By Dylan Freeman-Grist

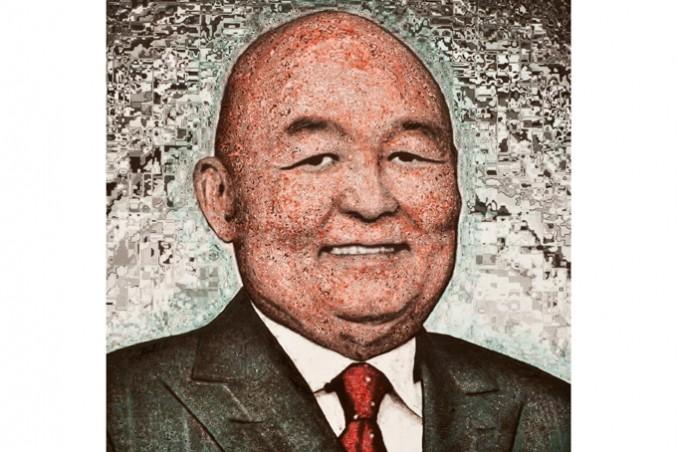

On a hushed stage facing Ryerson’s graduating class, Raymond Chang stood in front of the departing seniors. Dressed in a robe of blue and gold, he gazed over the crowd.

He was a millionaire, a successful business man and a renowned philanthropist but ask anyone who knew him and they would tell you that it was here, on this campus, he was most at home. Ryerson students were his passion and of all the passions in his life, and there were many, education was near the top.

Beaming with his signature smile, he began what would be his final speech to a hall filled with the class of 2012.

Chang, who would become Ryerson’s third chancellor, was born Nov. 24, 1948 in Kingston, Jamaica.

He was the third of seven children and lived on the same street as his family and cousins (35 in total) in Kingston. He assisted his mother in running one of the largest bakeries in Jamaica, which peddled fruitcake across the island.

Chang went on to immigrate to Toronto, where he became a millionaire on Bay Street and a well-known champion of philanthropy in both Canada and Jamaica. Later in his life, when he came to the school, he was often referred to as the “Students’ Chancellor” of Ryerson.

Chang died on July 27, after a battle with leukaemia. He was 65.

In 1967 Chang left Jamaica for Troy, N.Y. before settling in Toronto shortly after to study engineering and commerce at the University of Toronto.

He went on to complete his chartered accounting designation before earning a fortune on Bay Street while helping to morph a then-tiny investment firm into current juggernaut CI Financial. In the most recent financial quarter, CI’s total assets topped $128-billion.

“I always thought of Ray as someone who thought the highlight of his career was the six years he spent at Ryerson,” said Bill Holland, a longtime business partner at CI and close friend of Chang. “As much as he was a huge success in business his real passion was education.”

Chang’s tenure as chancellor began in 2006 and ran until 2012.

While the title of chancellor can often be simply ceremonial in nature, Chang’s life-long passion for education culminated in his office and manifested in his actions.

“I would say that in any university a chancellor is an important figure representing the values of the university and Raymond did that extremely, extremely well,” said Ryerson President and Vice-Chancellor Sheldon Levy, who worked with Chang for all six years of his tenure. “He was someone who really generally loved students.”

That love took many forms, with perhaps the most notable being the philanthropic activity Chang brought to the campus. He poured millions of his own dollars into helping to develop and build Ryerson into the institution it is today.

Publicly, Ryerson discloses that Chang donated five-million dollars. But he had a tendency to request anonymity when he gave back, so the figure could be much larger. Either way, the G. Raymond Chang School of Continuing Education today carries his name because of his generosity.

Marie Bountrogianni first met Chang when she worked at the Royal Ontario Museum. She stayed there from 2007 to 2011 as president and executive director.

She recalls pitching the idea of making the Toronto landmark the most accessible museum for those with disabilities in the country.

Chang put up the money instantly, funding ramp and incline renovations and the development of miniatures to allow the blind to interact through touch with exhibits blocked by glass. It also funded staff and training for special walking tours — the list goes on.

“For six months I couldn’t tell anyone either, I couldn’t tell anyone he gave us the money,” Bountrogianni said.

Now dean of the Chang school, she recalls his same zeal for helping where he could right here on campus.

One major project he backed was an initiative by the Chang school to support and maintain an online continuing-education nursing program for students in the West Indies.

The program has helped to train over 400 nurses in nations such as Jamaica, St. Lucia and Belize.

“This had tremendous impact on the healthcare in the West Indies, they have a nursing shortage,” Bountrogianni said.

The nursing program is now offered to students across Canada.

On the corner of Yonge-Dundas Square, a bustling office looks out onto one of Canada’s busiest intersections. Huddled on the sixth floor is Ryerson’s Digital Media Zone.

Apple computers and messy desks are a signature of the entrepreneurship incubator, the number one university-affiliated startup centre in Canada and the fifth in the world.

Employees and entrepreneurs, many of them Ryerson students, dash wildly from meeting to meeting or tinker for hours on the next great analytic service, social media platform or smartphone app.

Millions of dollars have been developed in revenue, most of it enhanced or supported by students in some capacity.

This whole operation was made possible by Chang, who put up money to speed the process when the DMZ was just an idea being tossed around Ryerson board rooms.

“There were many occasions where a student would need some funding for a project and I would talk to Raymond,” Levy said. “I’d say, ‘Ray I just met a student,’ [and] immediately he would have a big smile on his face and be willing to support them.”

Levy recalled a time when Chang simply called him to say he’d be giving half a million dollars for any student projects the administration wanted to support.

Chang sat, looking on intently as a group of students mulled over the details of a classical revamp of an Antony and Cleopatra script. He was sitting in on a performance acting class. Though he may have been one of Ryerson’s most generous donors, his dedication to the school transcended his chequebook.

“How many chancellors show up at the school every single day?” Holland said. “He went to the classes because he wanted to know the students’ experience, he wanted to know the teachers’ experience, he wanted to understand the quality of teaching.”

Chang would spend extraordinary amounts of time in Ryerson’s classrooms, like this one, learning from students. His choice of lecture was in no way tied to his own academic background.

While students ran through their lines and motions Chang did not stir, remaining in his seat to ensure he saw the class through.

“It was nice because some people just do it to make an appearance but he’d stay for hours,” said Cynthia Ashperger, an instructor at the Ryerson Theatre School who taught a handful of courses that Chang attended. “He was curious about it and I think his curiosity is what took him far in life [and] apart from his ambition, he was genuinely curious.”

A steel drum buzzed through the hall during Ryerson’s convocation. The instrument, a polished plate that is a pillar of West Indian music, was added to the ceremonies to honour and celebrate Chang’s final ceremony as chancellor.

Chang flashed his signature smile on stage before he spoke.

“We are counting on you to draw on the knowledge and skills you have gained at Ryerson — transform them into ideas and actions that bring prosperity, peace and happiness,” he said. “But whatever you do, or wherever you go, I challenge you [to] make a difference. Ryerson believes in your abilities and stands ready to help you again if further learning is in your plans.”

He stuck around after the ceremony, as he often did, ceremonial mace in hand, to pose in as many pictures with students as he could, always making sure they showed their degrees.

He believed there was nothing more important than education. To him, it was an equalizer, a building block, the first step to a bright future.

As they posed for pictures, Chang made sure to greet all the students by name, reading them off their degrees, to make a personal connection.

Two years later he was gone. Yet in his six years at Ryerson he left his mark all over the campus. His legacy, as a man who dedicated his life to propping up others, tied infinitely to Ryerson’s future.

Leave a Reply