By Julia Nowicki

For Greg Hannon*, it was a brotherhood, a bonding experience. During his time working in the restaurant industry, Hannon had used practically every drug under the sun.

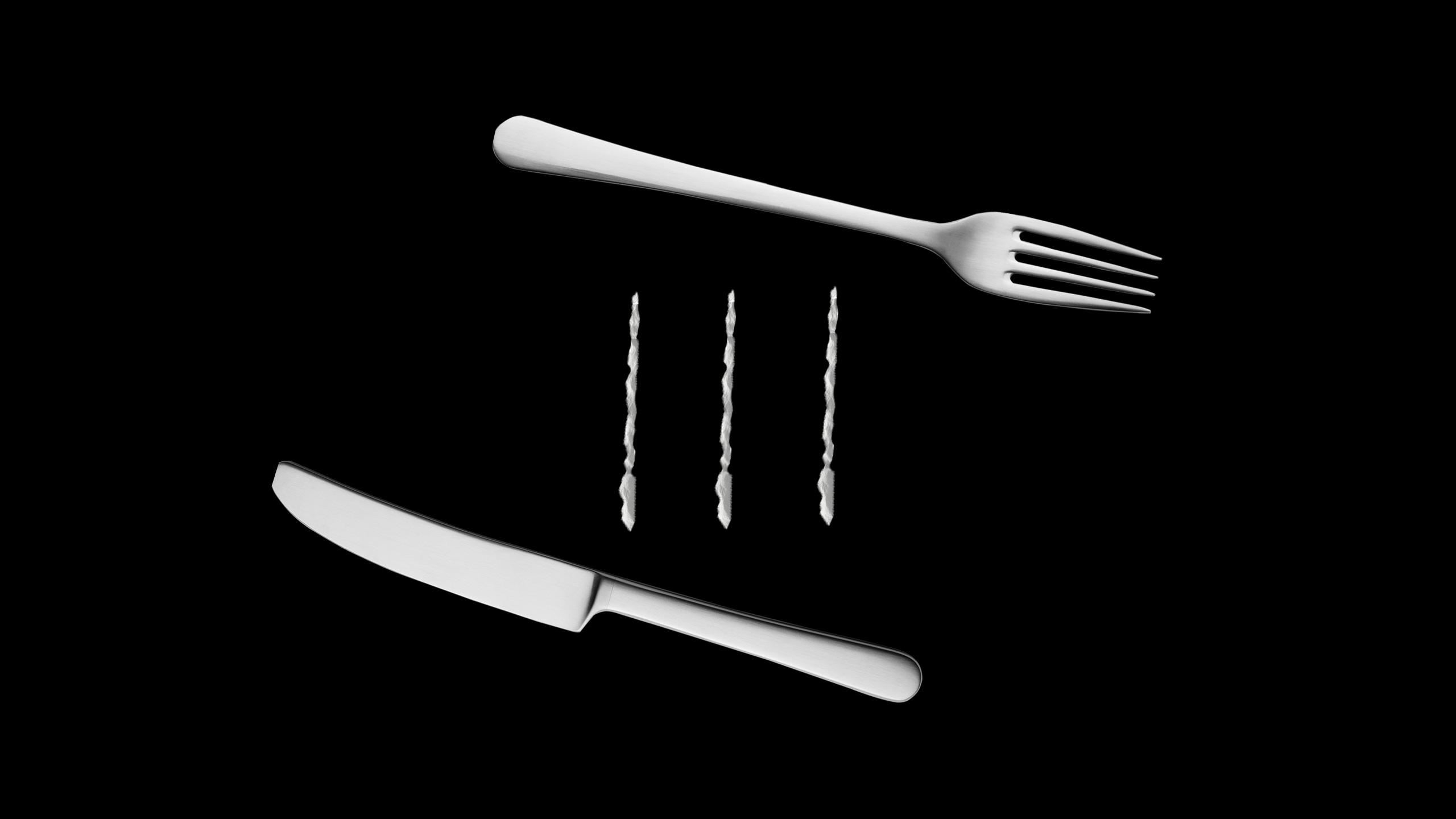

Cocaine was new to him. He was hanging out with a couple of co-workers from Jack Astor’s, a place that he had only been at for four months at the time. The staff used drugs often, and it was normal for them to head to the bar or someone’s house to relax after a long shift. Two of Hannon’s friends stood in his kitchen winding down on a particularly busy night. After a 12-hour shift, it’s hard to relax and Hannon’s head was still buzzing from the adrenaline in his body. His friend eventually pulled out a small bag of cocaine and began arranging the white powder into white lines on his kitchen island with a credit card.

Cocaine was normal for all of them, but not to Hannon. He used to think that doing and acquiring cocaine was as dramatic as the scenes he saw on TV—with guns and backstreet deals—but here it was, being spread on his counter like it was nothing. Hannon usually declined when the five-dollar bill was passed to him, but this time curiosity got the best of him. After he snorted two or three lines, the subtle effects began to take hold. He felt light-headed and the music playing in the background sounded louder. Things started moving in slow motion around him. That night the three became closer as friends and colleagues. After all, it was a bonding experience.

Hannon, currently a Ryerson student in his first year of the public health program, worked as a cook for about nine months. He was quickly exposed to the drug culture that existed among his co-workers.

But the prevalence of drug and alcohol use amongst restaurant workers is shockingly higher than any other industry. Stress, harassment, long hours and the general permissive attitude that exists around drug and alcohol use in the workplace are significant factors that contribute to such high numbers.

