Racialized students at Ryerson say they feel unseen and unheard when it comes to reporting harassment and racism

Words by Abeer Khan

Illustrations by Laila Amer

CONTENT WARNING: This article contains mentions of sexual violence, abuse and trauma.

In June, during a surge in the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, Nikita Sankreacha fell into a right-wing rabbit hole. Minutes turned into hours as she scrolled through post after post of racist and anti-immigrant content uploaded by students who attended her own university and beyond. A few days prior, Sankreacha was shocked when she found out about a student at Ryerson named Tyler Russell via social media.

On Twitter, Russell identifies as a nationalist and a paleoconservative. According to an article in Vox, paleoconservatism is a political ideology that stresses Christian ethics, isolationism and traditional conservatism. In tweets and through his live show, The Russell Report, he has expressed nationalist, anti-immigrant and anti-Black rhetoric. Russell responded to request for comment with a video of three men dancing to a song that looped “Shut up, bitch” with text that read “Das rite I’m a nationalist. What you gonna do about it?”

Sankreacha started digging deeper into Russell’s online presence: his Discord chats, the people who engaged with his tweets; she even watched his livestream under fake names.

As an Indian woman who immigrated to Canada about 20 years ago, the fifth-year language and intercultural relations student felt angered and frustrated by these posts—she couldn’t grasp how someone would be comfortable saying what she found to be such hateful statements in a public setting. It infuriated her that Russell was making these claims, and she was even saddened by how there were people who agreed and engaged with his platform positively.

Seeing several students circulating Russell’s posts, urging one another to email the university, Sankreacha decided to start a petition titled, “Expel Tyler Russell Immediately” on Change.org, an online petition platform. The petition garnered widespread attention online as it finally gave Ryerson community members a place to centrally voice their concerns about Russell.

“This is my community. If I want to make a change, it needs to be a local change,” says Sankreacha.

As the petition gained attention, she received a Facebook message, seen by The Eyeopener, from an executive member of Ryerson Conservatives. The message warned her that what she was doing would have “consequences,” and “to never forget that.” While she didn’t think much of it at first, Sankreacha soon began to feel paranoid turning on her camera during her summer classes because she didn’t want Russell or someone associated with Russell to find out where she lived.

Ryerson Conservatives did not respond to request for comment.

Once the petition reached 500 signatures, Sankreacha decided she had enough support from students to send the petition and the threat she received to Ryerson’s administration, in hopes that they would take action—since they continued to post on social media about how they stood behind Black, Indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC) staff and faculty.

