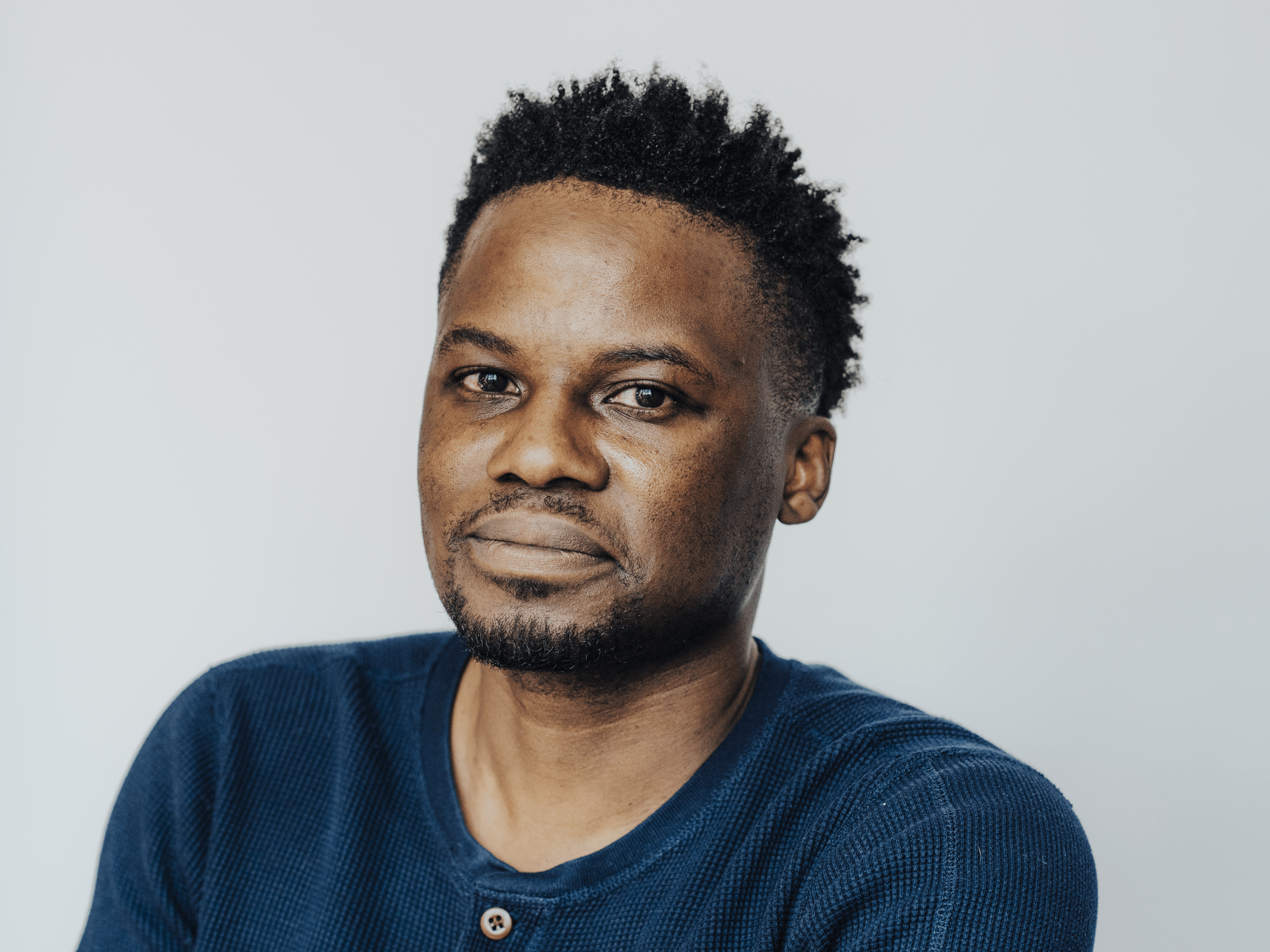

Words by Libaan Osman | Illustrations by Jimmy Kwan

Ryerson law student Ish Aderonmu spent more than 500 hours observing cases at the Superior Court of Justice from 2018 until its shutdown earlier this year due to COVID-19.

