It’s well known you have to have money to be part of sport programs growing up. But the financial barriers have led to low-income and immigrant families feeling particularly excluded

By Madi Wong

Illustration by Jimmy Kwan

Growing up, Derrick Allahyarian developed his basketball skills at his elementary schools’ parks and by playing house league. He had a passion for playing and following the demeanours and buzzer-beaters of his favourite player Kobe Bryant, which he incorporated into his own style on the court.

Allahyarian, a business management grad, was elated when he made his first school basketball team in Grade 7. But in Grade 9, when he joined his high school’s junior basketball team, Allahyarian began to develop a different attitude as an athlete. Because he didn’t have the same opportunity to learn fundamental skills from being enrolled in sports programs, he didn’t know much about plays or drills.

“I just knew: put the ball in the net,” he says. Allahyarian recalls his then-coach calling him out for messing up a drill and mocking him by asking, “Have you not played basketball?” In response, Allahyarian mentioned he played house league and streetball, which was followed by his coach and other teammates laughing.

He says in that moment, he realized it wasn’t a common thing for kids like him to make it to certain levels by playing house league.

By university, the former business management student was able to play on the Ryerson men’s basketball team from 2012 to 2016.

But again, his experience as a Rams athlete was different from other students. He struggled while balancing a part-time job, school and commuting—all on top of committing to the school’s team. It involved waking up at 5:30 a.m. to commute, attend classes, practices and more. Sometimes he didn’t get home until 11 p.m. or later.

Before he came to Ryerson, Allahyarian grew up in a predominantly white neighbourhood in Hamilton, Ont. Though he grew up playing both soccer and basketball, he experienced the financial barriers of sports when he saw a majority of his peers playing hockey.

“As a child, [seeing] all of your friends playing hockey makes you want to play hockey and obviously, that financial barrier was there,” he says. “My parents were new to Canada, I’m a first-generation [Canadian]—so that was out of question.”

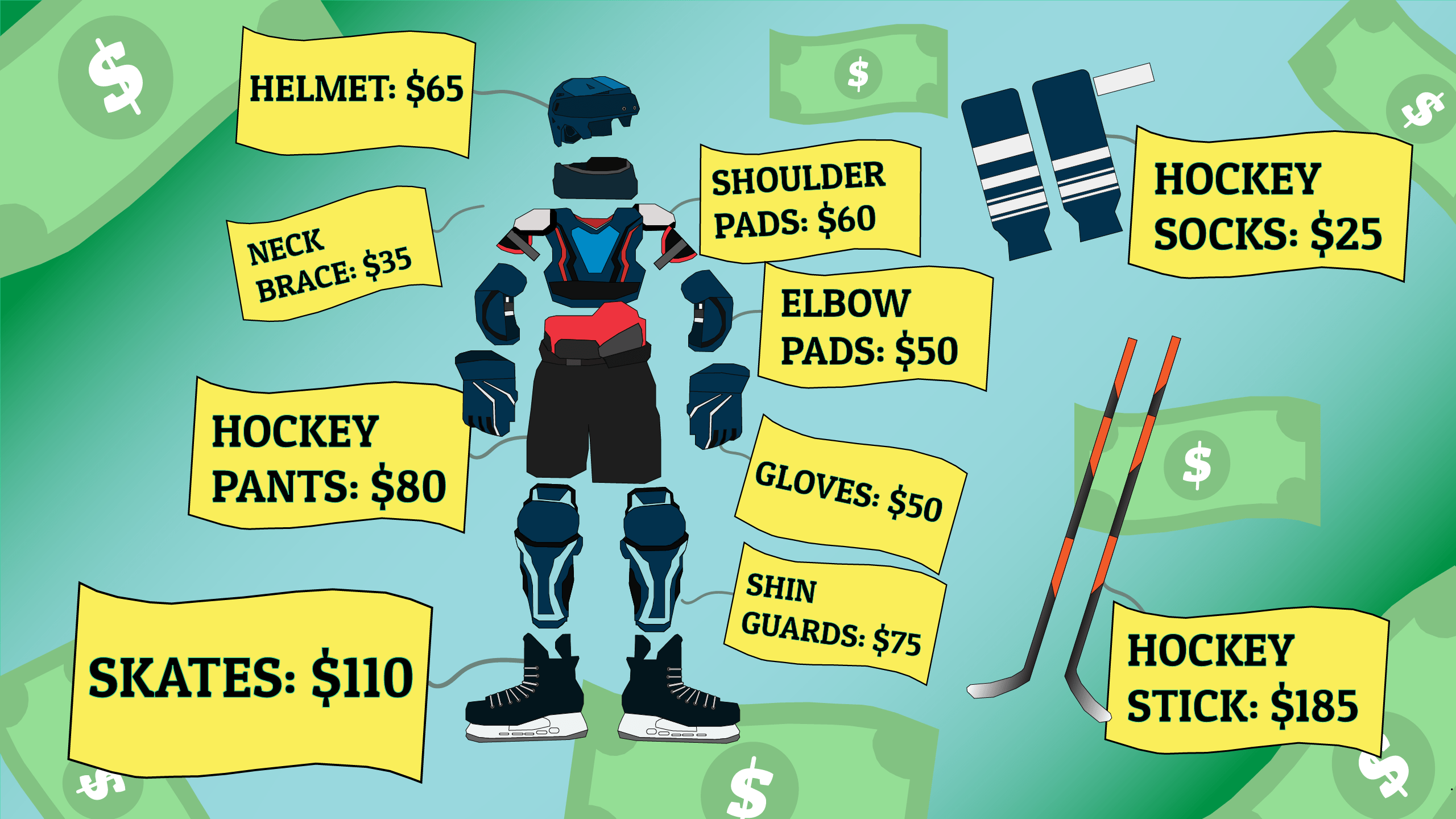

Hockey is one of the most expensive sports to play in Canada. The average cost for a child to participate amounts to almost $1,666 annually, which includes the program and other aspects such as equipment, according to a 2014 report by Canadian Youth Sports. Other cost-heavy sports include equestrian at an average of $1,434 annually and skiing at $2,028 annually.

