students with accommodations feel disconnected, unmotivated and isolated in the online learning landscape.

Words by Emma Moore

Illustrations by Jes Mason

CONTENT WARNING: This article contains mentions of ableism and mental illness.

When it was announced that Ryerson’s fall semester would be online, second-year professional communications student Liam Shapiro thought he’d be fine. He had a 3.66 GPA and was right on track to meet the 3.0 GPA requirement to be eligible for an internship in the spring semester of his third year.

Shapiro has accommodations for his Aspergers, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and a chronic illness. His accommodations allow him to sign up to receive notes from a volunteer peer note-taker through the RU Noted program, which is the notetaker portal offered through Academic Accommodation Support (AAS). Feeling optimistic about the term, he logged in in September and signed up to choose a volunteer notetaker.

According to the RU Noted website, the service doesn’t generally provide notes for online courses. They also state that notes shouldn’t be requested unless a course is being livestreamed, meaning asynchronous courses aren’t eligible for notetakers.

Most of Shapiro’s classes are delivered via Zoom. He’s attended all of his lectures, but in terms of course content, he says he has no clue what’s going on. Due to health complications, he isn’t able to take medication for his ADHD, which prevents him from being able to focus during his online classes.

“It’s not that I’m not absorbing the content that’s given to me when I’m in class. It’s that I’m unable to condense it down into proper notes,” he says.

“It pisses me off to think that I’m going to be locked out of this [internship opportunity] for something that I can’t control. It is not my choice to have everything online and especially not my choice to be unable to take notes and to function properly in class,” he says.

Pre-pandemic, if he was having difficulties with his accommodations, he’d just go to AAS’ drop-in hours. Now he says that going through the effort of setting up a meeting doesn’t feel worth it.

Notetakers are only available if people in the class volunteer to upload their notes. Even if he set up a meeting with his advisor, Shapiro doesn’t think they’d be able to help him.

“I’d basically be speaking to them to vent,” he says.

Last year, a week into his first year at Ryerson, Shapiro had walked out of the elevators into the fourth floor of the Sheldon and Tracy Levy Student Learning Centre (SLC). Strolling up to the front desk, he requested to have a meeting with the student accommodation facilitator that was in that day.

In highschool, he had received accommodations, so he knew what to expect from the meeting. The advisor booted up her computer and began discussing his options for the different supports available to him—extra time on assignments and tests, access to a notetaker, and breaks during exams.

While Shapiro wasn’t nervous about setting up accommodations, he still left the office that day feeling relieved. He walked in seeking accommodations and walked out within the day with them sorted out.

For Shapiro, the physical office itself played a role in making it easier for him to seek accommodations. It was comforting to get things done in-person and there was a sense of security that came with being physically present in the appointment.

In a statement from Ryerson, they said that accessibility and inclusion has always been a priority for the university, even before the pandemic. They “aim to ensure that all systems and technology procured are accessible to everyone.”

To prepare faculty for accessible online learning, Ryerson’s Centre for Excellence in Learning and Teaching (CELT) made an accessible course outline template for faculty use, as well as a survey that can be used to assess students’ access to technology. These topics were also covered in workshops on Universal Design for Learning and Flexible Learning, for which the recordings have been made available for anyone who was unable to attend the live session.

Most students have concerns about the online semester. Whether you’re worried about your microphone accidentally turning on, your internet being too slow, or your focus drifting during Zoom lectures; it’s entirely common to feel afraid of what this semester has to bring.

But for students with disabilities and accommodations, the shift to online learning will be more difficult, according to Jessica Vorstermans, an assistant professor at the York University critical disability studies program.

“It’s going to be compounded for students with disabilities who are still going to face ableism in the online space,” she says.

Vorstermans says that while COVID-19 has broken down barriers for accessibility in the sense that structural barriers like transportation are removed, the idea that the virtual space will be inherently better for people with disabilities is a simplistic way of thinking.