He sat through almost every case imaginable and soon enough, he became a regular at the courthouse. It was all in an effort to understand the Canadian justice system and see if a career in law was truly what he wanted to pursue.

But before he was interested in understanding the criminal justice system, the now 36-year-old was part of it—he was arrested about a decade ago in Philadelphia, Pa., for trafficking marijuana.

“I got into the cannabis game a little too early. I’m getting weed shipped in from California to [Philadelphia] and I see this huge opportunity to get out the hood, get out of my parents’ house, all of that stuff,” said Aderonmu. “It’s going really well at the start, but then a package I order comes in hot.”

A shipping delivery gone wrong ended with a dozen police officers pointing guns at him and telling him to get on the ground. His bail was originally set for $200,000—Aderonmu would hire a criminal lawyer that his friend knew to help fight the charges.

Aderonmu wanted to avoid a felony on his record, but during the trial, his lawyer told him a deal was on the table. If he pleaded guilty to possession with intent to deliver a controlled substance, he’d be facing only two years of probation and six months of house arrest. But if they lost the trial, his lawyer said he could be facing up to five years in prison.

With not much time to think the offer through, he agreed to the plea deal.

But what Aderonmu wasn’t told was his guilty plea could affect his immigration status in America. Aderonmu was born in Nigeria but he and his family moved to Winnipeg when he was three years old, and later Toronto.

He and his family became Canadian citizens in 1993 but relocated once again when he was 13 after his father landed a job in Pennsylvania at a prison as an Imam.

Aderonmu would become a legal and permanent resident of the United States, but according to the judge, agreeing to the plea deal had the potential of getting him deported. He was advised not to worry about it; his lawyer said they talked with the district attorney and they wouldn’t pursue that route.

But about a year after his conviction, two Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers arrested Aderonmu while he was out walking his dog. By then, he was already done house arrest, was on probation and would frequently check in with his probation officers. It was nearly two years since his initial arrest, but that didn’t stop ICE.

He was taken to the Department of Homeland Security Office in downtown Philadelphia where he was informed his guilty plea would mean his arrest. He was sent to York County Prison—three hours away from the city.

Aderonmu spent the next month trying to figure out his next move, polling other inmates to figure out what their situation was, how they got there and what his best course of action was. He heard stories of people from Jamaica, Liberia and South Sudan who’d been there for about two to three years. He worried he’d be stuck for just as long.

“My first court day was guaranteed within seven days by law, second court day guaranteed within three weeks by law, third court day zero guarantee. So I knew by talking to other people that their third court day sometimes didn’t show up for another six to eight months,” said Aderonmu.

This led to him asking for a voluntary departure to Canada to try and figure out his situation while being able to live freely. After 45 days, Aderonmu was shipped across the border and found himself moving in with family in Brampton for about six months, before eventually moving back to Toronto.

According to voluntary departure rules in the United States, Aderonmu wouldn’t be allowed to travel back to Philadelphia for at least a decade. That forced him to leave behind family and friends to create a new life in Canada.

“Why’d you move here? Oh, I just got deported from the United States”

For about six years, he bounced from job to job trying to make ends meet, while also trying to find roommates.

Dealing with the stigma and assumptions around his criminal record proved difficult to navigate and made it harder to find a place to live. “When I first got here, I wasn’t telling [anybody],” said Aderonmu. “It’s like ‘Hey, I would like to live with you. Oh, why’d you move here? Oh, I just got deported from the United States.’”

On a few occasions, Aderonmu would find a place and express interest in moving in, only for his potential roommates to say they’d found another person to live with. Upon emailing them under a fake alias, it would turn out that the place was actually still available.

Aderonmu felt vulnerable about opening up about his felony in the past but hiding it made it much tougher to come to grips with his situation. In 2018, he started to embrace that part of his past, realizing that it shouldn’t stop him from moving forward.

One evening he found himself watching 60 minutes—a show he recalls his family watching every Sunday when he was younger. The episode featured Shon Hopwood, a convicted bank robber who became a law professor at Georgetown University.

It opened up Aderonmu’s eyes. “That was the moment where I said I’m going to start to do some research. The fact that Shon Hopwood did it…was enough for me. It’s been done, so I can do it too,” said Aderonmu.