With such high costs to access sports programs, children and youth who come from low-income—and particularly immigrant families—are often left with more barriers to overcome in order to have equal opportunity, says Nick Holt, professor in the Faculty of Kinesiology, Sport and Recreation at the University of Alberta.

Holt has been involved with multiple studies looking at the different aspects of sport participation with kids from low-income families. “Cost, travel and transportation are the primary barriers to sports in Canada because we operate on a pay-to-play model,” Holt says, who also coaches youth soccer. On top of that, as kids continue to improve and reach higher levels, prices can rise, adding to the barrier for low-income families, Holt says.

The costliness of sports has long been an accessibility issue for families trying to enrol their kids in sports programs. These barriers are so ingrained that now, athletic culture has been built with an emphasis on having money rather than being open to everyone—especially low-income kids and families.

“The majority of youth sport participants in Canada tend to come from middle class, upper-income families…usually Caucasian kids,” Holt says. He adds that being in a class with predominantly upper-middle-class kids can lead to kids struggling to feel like they belong if they don’t identify within that social group. “Similarly…if you’re the only person of colour or the only Indigenous kid on a team of 20 white kids,” he says.

iriam Jamal, a Ryerson sociology graduate, thinks addressing the inequalities for those who can’t afford sports programs is “critical.”

As a program coordinator at KidSport Ontario—a branch of an athletics association that provides resources for under-sourced families wishing to participate in sports programs—Jamal often works with families and social workers. Growing up, Jamal was exposed to programs such as swimming as a kid. But she never thought of participating in sports like gymnastics because she didn’t see it as a possibility—it seemed less financially accessible.

“I think the goal to enjoy sports are misplaced and overshadowed by the need for financial success. In our capitalistic society, sports can be driven by the idea of gaining validation,” says Jamal.

Jamal adds this validation can come from anywhere such as potential scholarships and sponsorships and gaining a fanbase.

That idea of validation can cause people to forget the importance of what sports should actually be about, she says, such as acquiring skills, learning to be a teammate and benefits to psychological and physical health.

“It is human nature to want to feel a sense of validation, so capitalism in sports can often convince one that you are a great athlete based on the more money and fame you gain in your respective sport,” she says.

When it comes to low-income and immigrant families, many are unaware of what resources are available to them such as bursaries. On top of being underprivileged financially, Jamal added that these families experience discrimination, or if you’re an immigrant family, isolation. This kind of stress only discourages them further from seeking help from services or enrolling in sport programs.

According to Statistics Canada, immigrant families are 32 per cent less likely to participate in sports in comparison to children of Canadian-born parents in 2005. Reasons include integrating into a new economy and environment. There are no recent studies of kid sport participation in Canada for low-income and immigrant families.

“Sports is usually not a high priority for families who are also low-income just because of the high cost of living or other things,” says Jamal.

Similarly, Holt says when it comes to new Canadians, the challenge is them being introduced to the available options such as recreational sports clubs and sources of funding from local community centres.

“When it comes to removing financial barriers, a strategy is to support the clubs,” Holt says, adding that he would like to see more opportunities and subsidies made available to participants.

“When you have cities working with their citizens to help provide sporting [programs]…it then helps fund support for grassroots participation.”

Holt mentions as an example that there is an organization in Edmonton that provides free after-school sport programs and transportation from school to the local community centre. “Centres for newcomers and other support help kids make friends, get connected to the community and give them something to do that’s fun.”

This kind of support allows families with a stay-at-home parent, ones with multiple kids and ones who work multiple jobs to still send their kids to programs without worrying about barriers.

llahyarian recalls stretching the truth about having a certain amount of money as a kid to try and fit it. He said that as a kid, you don’t understand that money isn’t everything because you just want to be there with everyone else to play.

“Now we’re adults but you feel almost ashamed,” he says. “You shouldn’t have to lie about things like that, why do I gotta fit the status quo?”

When he moved to Toronto, Allahyarian had teammates and friends growing up who also struggled with financial barriers to sports, and says not all people will have the attitude of channelling rejection elsewhere, and will instead feel depressed about being unable to play.

“It’s okay to not feel okay, but don’t let that feeling last too long…I can say myself not even getting the opportunity to be on these teams had me feeling a [certain] way. But I never looked back and let that feeling last too long.”

There are so many good players he would get to know those days playing at the park when he was in high school. But they wouldn’t play on teams—not because they weren’t good, but because they couldn’t pay to participate growing up.

If it was in Allahyarian’s power to do so, he would make all sports programs free. Now, as a Rams and Ryerson alumni, Allahyarian doesn’t believe in paying to play sports. “I don’t know if that’s maybe the traumatic experiences of my childhood not being able to afford it…but I’m not paying to play. I’ll go to the park or whatever.”

Leave a Reply