By Jacob Dubé

Elaine Wilson was wrapping gifts in front of the TV in her home on McGill Street when she heard something outside. It was just after 9 p.m. on Dec. 15, she had just come home from work and it was too dark to see anything. About an hour later, she looked out of her bedroom window and saw police tape tied to a tree in her front yard. Toronto police were on the scene, and she heard that somebody had been stabbed.

Her close friends, Robert Iseman and Mark Ernsting, lived just a street away, so she sent them a text letting them know about the stabbing. Iseman called her right back to tell her that Ernsting, his husband of five years, had not come home from his nightly walk.

Worried, she approached a cop on the street to find out if they had seen the victim.

“He doesn’t look like he’s doing too good,” the officer said.

When she asked about Ernsting, the officer told her that he could have been a witness to the stabbing, and in that case he would have been taken to the precinct for questioning, unable to use his phone.

Wilson called Iseman back and he met her near the scene. Together, they approached another officer and told them they were getting worried.

“Okay, we’re concerned here. My friend, and my friend’s husband here, he’s not home, and he’s never home this late,” Wilson recalls saying.

The cop told them to go home and wait, that they would be okay.

They were waiting at Wilson’s home when they found out the victim had succumbed to injuries in the hospital. It was around this time that Iseman found Mark’s wallet, along with all of his identification, in his bag. He hadn’t taken it with him on his walk.

Wilson and Iseman spoke to a third officer to say that they wanted to go to the precinct, speak to the witnesses and see if Mark was with them. The officer began questioning them about him. They matched his name to his driver’s license photo — confirming that it was Mark Ernsting who had died.

“It was easily the worst moment of my life,” Wilson admits.

“It was easily the worst moment of my life.”

According to Toronto police, Ernsting was on his nightly walk on McGill Street when a man approached him, attempted to rob him and stabbed him.

He was 39. He was a biomedical engineer and an adjunct-professor at Ryerson University. He’d been married to Iseman for five years, but they had been together for 10. Wilson had met him soon after she moved to Toronto — they had been friends for over 15 years. She started calling him Wendell, referencing the nauseous Simpsons character, after he laughed so hard at a joke once that he threw up. He died on Dec. 15.

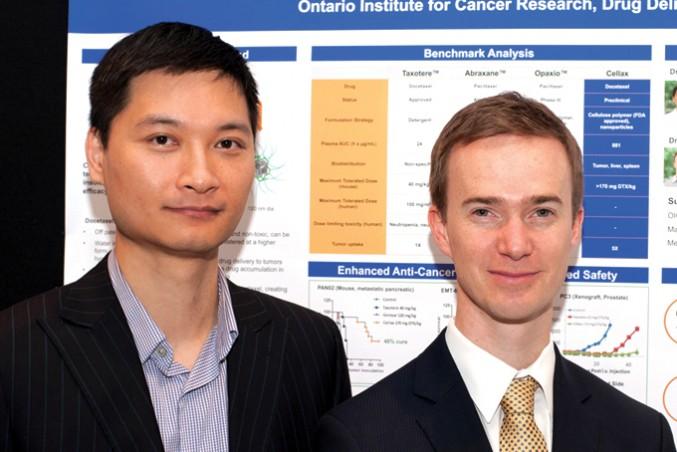

Ernsting worked for the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR) as a biomedical engineer, while also serving as an adjunct professor in the faculty of engineering and architectural science at Ryerson.

He was working on a drug delivery system, smaller than a red blood cell, which would release if subjected to a certain temperature. Practically, it could be used to target the release of chemotherapy drugs exclusively in a tumour, which would minimize the infamous side effects.

“When you do get cancer, your immune system is already weakened. Attacking it with more drugs does nothing but weaken it further. So that does play a huge role in the outcome of these patients,” says Eno Hysi, a graduate student in biomedical physics at Ryerson. “Even though they might be cured of their cancer, they’re still sick because of the effects of chemotherapy.”