Having been through the criminal justice system, he thought he had a good understanding of the law and felt his own experience could become a case study. Eventually, he found himself calling the Superior Court of Justice on University Avenue his second home, in hopes of pursuing law.

Aderonmu would get in contact with well-known lawyers while specifically looking to those that can relate to his own hardship. This is how he met Jordana Goldlist.

Goldlist experienced homelessness as a teenager and had her own run-ins with the law. Now, she’s considered one of the top criminal defence lawyers in Toronto.

She recalls the first time she met Aderonmu at the courthouse, where Goldlist was arguing a charter application for a client and Aderonmu was just looking to see how it would play out in court.

“Initially, he really just wanted to see if this is what he wanted to do, which I think is amazing,” said Goldlist.

In the past, Goldlist said she’s received emails from people expressing an eagerness to shadow her in court but wouldn’t always follow through. This wasn’t the case for Aderonmu: he sat through one of her team’s proceedings for three days and continued to follow up.

Throughout this process, he was examining his options for education. First, he looked into the University of Toronto’s law school but was turned off by its competitiveness. Then, he set his sights on Osgoode Hall Law School and got in contact with the former dean of the school, who encouraged him to apply and share his story.

Between this and the motivation from Hopwood’s success story, Aderonmu felt like he was on the right path.

“These law schools have been around for 100 years. They weren’t built for people like me”

In November 2018, Aderonmu applied to Osgoode as a mature student. He was rejected, but this didn’t discourage him. His goal remained law school: anything else was a distraction.

“Any events where lawyers were going to be at, I was there. So I got to meet and learn; I had a better perspective,” said Aderonmu.

While networking with individuals in the legal field, he ended up in a Brampton courthouse shadowing a criminal lawyer that told him about Ryerson’s law school which was set to open up in fall 2020.

He started to do his research, began attending events at the university and mingling with people in charge of building the new law school.

With no prior reputation, he saw Ryerson as a place where he could help write a new story. It’s the first new law school in Toronto since 1889. And as a Black man, enrolling in the school made so much sense to him.

“These law schools have been around for 100 years. They weren’t built for people like me…It made sense to go to a place that was starting out new without all the history of exclusion,” said Aderonmu.

He’s now one of 170 students in Ryerson’s inaugural law school class, which is an accomplishment he’s still trying to process.

Back in February, he created a GoFundMe page to raise money to afford more than $70,000 in Ryerson tuition fees and living expenses that he would endure for a year. So far, he’s achieved half of his goal, receiving over $39,000.

“If you know that you have your vision and dream, literally don’t let anyone else inside it”

Goldlist, who wrote a recommendation letter on behalf of Aderonmu, said she’s proud of him but not surprised in the slightest.

“Ish has certainly confirmed that my story is helpful and is helping other people accept that this is something they can do, they can go to law school despite having been to jail or despite having their own personal circumstances of adversity,” said Goldlist.

Aderonmu’s passion for law comes from injustice within the criminal justice system. He plans to centre his education around human rights. He also hopes he can get the chance to eventually be on Ryerson’s law school admission committee to help bring a different perspective to the application process.

This past June, Aderonmu applied for a line of credit for law school but was denied. The credit could’ve helped cover the cost of his fees, but now he is forced to look at other areas to make cash as a student and has considered working another job while studying.

Aderonmu could’ve entered law school without sharing his past and current struggles but wants to use his situation as a case study to show other people who face similar levels of hardship that they are just as capable.

Just this month, he moved into the first apartment he could call his own since he left Philadelphia. “It’s quite emotional, it’s an empty apartment but I’m happy with it. I don’t have a lot of money, but I get a bed and a desk and it’s mine. It’s my place to call home,” said Aderonmu.

“I can say never give up on yourself. If you know that you have your vision and dream, literally don’t let anyone else inside of it. Who cares what anyone else says? Because if I would’ve listened to people, I wouldn’t be here.”

Debbie

WOW! Having worked at the esteemed international law firm Perkins Coie, I AM IMPRESSED!!! He will make an excellent attorney!

Polly

WOW! Having worked at the esteemed global law firm Dentons, why am I not surprised a school facilitating social (in)justice and the victim industry gets sued by the school’s poster child?