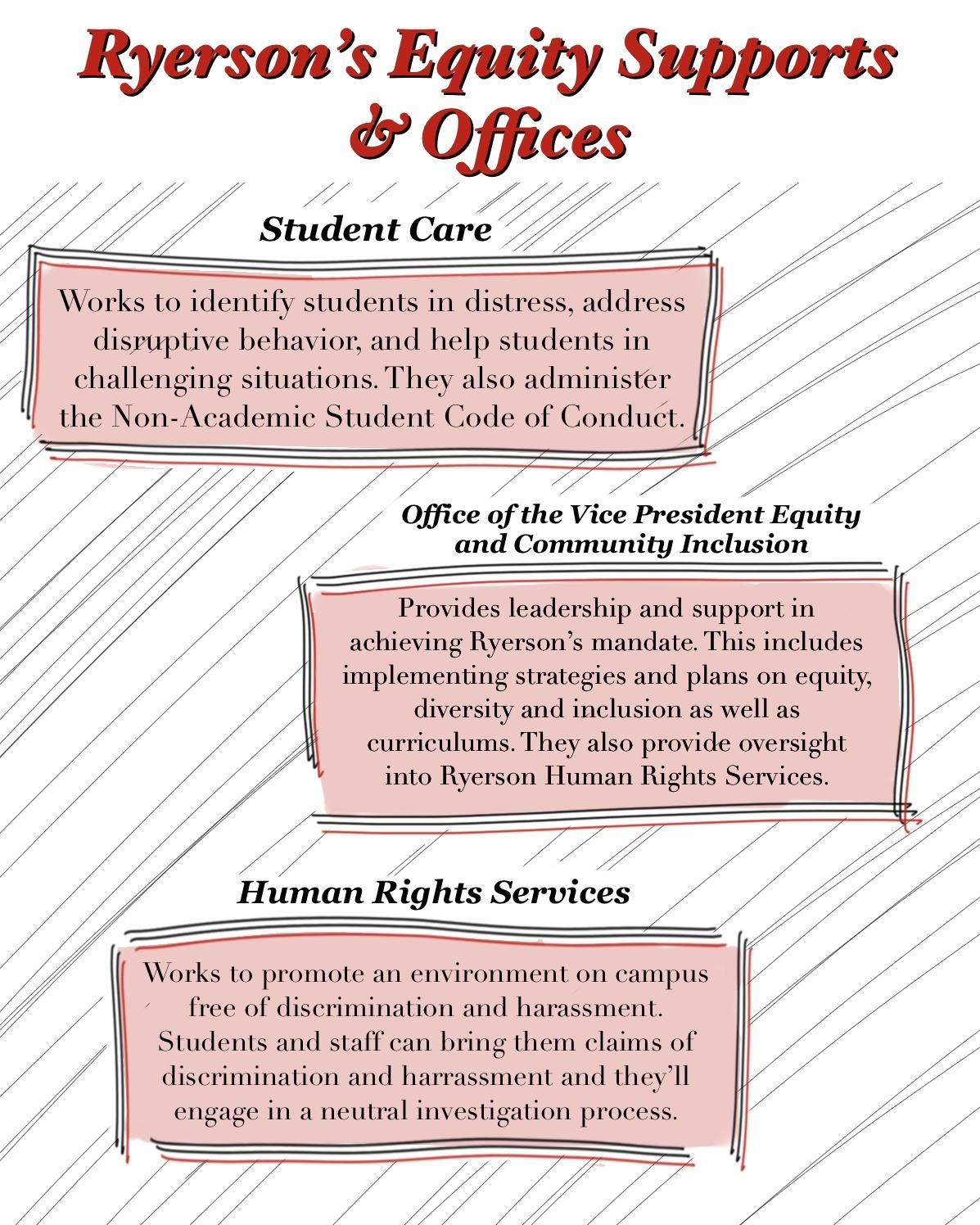

According to a statement from Ryerson, the Student Care office works with Ryerson to identify students in distress, address disruptive behavior and help students in challenging situations. Student Care is specifically responsible for administering Ryerson’s Student Code of Non-Academic Conduct (Policy 61), which Sankreacha felt Russell violated.

According to the university’s website, Policy 61, “reflects the expectation that students will conduct themselves in a manner consistent with generally accepted standards of behaviour…” The policy states that students must comply with university regulations and policies, follow federal, provincial and municipal laws, as well as professional standards and codes of ethics.

Sankreacha spent weeks exchanging emails back and forth with Ryerson’s administration. She emailed leaders like the associate dean of Arts, the interim chair of the politics and public Administration program and countless others. Every reply redirected her to a different person or department to handle her case.

All the replies started to sound the same—“I’m sorry for not replying sooner,” and “I’m so sorry to hear that this is happening,” and none offered tangible steps the university would take to reprimand Russell for his actions. She says each response shut her down with nice words and left her emotionally exhausted.

“There was really nothing from the emails that brought me comfort because there’s nothing I could expect [from them],” she says.

In an official statement to The Eyeopener via email, the university said, “While we cannot comment on specific investigations or complaints, we can confirm that the university thoroughly examines all complaints regarding violations of university policies and the university adjudicates them whenever it is appropriate to do so. The university takes information like this very seriously.”

“I felt like there was a lot of work put on the victim,” Sankreacha says. She felt that she was being asked to make adjustments to her academic experience instead of hearing about what was being done to address Russell and the person who sent her the message. She wondered if Ryerson was contacting them as much as they contacted her.

BIPOC students attaining a post-secondary education often navigate through institutional racism from both the university they pay thousands of dollars to attend, sometimes in addition to microaggressions and harassment from their peers who may face minimal, if any, repercussions.