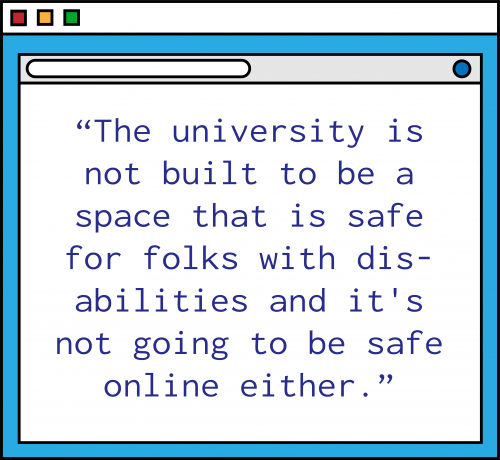

“Society and the university are disabling spaces, they’re not spaces built for disabled bodies…COVID has really deepened that,” she says. “It’s a lot larger than just access to campus.”

“University is not built to be a space that is safe for folks with disabilities and it’s not going to be safe online either.”

She says that while dealing with all the issues their able-bodied and neurotypical peers are facing, students with disabilities have other factors to consider as well. Whether it be the worry of not having notetakers, peer isolation, or professors not being accommodating, it’s clear that virtual learning puts a strain on many students. But those with disabilities face an intersection of challenges.

Prior to the pandemic, students with disabilities already faced numerous barriers to accessing post secondary education. The 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability revealed that 14 per cent of persons with disabilities had graduated with a certificate, diploma or bachelor’s degree, versus 27 per cent of persons without disabilities.

“Having ableism be the norm is still going to happen in the online space,” Vorstermans says.

Anne Jackson, a PhD candidate in critical disability studies at York University says that most students and faculty are just struggling to maintain some normalcy at the moment. With people feeling overworked from floods of emails, she says it may lead to students with disabilities slipping through the cracks. “People with disabilities [and] the elderly are always the ones that suffer repercussions of rapid change,” she says.

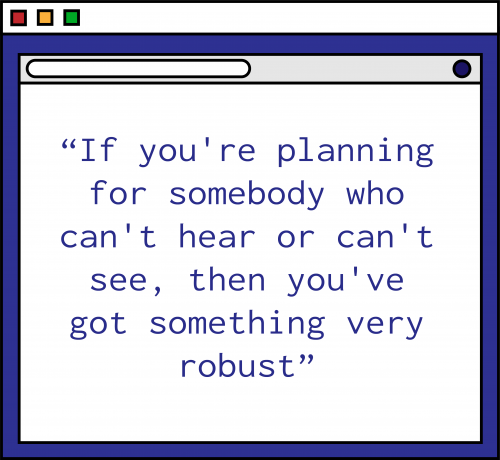

She finds that most systems are built with able-bodied people as the target user in mind. She thinks it would be best for everyone if we did things the other way around, and create systems with people with disabilities as the target audience first, rather than struggling for short-term solutions later.

“If you’re [planning] for somebody who can’t hear or can’t see, then you’ve got something very robust,” she says.

t the beginning of each semester, Idrees Doyle* consults his syllabi in order to book his time in the testing centre—ten days in advance of the test.

In his second year of biomedical sciences, he missed that deadline for his biology midterm. The professor and his peers mentioned it frequently in class, so he knew it was coming up—he just didn’t have the motivation to do anything about it. At the time he was “in a dark place” with his mental health, he says. Doyle has depression, and he felt like two sides of him were at play; he felt indifferent, but at the same time felt unsettled by his own indifference. He didn’t fail the test, but he felt hopeless while he was writing it.

Now in his fourth year, Doyle worries that students with mental illness are going to be left adrift. He describes setting up accommodations as a complicated process.

In his science courses, he found that while his professors were mostly quite understanding about his accommodations, it still took significant time and effort on his part.

Students will now have to send a plethora of emails to negotiate what would have already taken an hour during office hours, he says.

He says that many people with mental illness struggle with a lack of motivation and may find the process of securing accommodations to be discouraging. Doyle thinks that if someone is suffering from similar issues, they might lose the motivation to deal with these hurdles if they come up in the online term.

“It’s so easy to just fall behind because you get so caught up in…what you’re suffering from.”

Tracy Orr, an educational researcher and instructor at Portage College conducted research into how women in online learning experienced and recovered from depression. She says that it’s important that online courses are designed to emphasize clarity and readability, with minimal redirection or navigation to counter the fatigue and lack of energy experienced by students with depression.

Fatigue in the online learning landscape can affect the effectiveness of many students’ accommodations.

