The process behind scholarships can harm those who need them most

Words by Edward Djan

Visuals by Jes Mason and Vanessa Kauk

Near the end of the fall 2019 semester, Iman Ayla* sat at her desk in her studio apartment in Toronto after finishing up some household chores. It was a gloomy December afternoon when her phone suddenly rang. When she picked up the call, she was told her father had been diagnosed with cancer. Immediately, fear started to settle in as she grappled with the possibility of losing her father while being 11,000 miles away from home.

Not wanting to be away from her father during this time, Ayla tried to book a flight to see him at an overseas hospital, slowly feeling more and more hopeless as she tried to find plane tickets. After two weeks of searching, she finally found one and hastily made plans to leave the country.

However, the reality of Ayla’s studies quickly seeped in. She was enrolled in four courses at the time and was able to complete two of them before travelling.

Ayla saw her father before he was admitted to the hospital for nearly a month-long stay for his cancer treatment. During this time, Ayla discovered he was a lot sicker than she initially thought. At one point, doctors thought they might have had to transfer him to the Intensive Care Unit. “It was a very hard time,” says Ayla. “It was a lot of stress, a lot of fear of losing him, a lot of sorrow, a lot of mixture of emotions and it kept changing every day.”

Three months later in March 2020, COVID-19 started to spread worldwide and countries began closing their borders. Due to travel restrictions, Ayla was unable to return back to Toronto to complete her exams and ended up failing her other two courses. She decided to take the winter 2020 term off school, instead choosing to spend more time with her father and family.

At that point, she wanted to drop her remaining courses because the environment she was in made it difficult for her to continue with her coursework. Since the semester was almost done, the deadline to drop courses had long passed, but school administrators offered a three-month extension to complete her exams.

Not wanting to burden her family with more expenses, Ayla feels the need to find more money to pay for her education herself. But unlike others, Ayla is unable to work due to her disability. “It was hard for me to manage schoolwork and out-of-school work since my disability slows me down.”

Prior to her father’s hospitalization, her family had been helping to pay for her education. However, the new costs associated with his immunotherapy, such as medications and accommodations for the family to be near the hospital, made it difficult for them to continue contributing.

Ayla thus relies on applying to financial scholarships. Yet, when asked to detail in scholarship applications examples in her life where she’s had to overcome hardships, she steers clear of this story. Ayla believes she’s more than a trauma story, and because of that, avoids applying to scholarships that ask her to reveal sensitive details about her life.

“When you talk about your challenges, when you talk about your disabilities, you’re always talking about your limitations,” she says. “You’re not talking about how empowered you are, you’re not talking about your successes.”

Applying for scholarships is a necessity for many students pursuing post-secondary education. Often, before students decide on a school they want to attend, they’re told by high school teachers, guidance counsellors and school brochures to apply for scholarships to fund their post-secondary education.

For racialized students especially, there is an added barrier to accessing education. Rai Reece, a sociology professor at Ryerson University, says the social-economic position of racialized people in our society—for example, the high rates of poverty and the “ghettoization” of racialized people into certain jobs like domestic work—positions them without access to wealth. This in turn impacts their access to education.

In Canada, the average national cost of undergraduate tuition for the 2021-22 school year is $6,693 for domestic students and $33,623 for international students, according to Statistics Canada. In Ontario, those costs are even higher, with domestic undergraduate students slated to pay on average $7,938 while international students pay on average $42,185.

Post-secondary institutions also rely more on tuition fees for revenue as provinces reduce funding to schools, with financial support from fees increased from $6.9 billion to $9 billion in the 2013-14 school year. In 2019, Ontario also reduced financial support from the Ontario Student Assistance Program, slashing the family income threshold from $175,000 to $140,000.

With provincial cuts and hikes in tuition, many students rely on scholarships in order to pay for school. A 2015 survey by Statistics Canada found that 56 per cent of university graduates in Canada relied on some form of monetary support, including scholarships, to finance a portion or all of their tuition fees.

“Scholarships can play an important role in supporting education for racialized students,” says Reece. But she says creating scholarships that are accessible and reflect the social position of these students is equally important.