For racialized Ryerson students like Sankreacha, a lack of meaningful institutional support and well-defined regulations can leave them feeling isolated, hurt and less motivated to continue with their education and careers.

According to Luis Martinez-Fernandez, a professor from the University of Central Florida, up until the 1960s or 70s, institutions of higher education were essentially for white men. While he recognizes that’s been changing over time, he feels that there’s aspects of growth that haven’t developed in a parallel way.

He says there’s sometimes a lot of lip service at institutions like universities, even if they’ve done a lot of good in the area of improving opportunities for marginalized students and their academic success.

He adds that BIPOC don’t have proportionate power in higher education. In his 35 years of teaching at the university level, he says it’s rare to see an actual commitment to do something long-term and transformational in terms of racism and accountability.

When it comes to students who feel a lack of support from equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) offices, Martinez-Fernandez feels that they exist primarily to protect students and people in those offices should always aim to put their students first. He says that protecting the university’s reputation is a responsibility of the public relations office.

According to the Ryerson Human Rights Services annual reports from 2016 to 2018, there were more than 300 complaints made to the Office of Vice President Equity and Community Inclusion (OVPECI). Of the over 300 cases, they say 50 per cent were solved at the inquiry stage. Of the remaining, 25 per cent reached consultation, eight per cent reached an alternative solution and 17 per cent reached the investigation stage.

Sankreacha says that focusing on numerical efficiency when trying to address the concerns of students with serious complaints is a redundant approach, it doesn’t let students who have been helped tell their own stories.

“These numbers focus on the administration’s performance as opposed to how their actual performance impacted students,” says Sankreacha. She says she’d be more interested in how the students actually feel about the OVPECI and the complaint process, rather than just case statistics.

While Ryerson prides itself on maintaining “a visible presence for equity, diversity and inclusion and Indigenous values,” it remains just that—a visible presence. As inclusive as their actions and practices may look on paper, when it comes to actioning these values, BIPOC students at Ryerson can feel a disconnect with the image of support that the university puts forth.

ast year, as Hira Moran* was sitting and eating lunch with their friends, they were approached by their abuser. Moran only remembers dropping their food and running away as their friends frantically went after them confused and unaware of what was happening.

Shaking and crying, Moran went into a dissociative state—they couldn’t make out where they were or what was going on. Eventually, their friends took them to the Consent Comes First office at Ryerson where Moran was able to get some help.

Consent Comes First provides support to Ryerson community members affected by sexual violence. They made sure Moran was okay and helped them come up with a safety plan by opening up their space for Moran when they felt unsafe. They also connected them with on-campus resources like counselling. But since they were abused off-campus and before they enrolled at Ryerson, when it came to taking action against their abuser—a current Ryerson student—there was little that they could do without filing a police report; something that Moran felt unsafe doing.

“The intersections of my identity do not allow for me to be safe everywhere, especially with police,” says Moran. “[With] the history of violence that they’ve perpetuated to every single one of my communities, I just don’t have the option of feeling safe.”

Moran, a fourth-year sociology student, is queer, transgender, disabled, Indigneous-Latinx and a survivor of sexual assault.

The Toronto Police Services don’t have a positive relationship with Black and Indigenous communities. In August, a report from the Ontario Human Rights Commission found that Black people are more likely to be charged or have force used against them during interactions with Toronto police. The study found that although Black people only make up 8.8 per cent of Toronto’s population, they represent almost 32 per cent of people charged. Across Canada, while Indigenous people only make up five per cent of the Canadian population, they account for 30 per cent of the federally incarcerated population, according to a January report from the Canadian government.

This June, the Toronto Police were in the family apartment of Afro-Indigenous woman Regis Korchinski-Paquet, when she fell to her death from her balcony. According to CBC, while Ontario’s Special Investigation Unit (SIU) has cleared the police officers involved of any wrongdoing in her death, her family still feels that the investigation lacked transparency.

According to a report on sexual assault reporting in Canada by the West Coast Legal Education and Action Fund, only five per cent of sexual assault survivors in Canada reported their experiences to the police in 2014. In a General Social Survey on Victimization cited in the report, 26 per cent of survivors who participated believed police would’ve been ineffective, 13 per cent said their past experiences with police had been unsatisfactory and 13 per cent believed the police would have been biased.