Fourth-year photography studies student Kashif Bin Arif says there are some perks to being able to learn from home, but a lot of things also make it tiring for him as a Deaf student. Whether he’s paying attention to his American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters during lecture, attending meetings, or doing readings, he is often stuck inside, having to pay his undivided attention to the screen. Some days he has to spend 10-12 hours glued in front of his laptop. He says while students who can hear can maybe turn off their camera or do something else while watching a lecture, he doesn’t have that luxury.

While he has great support from his accommodations as well as his professors, there are still ways that his accommodations are hindered by the virtual landscape.

“It doesn’t matter how great my accommodations are,” he says. “We’re at the mercy of WiFi…I might not be able to see my interpreters that well if screens are freezing up.”

Bin Arif also finds that being fully online as a Deaf student has affected his motivation and support systems. He says students who can hear have an easier time forming connections in class and can easily chat with each other, but he always feels like he has to do extra work.

“It really amplifies my solitude or my loneliness,” he says. “Deaf individuals communicate in a visual way…I feel like it’s double the impact for me, because not only am I learning as you are, but I’m also learning how to manage all of this information.”

In order to access information during lectures as well as after class, Bin Arif needs to be given co-host access by his instructors on Zoom so that he can pin both of his ASL interpreters onscreen. While most of his professors are supportive, he says many of them don’t know how to pin properly or have the correct version of Zoom downloaded or ensure his ASL interpreters are present for him. Instead, a lot of that falls on his shoulders.

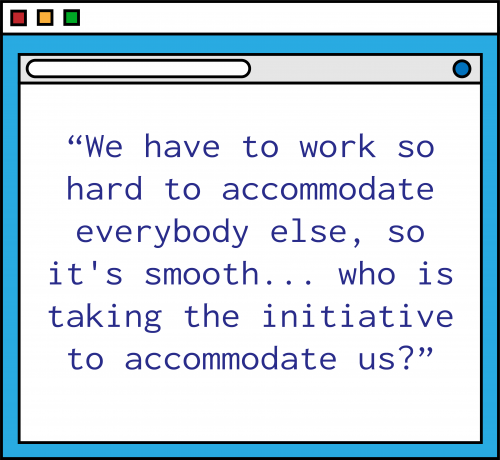

“It’s really important that I advocate for my accessibility,” Bin Arif says. “We have so much to do, like all students do…but then to have the extra added layer of advocacy, of explaining—there’s a lot of tension and stress and anxiety around that.”

Jackson believes that some best practices for accessibility in a virtual setting include offering content in different forms. “Accessibility is giving people a variety of formats [to] be able to choose from so that the technologies that they have help them to communicate and learn.” She recommends asking people what their accommodations are, and asking them the best ways they can provide support.

Bin Arif agrees that in order to support students with extra accommodations, people need to educate themselves and take on the responsibility of advocacy.

“We have to work so hard to accommodate everybody else, so it’s smooth,” he says. “But who is taking the initiative to accommodate us?”

“I wish it would be the other way around, not me accommodating you to make your teaching or your platform smoother. It’d be nice to have that accommodation on me.”

rekking across Ryerson’s campus from the library to the Ted Rogers School of Management (TRSM), Talia Emanuel and a small group of classmates were deep in discussion about what might be on their impending business test. She was in her first year in the hospitality and tourism management program and they had just finished studying.

As they headed towards Yonge-Dundas Square, they passed the Victoria Building. Emanuel, distracted by the conversation, missed it as they walked by.

The Victoria Building houses the testing centre at Ryerson, where students with accommodations can write their tests and exams. Emanuel has Type 1 diabetes, and some of her accommodations include being able to write exams in a private testing room in case she needs to check her blood sugar or eat during the test.

Once they reached Dundas and Victoria, Emanuel told her classmates she would see them later because she had to write her test in the testing centre. One of her classmates turned to her, casual confusion scribbled across his face.

“Why are you going to the testing centre?” he said. “I thought you were smart.”

It took a second for what he meant to register. When she got to the testing centre, the initial surprise wore off and annoyance settled in. Many of the students with accomodations who were signing into the testing centre were people she knew were receiving honours and recognition from the university for their achievements.

The public perception of students who need accommodations as not being intelligent doesn’t make sense, Emanuel says. She is currently pursuing a Master of Science in Management at Ryerson. When people receive the accommodations that they need to manage their disabilities, they are just as capable of achieving academic accomplishments.