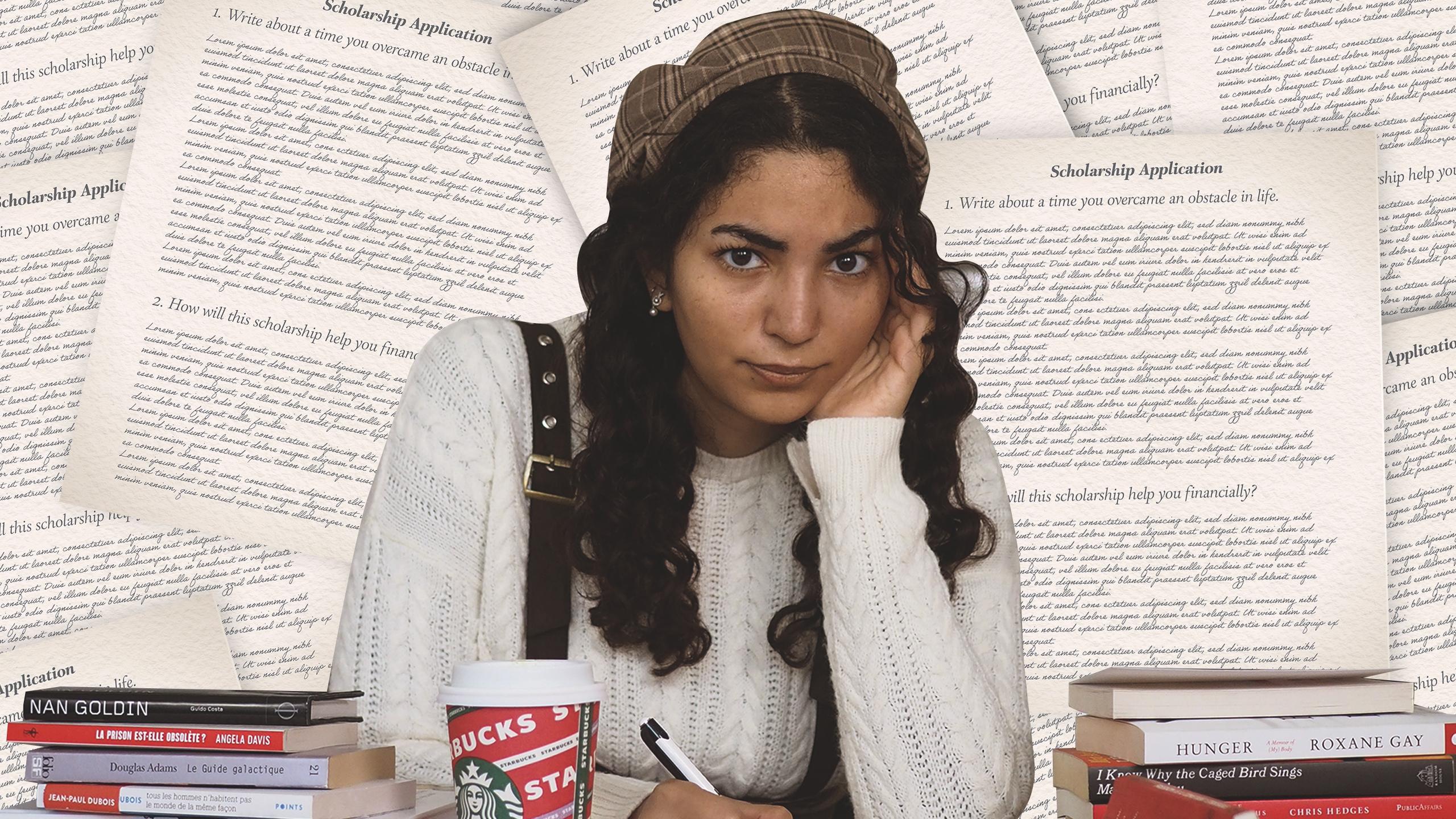

However, when applying for scholarships, students are often met with a laundry list of conditions that include proving financial need, outlining extracurricular activities, providing transcripts of academic performance and detailing traumatic or sensitive life events. Students like Ayla report spending hours applying for scholarships where they’re expected to put their lives—including their schoolwork—on hold for a chance to be awarded small amounts of money that cover fractions of their tuition fees.

