By Abeer Khan

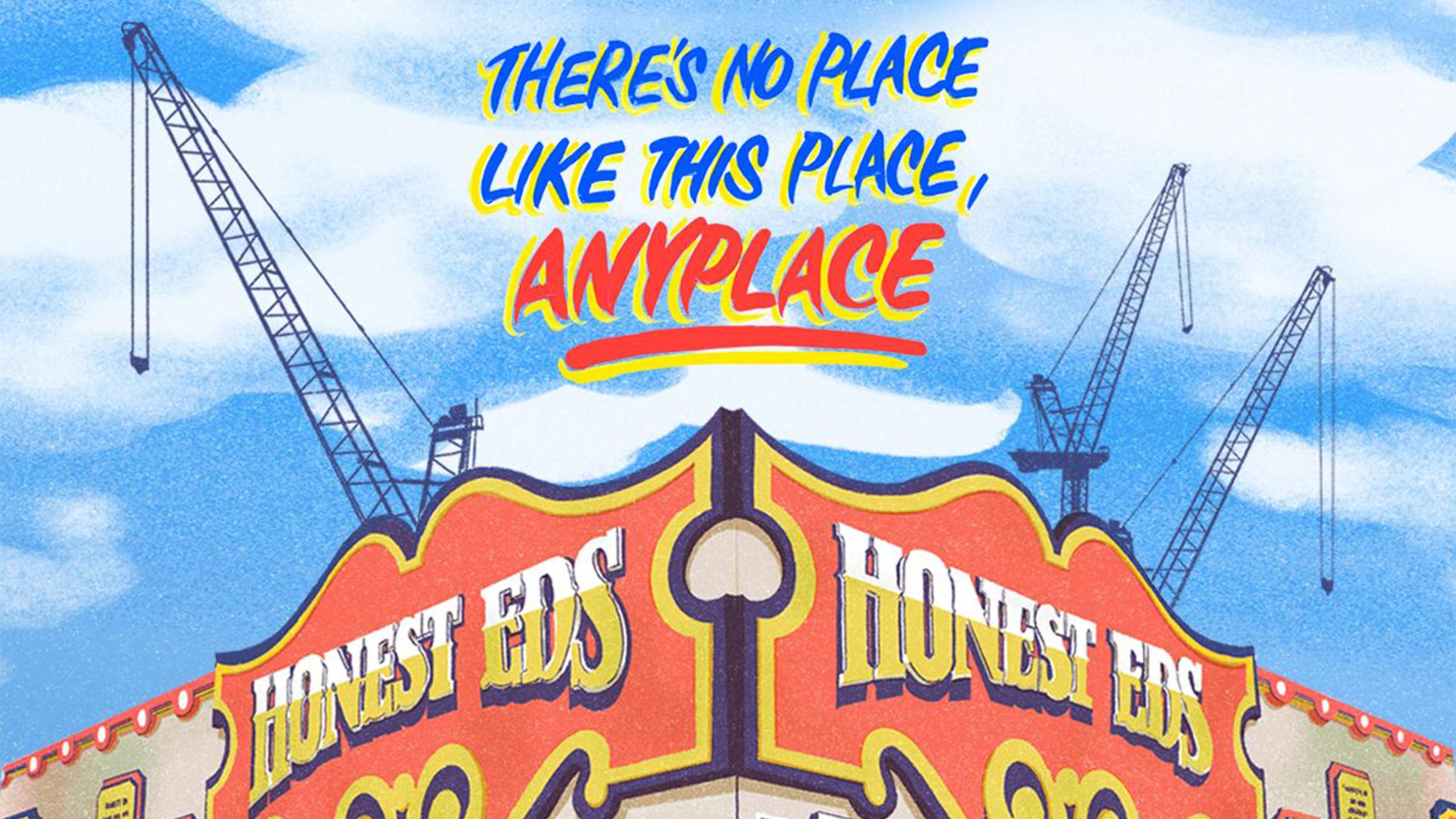

On Dec. 31, 2016, the flashing red and yellow sign of Honest Ed’s glowed for the last time. As the clock struck twelve, the new year began, and after 68 years the department store closed its doors for the last time.

For many in Mirvish Village, Honest Ed’s wasn’t just a department store. In Lulu Wei’s eyes, it was their home.

Wei, who holds a master of fine arts in documentary media from Ryerson, started filming the closure of Honest Ed’s and the sale of the Mirvish Village block as their own passion project. For Wei, this project seemed more like a time capsule: a way to remember their community as it changed before them. They never imagined that it would become their debut film project.

