registrar and faculty representatives.

It is the job of this committee to create a recommendation that will then be passed on to either the Board of Governors or the senate.

Despite initial concerns by the faculty of community services, Diverlus says, a compromise that allowed students to still get their placement hours brought them on-side.

But, engineering students continued to be concerned with finalizing their degrees through accreditation, which would be voided by the reading week. Diverlus knew that the engineers would not support the proposal as it was, and that without their support it would not pass in senate.

“The issue of engineering was something we couldn’t wrap our heads around,” Diverlus says.

Eventually, engineers were persuaded to agree to the fall break on the condition that they would be allowed to opt out.

Only one barrier stood between the students and success – the final senate vote.

When a committee has come to a universal agreement on the manner in which policy should be changed, it passes to a final majority vote after analysis by both the president’s office and Ryerson’s legal department.

For both Diverlus and Palermo, the final meeting was the moment to bring everything they had to the table.

“You present all the arguments, and it was all of your ammunition out because it was like, ‘You can’t say no to this,'” Diverlus says.

Changing Ryerson’s policy is not easy. It sometimes takes years of research and lobbying, and requires an in-depth knowledge of Ryerson’s bureaucracy and chain of command.

It can be an exercise in strategic influence of the administration, or mass petitioning of students.

But to give Ryerson students a legitimate chance to influence policy is, as Vetere put it, “an amazing, amazing opportunity for students, in building their own leadership skills.” And the simple truth is that no matter how much work can go into policy change, if you don’t like something, there’s no excuse not to change it.

Leave a Reply