When Moran was told they would have to file a police report in order for Ryerson to take action, they felt a sense of disappointment and frustration. While trying to calm their body down after a traumatic experience, they were told that their only option before Ryerson could do anything was to go to the police—something that wasn’t feasible for them. they felt a sense of disappointment and frustration.

Moran says that asking people like themselves to go to the police is an outdated solution and that the university should have more of its own policies in place independent from police. They say that they feel there are many ways to deescalate situations and keep students and survivors safe on campus without involving the police, and that starts with asking those students what they need to feel safe.

Risa L. Lieberwitz, a professor of labour and employment law at Cornell University, says that while institutions have multiple offices set up to help victims of sexual assault, racism and discrimination, they should be composed of the various community members that make up the university—from faculty members to student staff and student groups.

She believes that offices for diversity and inclusion shouldn’t just consist of professionals who are trained for those purposes, but should also operate with guidance and input from the people they serve, along with experts like professors and educators who have different backgrounds and perspectives.

“If those offices start to feel like they’re managing problems, as opposed to really going to the root and the foundations of the problem, then it can start to feel alienating to the people that are supposed to be served by the offices,” Lieberwitz says.

She explains that universities have started to take a corporate-like approach to governance when they should be taking a democratic approach instead. “If structures are set up so that they are more managerial and top down rather than truly inclusive with how offices are created and policies are written, then it’s very difficult for them to function in a way that integrates the voices of the students and the faculty.”

Ryerson has three main entities to deal with racism and discrimination. Student Care works to identify and help students in distress and address disruptive behaviour. They are also responsible for administering Policy 61. The OVPECI offers leadership and oversight into equity and community inclusion initiatives and practices across campus. They oversee the third entity, Ryerson Human Rights Services, who promote a work and study environment at the university that is free from discrimination. Claims of discrimination and harassment are addressed by them through an investigation process.

Moran is also no stranger to racism on campus; it’s something they have been subject to throughout their academic career by the university and their peers.

Sitting at the very front of the Podium arts lab, Moran was working with their friends on a statistics project when a one of their classmates, a white woman, confidently approached them. The woman asked Moran about a text she’d sent them, which they had not yet replied to.

During the exchange, the woman said, “Oh, you’re Latina. You guys all have attitudes,”’ in front of the whole classroom.

No one said anything. The woman was able to misgender and perpetuate a harmful stereotype against Moran without any repercussions. At that moment, Moran didn’t feel like it was their job to educate their classmate on her harmful words and attitude, but was not surprised that the room stayed silent.

Moran says these are not isolated incidents and that they have been a victim of this woman’s racist microaggressions throughout their time at Ryerson.

These incidents on campus coupled with their own personal issues have drastically impacted Moran’s mental health. They say there were times during the years where they wouldn’t get out of bed or go to school. Moran feels that racism on campus can be attributed to the lack of accountability that students—especially white students—face from the institution. They say that compared to the widespread enforceability of the Academic Code of Conduct, they believe Policy 61 is not as advertised or enforced to the same extent.

“I can’t be,” says Moran. “Ryerson enforces that I can’t exist by having these people around me that are constantly saying racist stuff to me. ”

Moran urges the university to not only update Policy 61 to better protect BIPOC students, but to also advertise and enforce it so that students know about it and take it as seriously as they do the Academic Code of Conduct. Over the course of the summer, Sankreacha’s anger and frustration has simmered down to sadness and a reevaluation of her future as she started questioning whether she had the strength, energy, money and connections that she’d need to reach her goals of one day being a professor.

hroughout her undergrad, Sankreacha was constantly thinking about how she could carry concepts she learned into her own future pedagogical approach. She collected readings that she hoped to assign one day, thought about how research could carry her on to her PhD and dreamed about classes she could teach in the future. She was interested in moving forward and doing her masters and PhD in anthropology or linguistics. However, this experience with Ryerson and the lack of care for her case has made her reevaluate her life trajectory. She feels that the systemic problems within academia are “haunting.”