Hysi says that the research he’s doing now wouldn’t be possible without Ernsting’s contributions to the invention.

“He was a great guy. We would work very late in the lab at night, and he would always offer to give us a hand if we had any difficulties,” he says. “It’s going to be a big gap to fill. Not just because he was a great guy, but because he was a brilliant researcher.”

Ernsting’s death came as a huge shock to Hysi, who passes by McGill Street several times a day. “You hear about robberies, but not robberies gone wrong.”

The accused, 21-year-old Calvin Michael Nimoh, was arrested within an hour of the incident and has been charged with first-degree murder. According to homicide Det. Paul Worden, the charge was upgraded from second-degree to first on Jan. 7, after evidence of forceful confinement was found. According to the CBC, Nimoh was also charged with robbery, assault with a weapon and carrying weapons dangerous to the public peace, in relation to another violent robbery earlier that night.

Shyh-Dar Li worked with Ernsting at the OICR since 2009. Their relationship began while Ernsting completed his training at the OICR for two years, then decided to stay with the institute — despite receiving other job offers. Together, they co-invented the chemotherapy delivery system.

Around the time when Li’s daughter was six-months-old, he held a party at his home. He says that she was beginning to recognize people, and became more selective about who she would let near her. Amazingly, he says, she was always drawn to Mark.

Just a day before Ernsting died, the two were still exchanging emails about their research. Ernsting sent Li a couple of questions on Monday, but he wasn’t able to respond before he heard the news of Mark’s death on Wednesday.

“That’s really shocking, because I remember Mark told us how safe Toronto was,” Li says, explaining that he moved to Toronto from the United States. “We were always wondering how safe the city was, and can we feel safe walking on the streets at night. And Mark was always very positive.”

Li had a friend in the United States who also died after a robbery two years ago. Since the events of Dec. 15, Li double-checks his doors every night to make sure that they’re locked. “I never thought this would happen again to my friend.”

Li says Mark’s dream was to get their invention to the stage of clinical trials. The OICR is taking over with the project.

“I hope he knew how much I appreciated working with him,” he says.

“I hope he knew how much I appreciated working with him.”

On their last annual camping trip, when Wilson and a friend arrived to the site, Ernsting was already there, alone, and the entire campsite had been set up. All that was left was wine and dinner.

“He was a MacGyver and a boy scout. This guy didn’t have a lazy bone in his body,” Wilson recalls. “It was like a 12-man tent. He just said he needed help putting the fly on.”

Along with the camping trips, Ernsting often went mountain climbing with his husband.

“He was like zero per cent body fat and in the prime of his life when this happened. Very healthy guy,” Wilson says. “He maybe drank wine, but other than that, clean guy. I always said I would die before this guy.

His mountain climbing skills came in use one day when Wilson had to move her bedframe up to her third-floor apartment. He attached the frame to climbing ropes and hoisted it up from the outside. “If it weren’t for him, I’d be sleeping on a mattress on the floor,” she says.

Even when they had nothing planned, Ernsting, Iseman and Wilson would meet up once a week to cook a gourmet dinner together. Wilson said that the couple would do everything in their power so she wouldn’t feel like a third wheel.

“There was no hiding it. They were both crazy about each other,” she said. “I know Rob is going crazy without him. If Mark went on a short business trip, Rob would go a little crazy and invite me over, in lieu of Wendell. They would even Skype. They were a really, really, really adorable couple.”

One morning, Wilson was making a sandwich, preparing for work, when she cut her hand open. She was home alone. She called Ernsting and in no more than 60 seconds, he was there.

“You’re a doctor,” she said. “Tell me how bad it’s going to be.”

“You’re fine. Did you give blood in high school?” Ernsting asked her. She said yes. “That was a bag of blood. You really haven’t lost that much.”

He took her to the hospital, where he stayed with her.

“I know it’s things that friends and neighbours do but we were very close, like family,” Wilson says. “We talked about getting old and looking after each other, and when that happens. We were like family, here, together.”

Leave a Reply