The added financial burden along with the daily responsibilities and worries of being a student can cause enormous amounts of stress, according to Hamilton-based psychotherapist Carly Fleming.

Scholarship applications that ask students to detail their trauma can cause more harm than good, she explains. “We know that retelling a story of trauma can be retraumatizing,” says Fleming. She explains that when you retell a story in the right context, for example, to someone who is trauma-informed and sensitive, it can be healing—but context is everything.

“When we take away the sensitivity of the recipient of the story, there’s no doubt that it can be retraumatizing,” says Fleming. “It can bring things up that are very painful and then leave the student without appropriate support to then figure out how to manage that.”

t was the end of the day on a fall evening in 2019 when An Kun* finished her school work, putting away her books for the night. It was now midnight and the then first-year human resources management student decided to scroll through AwardSpring, Ryerson’s central scholarship application website, looking for scholarships to apply for.

As she looked through what she had to do, she realized it was the middle of October and application deadlines were just around the corner. This prompted Kun to open up a scholarship application she’d been procrastinating for about two weeks. As she went through the scholarship’s requirements in order to prepare what she had to write, she found herself rubbing the palm of her hand against her cheeks and chin.

She says it was a coping mechanism she used to get through the application. “I was distracting myself so that I wouldn’t feel the emotion part of it while I was writing, because it was a sensitive topic,” she says. “I knew I had to finish the essay but at the same time, I didn’t want to cause a breakdown for myself.”

The application asked for personal or mental health struggles experienced by students during their studies and how applicants “overcome those challenges,” says Kun. Now in third year, she describes herself as being usually reserved, not often revealing personal details about herself to others.

“I want the things that are closest to my heart to remain hidden,” she says. She doesn’t feel comfortable sharing her personal experiences, especially those that she feels could hurt her. “As an individual, I just don’t want to show my weaknesses.”

Even though she was uncomfortable, Kun continued the application because the funding from it would have helped relieve her parents of the financial burdens of paying for her studies. Ultimately, Kun decided to write about how she was taking care of her mental health while processing the death of her father and helping her mother after she was sexually assaulted.

Kun thought if she put the extra effort into writing the 500-word essay for the scholarship application, it would differentiate her from other applicants. She continued this process, while experiencing a great deal of emotion, for about two weeks before submitting her application, hopeful that she would get it.

Despite all her hard work, Kun was not awarded the scholarship. She realized she spent all that time and effort, and most importantly, revealed information that she wouldn’t even tell her friends, on an application for a scholarship she didn’t receive. Kun was crushed; it was an intrusive process that she thought would eventually benefit and help fund her education.

“I didn’t get it in the end, so I was disappointed, of course. It discouraged me so I didn’t apply for any scholarships in second year,” Kun said. She says it’s also difficult when you don’t know who’s on the receiving end of the application. “We have no idea who’s looking at them or who’s reading them, it does feel a bit invasive,” she says. “Someone knows my story out there and it’s just uncomfortable.”

Reece says this process is incredibly harmful. “Putting a premium and value on whether or not someone is worthy of a scholarship based on retelling trauma is a form of violence.”

Reece explains that asking students to retell traumatic experiences without providing a platform of care for that retelling is irresponsible and doesn’t demonstrate an ethic of care. “What happens to the student who bears their pain and then doesn’t receive the scholarship? They are left to sift through the residual impact of that truth-telling endeavour by themselves,” she says.

Reece also asks why it’s deemed necessary to exploit pain for profit and where the validity of that pain will be measured. “This line of reasoning is fundamentally flawed.”

Kun feels it isn’t completely ethical for the school to be asking for this kind of personal information. She adds that the school probably receives these types of trauma-based stories from hundreds of students in scholarship applications and is unsettled by how the committee has the right to validate and invalidate certain experiences.

“They just break these kids’ hearts and they’re probably in financial need as well.”

Kun now only applies to merit-based scholarships that ask about extracurricular activities and academic performance, even though they require her to spend her spare time with various campus groups and volunteer organizations. That way, at least if she doesn’t win a scholarship, she doesn’t have to reveal personal information to people she’s uncomfortable sharing it with.