“The point of accommodations is that what’s being evaluated is my ability to do the work at hand. Not my ability to manage my disability or how much my disability really impacts me,” she says.

Another time, during a week of welcome in second year, Emanuel was placed in a small group of strangers for a scavenger hunt activity. At one point, when she pulled out her insulin pump, she had to explain to her group that she was a Type 1 diabetic.

One of the women was shocked, rushing to tell Emanuel that she was so sorry for her, that she couldn’t imagine having to give herself a needle and that she wouldn’t be able to live with herself if she had to live with Emanuel’s disability.

Emanuel explained to the woman that there isn’t a choice in the matter. “I think you probably could. I think if your choices are either actually not living or taking injections…you’re probably going to choose the injections.”

Attitudinal barriers regarding ableism are a major challenge for students with disabilities, according to a 2018 National Educational Association of Disabled Students report. These include implicit biases based on stereotypical ideas about disability and stigma, such as what Emanuel experienced.

The report says that “it is a truly taxing endeavour that causes a student to devote their time, energy and resources to the constant articulation of their needs that could otherwise be devoted to study, social integration and academic learning.”

These ableist encounters with peers were always uncomfortable and frustrating and she would vent to a trusted group of friends afterwards. However, Emanuel reflects on it in a positive way; now that she’s had these experiences with people, they might be more understanding and view people with disabilities differently in the future.

“It makes it easier for the next [disabled] person who comes after you,” she says.

According to a 2017 research article on the attitudes of university students toward persons with disabilities, these negative perceptions of people with disabilities develop because of insufficient and incorrect information about disability. It says that when there’s increased personal contact with members of marginalized groups, such as in a university setting, that these perceptions are likely to improve.

But now Emanuel worries that this personal contact won’t occur online. As well, she’s concerned that when group work is assigned, people with disabilities will be shafted.

Even under normal circumstances, choosing who to work with for a school project is stressful. That stress is only compounded for students like Emanuel who need to also decide if they feel comfortable disclosing their disability to their peers when explaining that they may need extra time or other considerations.

According to a 2019 Journal of Business and Psychology study, when applying for jobs, people may conceal their disability from a potential employer because it may decrease the likelihood of them getting the job due to negative stereotypes about disability.

In a university setting, it can be assumed that this would translate into the likelihood of getting chosen for a group project. The study also mentioned that people react to late disclosures negatively.

If a student doesn’t feel comfortable advocating for themselves, or giving specific details to their group members, this can create a really uncomfortable position for students with disabilities, says Emanuel.

Emanuel thinks that online classes may help in some ways—if a student with a disability is absent from class for medical reasons, it won’t be as obvious with virtual learning and they‘ll have more freedom in choosing whether or not to disclose it.

According to the 2019 Journal of Business and Psychology study, a person’s decision to disclose their disability is deeply personal, and is difficult to do when disability is stigmatized.

However, she worries that regardless, students will be losing the value that comes from face-to-face interaction and socialization with others. “You don’t necessarily have people who are forced to question their assumptions or stereotypes.”

ith working from home, there is “this sort of discourse that people are inundated with emails, people are inundated with having to be online so much,” Vorstermans says. But when students like Shapiro don’t receive confirmations of accomodations, it adds another layer of strain.

Three weeks into classes, Shapiro has still not been able to select a notetaker in any of his classes. Without a notetaker, he believes his grades will drop and that the opportunity for an internship will be out of his reach.

“This [is an] added anxiety and stress on students with disabilities. There’s already the anxiety of studying online,” Vorstermans says. But on top of that, students with accomodations still have to worry about ableist systems.

Whenever he finds himself struggling in his classes, he opens a new browser window on his computer and logs in to RU Noted portal, hoping that a notetaker becomes available, that someone has finally uploaded the notes and that maybe his grades won’t drop this semester. Every time, without fail, the words “notetaker not assigned” glare back at him from the computer screen.

Without the safety net of a notetaker, Shapiro feels lost about the rest of term. With his accomodations falling through, he’s not sure what the term is going to look like. If this semester was a race, Shapiro has been left in the dust at the starting line as his classmates run laps around him, he says.

“There’s not much I can do about it…right now the feeling is that I’m lost and it’s kind of hopeless.”

*Name has been changed to protect the source’s privacy

**With files from Dhriti Gupta

Leave a Reply