By Reedah Hayder

Last year, the city of Toronto saw 37 cyclist injuries of serious or fatal collision, according to Toronto Police Services. Anne Harris, a professor at Ryerson’s School of Occupational and Public Health, explained how her new study, Lane Change: Safer Cycling Infrastructure in Toronto, showed that with better cyclist infrastructure, there would be fewer injuries.

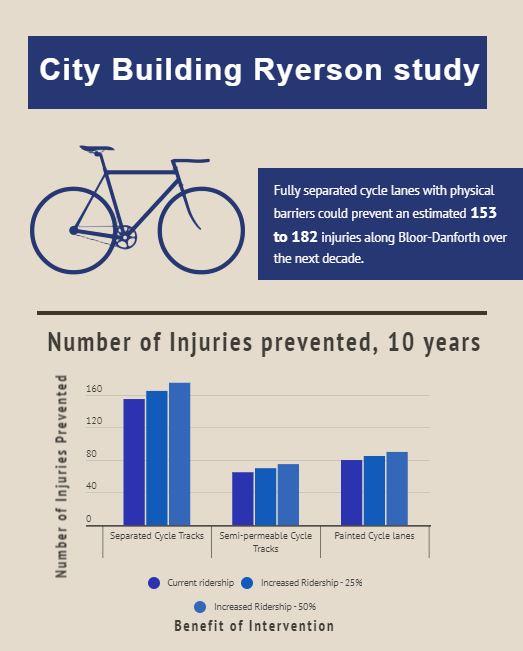

As cycling rates went up in Toronto this past summer, City Building Ryerson, a new institute for research, learning and engagement, looked into how better cyclist infrastructure can prevent cyclist injuries.

The institute investigated how new separated cyclist infrastructure such as cycle tracks and shared roadway routes on Bloor Street West affected the safety of cyclists. It looked at Bloor through Yorkville, and Bloor and Dufferin Streets.

The study looked at what increased cycling means for public health and calculated the number of preventable bicycling injuries, showing that fully separated cyclist lanes could prevent between 153 to 182 injuries along Bloor-Danforth over the next decade.

Researchers Michael Branion-Calles, Calum Thompson and Naing Myint surveyed 690 cyclists in Toronto and Vancouver who sustained injuries while cycling. The researchers then focused on trouble areas where it was common for cyclists to have been injured.

The results found that the farther apart cycling tracks are, the more injuries can be prevented.

During the webinar, Harris explained that cyclist tracks need to be completely separated in order for there to be higher rates of injury prevention. “We also need the routes to be unobstructed because if [they’re] not, this is a risk to cyclists,” she said.

Students at Ryerson who are cyclists also want better cyclist infrastructure in the city and on campus.

Ryerson found that from 2017 to 2018, about 16 per cent of students, faculty and staff biked or walked to the university.

StudentMoveTO, a 2019 study that conducted the largest-ever survey of student transportation, found that most student cyclists in Toronto have an average commute of about 15 minutes.

A 2018 Ryerson study led by professor Raktim Mitra found that 31 per cent students and 23 per cent of faculty and staff members are all-season cyclists, meaning they do not change their commute habits in the winter months. Most said they would cycle more during the winter if there were cycle tracks closer to Ryerson.

This summer, 40 kilometres of on-street bike infrastructure were installed through ActiveTO, an initiative started by Toronto Public Health and transportation services to provide more space for people to be active while physical distancing. The initiative also introduced 15 km of continuous, dedicated space for bikes along Bloor-Danforth.

Devon Santillo, who is a member of Ryerson’s cycling club, said that cycling is his main method of transportation to get to school and around the city.

“I have been sort of an on-call mechanic for everyone at the [cycling] club. I have a garage that I rent near campus and I run a bike shop out of that.”

Santillo said he first took up cycling as a way to be more timely and financially efficient because he feels it can get you around faster and easier.

“I was able to sleep in a lot more before my 8 a.m. lectures and I didn’t have to wait for transit,” said Santillo. “I was my own master of destiny in terms of getting to school on time.”

Santillo said since the pandemic started, he feels more and more people are turning to cycling to not risk crowded capacities on transit.

Harris noted that much of this infrastructure is still considered temporary, which could lead to more injuries given new construction could attract cyclists and leave them without protection once removed

Santillo volunteers at Bike Sauce, a donation-based DIY co-op at Broadview and Gerrard streets. “We’ve only been open about 30 or 40 per cent of our regular hours and we’ve almost made the same profits we did in 2019 just being open a couple days a week.”

Though he said he’s never had a problem cycling in the city—as an enthusiastic mountain biker, he thinks the city’s new isolated cycle lanes encourage more people to cycle.

“People who have been usually pretty anxious in the past to bike alongside cars, feel a lot safer now that there are whole isolated bike lanes with concrete barriers up.”

Santillo said Toronto and the Ryerson campus need more bike lock-ups because of increasing bike thefts in the city, as was previously reported by CBC.

He said that the newly finished Gould Street construction does help clear a path for cyclists, but he thinks once school starts up again with in-person lectures, having pedestrians and cyclists on the same path could cause some trouble.

Design Concept 4c, for the yongeTOmorrow improvement plan—a city initiative to improve pedestrian activity—was chosen to best accommodate cyclists. It provides cycle tracks on part of Yonge Street and three one-way driving access blocks, which provide lower traffic volumes for people cycling.

However, Harris noted that much of this infrastructure is still considered temporary, which could lead to more injuries given new construction could attract cyclists and leave them without protection once removed.

The study’s researchers stated the importance of temporary cyclist infrastructure being moved to be made permanent.

Harris said that since the Gould construction has finished she hasn’t seen it in person but is excited to see it soon.

“It’s important to consider your user base when it comes to cyclist infrastructure.”

During the Campus Core Revitalization project in 2019, cyclists were told they would experience some restrictions and changes to parking locations. Cyclists were also recommended to stick to cycling on city streets outside the project zone.

The Bike Share Toronto station on Victoria Street has been relocated by the intersection of Yonge and Gould Streets. An additional station will be placed at Victoria Street and Dundas Street East when the Campus Core Revitalization project is complete.

Harris said there should also be an emphasis on “fully connected cycling networks equitably distributed throughout the city” as gaps in the cyclist infrastructure can be misguiding and thereby lead to more injuries.

The study also found that there was “safety in numbers.” With higher cycling volumes, there will likely be fewer cyclist injuries.

Harris noted that her study had a limitation in looking at how equity affects who gets injured.

“Concepts of bicycling safety can be framed by personal experiences, including harassment and violence, other than traffic violence, particularly as experienced by marginalized and racialized people,” the study reads.

“We need more information. Ideally, we would do this as a national study to compare provinces and cities,” said Harris.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Devon Santillo works at Cycle Solutions, a bike store on Parliament Street. The Eyeopener regrets this error.

Leave a Reply