“What I want to do and what I want to be and what I’m good at can only go so far in a system that is set up for me to not do well,” she says.

According to a 2018 report from the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT), racialized women are the most under-represented among full-year, full-time professors and instructors, with 45 per cent working in universities and only 32 per cent in colleges. The wage gap is the deepest for racialized women college instructors, who earn 63 cents on the dollar. Unemployment rates are also the highest for racialized women university faculty at about nine per cent.

On July 17, the OVPECI released the Anti-Black Racism Campus Climate Review Report, which was originally expected to be published by the end of 2019. The Black Liberation Collective (BLC) at Ryerson criticized the reports’ failure to hold Ryerson responsible for their anti-Black racism. The university said that all academic institutions deal with racism—something that the BLC felt lacked accountability.

Even on a faculty level, BIPOC professors feel a lack of meaningful support from the university.

Ryerson is facing two Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario complaints on the basis of racial discrimination: one from Pria Nippak, who faced six years of harassment as a Ted Rogers School of Management professor, and Carol Sutherland, a former OVPECI staff member who was fired while on medical leave. Sutherland’s union has filed three grievances against the university.

In light of her realizations about academia, Sankreacha plans to translate what she loves about academia—experiential learning, theory and research—into other goals that lie beyond the limits of systemic racism and discrimination.

“These things are not just owned by academia…you can learn outside of school all the time.”

As for her goals with the petition, Sankreacha hoped that Ryerson would be a leader and work towards making a difference and creating a safer environment for BIPOC students; an environment free from hate. However, as emails dragged on for months and Sankreacha saw no action being taken, she gave up.

Her final email statement to Ryerson read, “I have noticed this issue change from being about expelling one boy, to urging Ryerson to be better, to sadly accepting that academia, as an institution, is flawed.”

Creating the petition was a step towards creating change for Sankreacha within her community for other BIPOC students and faculty at the university. She had hoped that Ryerson would be leaders in addressing racism from students online and take action to make their community safer, especially given the political climate.

She says that Ryerson and other universities jumping on what has become an EDI bandwagon don’t seem to want to cause any trouble, without actually realizing that the entire point of anti-racism work is to cause ripples in the water.

“When the entire world decided to try and get behind the movement, Ryerson said they were doing that, but in the actual moment, they were not doing it at all.”

*Name has been changed to protect source’s safety and privacy

Update: This article has been updated to reflect that Ryerson Campus Conservatives has rebranded as Ryerson Conservatives.

Kyle Frank

Tyler Russell is a dangerous neo nazi alt right self described “fashy goy”, I am watching his show rn to study how the nazi’s are spreading throughout our campus. By the way everything I have said prior to this sentence has been a meme I dont even go to this school but Tyler is a cool guy so fuck you

CFPatriot

This “article” shamelessly attempts to slander Tyler L. Russell, a Canada First Conservative. Shame on The EyeOpener for allowing this hot garbage.

A Roberts

How is it slander or libel if Tyler’s posts are indeed what the article has described? There is scientific and circumstantial evidence that, most adherents of right wing nationalism tend to commit mass shootings though.

CFPatriot

What are you talking about? The article describes him as a “racist” and “Anti-Black” and a load of other cultural Marxist buzzwords meant to smear anyone who is a Canadian Nationalist.

>There is scientific and circumstantial evidence that, most adherents of right wing nationalism tend to commit mass shootings though

There are millions of nationalists, and only a fringe minority of them commit acts of violence. Also, can you name me a single Paleoconservative who has committed a mass shooter?

Callum Downe

PLEASE tell me this is parody. It cannot be serious. Intersection theory is a cancer on humanity. Sadly, one that is metastasizing.

Bryan Trottier

Doesn’t sound like they are at all unsupported, to me. Seems more a case of making unreasonable demands that their every whim be catered to, at the expense of the rights of others, such as due process and the presumption of innocence.

CF Always

This “article” is nothing more than a shameful hit piece. Tyler is a patriot who simply wants what is best for Canada and it’s citizens. All you accomplish by publishing these slanderous works of fiction is giving Tyler more attention and bringing more people into the movement. Canada First is inevitable!