Opened by Ed Mirvish, Honest Ed’s was an iconic discount store at the intersection of Bloor and Bathurst streets that sold low-cost clothing, home goods, groceries and ornaments. According to Wei, it was known for being a hub for newcomers to Canada who needed an affordable place to shop.

In 2013, the Mirvish family announced that the land Honest Ed’s occupied—a 1.8 hectare plot of land that bordered the corner of Bloor and Bathurst and extended west to Markham Street—was up for sale. Later that year, David Mirvish, Ed Mirvish’s son, sold the site to Westbank Properties of Vancouver, who proposed plans to redevelop the area with a community hub and highrise buildings.

“Honest Ed’s felt like another era that somehow lasted”

The title of Wei’s film, There’s No Place Like This Place, Anyplace, was taken from the large slogan that greeted shoppers at the store. The film follows the closure of Honest Ed’s and how Mirvish Village subsequently changes.

“Honest Ed’s felt like another era that somehow lasted,” said Wei. “It sort of represents this part of Toronto that feels like it can’t exist anymore.”

Wei spent four years filming by themself. They started workshopping the film and applying for funding, while making a development teaser. Through this, they received grants, and eventually the film was commissioned by CBC as a one-hour documentary for TV.

Wei said they didn’t originally expect the project to become a feature film until they and their partner Kathleen were impacted by the development. Many tenants, artists and business owners had to move out following the sale of the block. Though Wei’s building was purchased by the City of Toronto rather than Westbank, they had to move too.

Artist and gallery owner Gabor Mezei, an immigrant from Hungary, was one business owner and artist who had to relocate due to the sale. He owned and operated his art gallery, Gallery Gabor Limited, alongside his wife, Margit, for 40 years on Markham Street. In the film, Mezei is seen packing up his art gallery before midnight after 40 years of calling it his own.

Mezei said he misses the atmosphere in Mirvish Village and thrives off his memories of the neighborhood. “Just being there and meeting the other artists and people on the street was a wonderful experience for me,” said Mezei. He still keeps in touch with people from the street today.

He recalled when Wei came in and chatted with him when news of the block’s sale broke and asked him if they could shoot some videos. Wei continued to visit Mezei throughout the years and decided to give him a large part in their documentary.

Wei said the impact on Mirvish Village is significant since it used to hold affordable housing and rental space that’s becoming increasingly rare in Toronto. They say newer developments in the city are all about efficiency and being shiny and new, and are not affordable, which risks pushing folks out.

“It…represents this part of Toronto that feels like it can’t exist anymore”

Being queer and Asian, living in a big city like Toronto has allowed Wei to find their sense of community. “We’re fighting so hard to be in these cities, because we just don’t feel comfortable living anywhere else,” said Wei. “I don’t really fit in a lot of places. I know I fit in Toronto, and I want to be able to live here.”

Zhixi Zhuang, an associate professor at the School of Urban and Regional Planning at Ryerson, said that cities have their own unique souls that are made up of the collective memories of the community.

“Your memories of the city give you a sense of belonging,” said Zhuang. When that’s taken away, she said that it can be tragic, especially for marginalized, underrepresented, and underprivileged community members.

“They have already been underprivileged, and they have never had their voices heard. And now that they have been displaced, they can be forgotten,” she said. “With this displacement, we’re destroying [the city’s] social fabrics and people’s connection to the community is broken.”

She acknowledges that cities require development if they anticipate growth, but with these new developments, cities should first think about who will be affected the most.

“I’m fascinated by how we build our cities and who we’re building them for, and wanted to explore the line between preserving the parts of our cities that make them special while creating new spaces, since we’re in the middle of a housing crisis,” wrote Wei in an email.

Deborah Cowen, a professor from the University of Toronto featured in the film, said that means almost 90 per cent of the development won’t be affordable—Westbank originally received $18.75 million in government funding for 85 affordable housing units out of 800. Cowen said another problem is that affordable housing is being defined in relation to average market rents, not in relation to people’s incomes, like in many other major cities.

Wei hopes that their film will start conversations around affordable housing and encourage people to organize in favour of affordable housing.

“It’s amazing that [Mirvish Village] existed. It gave a lot of opportunities for different artists, and it had cheaper rents. And I think that’s really rare for Toronto these days,” said Wei.

There’s No Place Like This Place, Anywhere will premiere on CBC on Oct. 8 at 8pm.

Leave a Reply