Merit-based scholarships are financial awards based on academic or extracurricular performance rather than personal struggles. While these scholarships don’t require students to reveal information they’re not ready to tell, they require students to spend copious amounts of time on extracurricular activities while dealing with the stress of trying to maintain high GPAs.

In Tennessee, 84 per cent of merit-based scholarship recipients were white, even though they only made up 72 per cent of the college population in the state, according to the Wall Street Journal.

While Kun, like some other racialized and marginalized students, may prefer merit-based scholarships, research from the United States shows that white students benefit from them the most.

A study into merit-based scholarships by Harvard University also found that white students benefited from these scholarships disproportionately more than racialized students in Alaska, Florida, Kentucky, Michigan and New Mexico.

Instead of relying solely on merit, the study recommends adding financial need as a requirement onto merit-based scholarships in order to ensure that students in need are able to receive funding.

“Currently, the non-need, merit-based scholarship programs are not increasing access to higher education for minorities and high poverty students,” the study says. It adds that this results in fewer opportunities for those students, economically and socially.

Kun also acknowledges the limitations of merit-based scholarships and the effects that they can have on racialized students. She says these limitations can come from cultural differences. For example, she explains that in traditional East-Asian families, there is a heavy focus on high grades and a lot of this comes from parental pressure. Kun says this can discourage a lot of students in similar situations from participating in extracurricular activities because they prioritize higher grades. “In those cases, their culture just doesn’t allow them to qualify for these merit awards in the first place,” Kun says.

Despite this barrier, Kun, who now has won scholarships based on extracurricular involvement this year, believes merit-based scholarships are still better than ones based on an applicant’s trauma because at least Kun knows she’s being rewarded for her leadership. “But if it was with mental health, am I just being rewarded for having the saddest story out there? It wouldn’t have made me happy,” Kun says.

At least when she applies to merit-based scholarships, Kun knows she’s being rewarded for her leadership. “But if it was with mental health, am I just being rewarded for having the saddest story out there? It wouldn’t have made me happy,” Kun says.

“Receiving those scholarships made me realize I really don’t like that idea of having to sell our experiences out there for the money.”

nce her father’s condition started to improve, Ayla moved back to Toronto and enrolled in summer courses, in which she excelled. Due to her performance, her GPA improved, which made her eligible to apply for more scholarships to offset the costs of her education.

However, she believes the scholarship application should be overhauled.

Rather than scholarship applications asking for grades or personal trauma, Ayla wants to see more questions about students’ personal development and how they’ve improved in areas such as mental health or emotional intelligence. She wants scholarship applications to put student experiences in a more positive light—where growth in personal relationships, life and spirituality are highlighted, as opposed to suffering.

“We really need to see how a student has managed to evolve themself in many areas,” Ayla says. “That’s not there in many scholarships.”

*Names have been changed to protect sources’ privacy and security

With files from Abeer Khan

Paul Gilbert

Your title / focus on the article is ABLEIST As while the article itself focuses on ““When you talk about your challenges, when you talk about your disabilities, you’re always talking about your limitations,” she says. “You’re not talking about how empowered you are, you’re not talking about your successes.” But, you’re only highlighting how this impacts on BIPOC students? Do you hate the disabled so much that you need to erase us?

Amanda Lang

This article highlights just a few of the countless reasons why we should have universal post-secondary in Canada. The debt model is a gargantuan barrier. As much as scholarships and awards are intended to improve access, in effect they are part of the gatekeeping. The mental effort, emotional effort, and time needed to complete these applications is an added burden on the students whose capacity is already stretched thinnest and who most need assistance instead of hurdles. It also puts students in the worst kind of competition with each other – vying to see whose struggles are the most enticing to those holding the purse-strings. For those who don’t qualify / don’t have the capacity to apply / are not comfortable detailing their challenges or justifying themselves / who have been rejected / etc., this “assistance” is largely inaccessible. To add insult to injury, students repeatedly receive emails enjoining them to apply because there’s “so much money sitting on the table”. It doesn’t feel that way. If we want a society in which people have access to an education, we need to make education truly accessible.