In 2013, Statistics Canada released a Canadian Community Health Survey that included questions related to workplace stress. According to the survey**, 28.1 per cent of workers in the restaurant industry had reported using illicit drugs, compared to all other industries sitting at 17.6 per cent on average. Incidence of smoking was also markedly higher, resting at 22 per cent compared to the general average of around 16 per cent in other industries.

Kelly McShane, an associate psychology professor at Ryerson, received her PhD from Concordia University in clinical psychology and has experience in researching addictions.

I guess there is an unwritten rule amongst co-workers, if you known someone is in on it you don’t say anything about it

She maintains that, although many workplace factors contribute to a higher overall tendency toward stress and subsequent drug use during and after work, the overall workplace dynamic prevalent in the restaurant industry contributed greatly to such a high incidence of drug and substance use among workers.

“What no one really talks about is the cultural component, access and presence of alcohol and drugs. Particularly cocaine and alcohol in the food and beverage industry is very high,” said McShane. “It’s available and everybody is doing it. It’s a classic cultural thing, the peer pressure.”

Hannon said that some staff would party almost every weekend after their shifts. After his first time actually partaking in using cocaine, Hannon began to see it happening at work as well. He would walk into the bathroom and notice white dust on the toilet dispensers, while some of his staff would act uncharacteristically happy and energetic.

“Now that I knew how normal of an activity it was, I didn’t really think of it twice. I guess there is an unwritten rule amongst co-workers, if you know someone is on it you don’t say anything about it,” Hannon said. “Looking back at it now I kind of realize how abnormal it is.”

Peer pressure is only one of the factors that contribute to ongoing drug abuse in the restaurant industry. Management’s concern toward alcohol and other substance use on the premises can be lax and ineffective at controlling those behaviours, said McShane.

“We know from a preventative stand-point, if workplaces don’t have policies around not drinking on the job or around successful interventions and EAPs (Employee Assistant Programs), we know that puts workers at risk,” McShane said. “I think there is high stress, coupled with availability and long work hours, and the lack of oversight, whether it be managers or owners.”

Hannon said that the pressure to bond with his co-workers contributed to his brief history with cocaine use.

“It kind of enabled it,” Hannon said. “You know other people are doing it and they still wake up in the morning. You don’t want to be the one that’s being left out.”

It was around 9:00 p.m. on a Tuesday. Lindsay Fairlie* stood at the sink washing dishes at the Fionn MacCool’s she worked at part-time. She was a high school student and worked any job that they would give her in the kitchen. There was a late rush and she knew she would be at work longer than she had previously anticipated.

As her two co-workers, James* and Thomas*, were leaving to go for a smoke break; they called her over. She stopped her work and joined them as they left through the back and piled into James’ car. They each pulled out a joint and turned on some music. Smoking weed during a shift was common for the two. Thomas dealt weed from behind the fuel filler door of his car, with payments made by slipping bills into his open window. James was in charge of the harder stuff, the non-medicinal substances like cocaine. Fairlie sat in the back seat, listening to the conversation between the guys and the trap music playing in the background.

The two were talking about some strip club they were at the night before. James turned to Fairlie and handed her the joint. Normally she would say no, but this time she took it without a thought. Eventually the three left the car, sprayed some Axe, and headed back into the kitchen.

It had been almost two years that Fairlie had been working at the restraurant and it was the summer before she started school at Ryerson University in the English program. She had quit smoking weed and taking other drugs before starting at the restaurant in September 2015, but eventually took it up again when she was made aware of the drug use going on among staff.

She said at one point she walked in on a cocaine deal being made between a former employee and a cook at the back of the kitchen. After she promised to keep it a secret, the rest of the staff began to trust her and use her as a confidante and look-out for deals being made during open hours. After work the staff would head to the nearest pub that served under-aged people and do more of the same.

Although Fairlie maintains that social influence was the main factor in drug use among the staff, the physical and psychological demands of the workplace contributed to her using certain drugs like Xanax and weed at work to relieve stress.

“The environment got really stressful, and since you’re at the bottom of command, people would yell for unreasonable things at you, stuff you can’t control,” Fairlie said. “In a heightened environment like that sometimes you need to pop a Xanax and calm the fuck down.”

Darren Clay is the executive culinary chef instructor of the Pacific Institute of Culinary Arts in British Columbia and is part of the Chefs’ Table Society of British Columbia.

He said that the industry as a whole is looking toward starting a conversation about mental health and stress in the workplace. With the new generation of cooks and chefs coming in, they see the long hours and low pay and are turning away from the industry or forcing widespread changes.

“There is a whole new generation of chefs and executive chefs that are changing that mold. They are trying to have a little more balance for their chefs and their cooks,” Clay said. “What we are dealing with in our industry is a lot more mental health issues and they’re trying to bring that to the forefront and trying to get people to talk about it because of all the stress (they experience).”

Although Fairlie still drinks and smokes weed on occasion, she says that she has taken measures to deal with her stress properly since leaving Fionn MacCool’s. She actively tries to surround herself with people that promote a different lifestyle.

“When I have stress, I ground myself and call people instead of partying it off or taking a smoke,” Fairlie said via Facebook.

However, Clay maintains that a broader shift may have to occur in the industry to deal with the labour shortage currently troubling many businesses and restaurants.

“I applaud them for drawing a line in the sand and saying ‘we’re not going to do what used to be done, we’re not going to work 14 hours a day six days a week,’” Clay said. “That’s where restaurateurs and chefs are having to rethink their ways to retain staff.”

*Names have been changed.

**You can find more of this data in the following study: “Au menu : ma santé mentale, La santé mentale des travailleurs et travailleuses de la restauration: test du modèle demande-contrôle-soutien de Karasek et Theorell,” by Samantha Vila Masse

Leave a Reply