By Samira Balsara

Although Ryerson currently has no plans in place to divest from all fossil fuels, president Mohamed Lachemi said the university is working with investment management companies to integrate environmental considerations into its investments.

Following the University of Toronto’s announcement on Oct. 27 that it would be divesting from all fossil fuels by 2030, Lachemi told The Eyeopener that there are no tangible plans yet for the school to do the same.

While he noted that the university is “continuously taking steps to responsibly address the climate change challenge,” a solid plan to divest from fossil fuels is not yet on the agenda.

Lachemi said many universities that have chosen divestment have multiple investment managers with committees who actively make decisions about asset mix strategies.

He said Ryerson only has two investment managers: Fiera Capital Corporation, which deals with the university’s endowment—the sum of assets invested by a college or university to support its education and research—and Opus Asset Management, which handles its pension.

“So this active investment activity is not a regular occurrence at Ryerson,” he said.

Nevertheless, the university’s endowment is invested through an “environmental, social and governance” approach.

“Fiera integrates environmental, social and governance considerations into the investment process of each investment strategy,” he said, adding that such considerations involve evaluating whether a company demonstrates efforts to reduce its environmental footprint.

“The fossil fuel industry is one of the main barriers to action on climate change”

Fossil Free Ryerson, a student-led grassroots organization founded by former Board of Governors student representative MJ Wright, stated that the university currently invests $17.5 million in the fossil fuel industry, which makes up 12.4 per cent of the endowment fund. Some of the companies the school invests in are Suncor Energy Inc. and Pembina Pipeline.

The university also recently joined the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative, an international group of asset managers committed to supporting the goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 or sooner, according to Lachemi.

He added that the university is planning on joining the University Network for Investor Engagement (UNIE), a coalition of Canadian university endowments and pension plans that aims to leverage the collective power of institutional investors to address climate change risks in their investment portfolios.

But the fossil fuel industry remains a pressing issue worldwide when it comes to climate change.

“The fossil fuel industry is one of the main barriers to action on climate change, and it’s been that way for several decades,” said Michelle Marcus, a divestment organizer with Climate Justice UBC, a political climate action group at the University of British Columbia, and the Divest Canada Coalition.

“Schools that have committed to divestment have had a very active student movement”

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 89 per cent of global CO2 emissions in 2018 came from fossil fuels and the larger industry.

An article from NPR reported that since 2011, the movement to divest in fossil fuels has mainly been a student-led movement.

Evelyn Austin, a recent U of T graduate, project manager for the Banking on a Better Future campaign and coordinator for the Divest Canada Coalition, said the movement has started to pick up in the U.S. and U.K. She noted Canada has been lagging but U of T’s divestment will bring about changes in the country.

When it comes to U of T’s divestment move, Austin described it as “a whole long history.”

She said the momentum started to pick up in 2013 with a petition that got thousands of signatures, but the latest announcement was a bit of a shock to some.

“When it comes to the divestment commitment, that really took us by surprise, none of us knew that was coming. They didn’t tell us in advance,” Austin said.

She said Harvard University’s divestment announcement in September may have influenced U of T.

While the announcement was surprising, Marcus and Austin both said they see this latest move as a step in the right direction.

Austin said U of T’s announcement will make a big impact because the school is of a high social status and has the largest endowment in Canada—$3.15 billion according to the university’s 2021 financial report.

When it comes to steps Ryerson could take toward divesting, Christopher Gore, a professor in the Department of Politics and Public Administration and a member of the school’s Climate and Energy Working Group, said the university needs to be transparent.

“The tricky thing for Ryerson is that its trusts and endowment is not high, compared to a place like U of T. The policies and rules guiding university investing need to be reviewed and clarified, and should state explicitly where climate change fits into this,” he said.

But Austin added that this needs to be a student-led movement and no change will come without pressure from students and staff.

“Pretty much all the schools that have committed to divestment have had a very, very active student movement. What it’s going to take for Ryerson is pressure,” Marcus said.

Austin added that a presence of some kind constantly drawing attention to the issue is necessary.

“Remember that divestment is very political,” she said. “And so it sort of takes a political effort in that way, on behalf of students or faculty organizing,” she said.

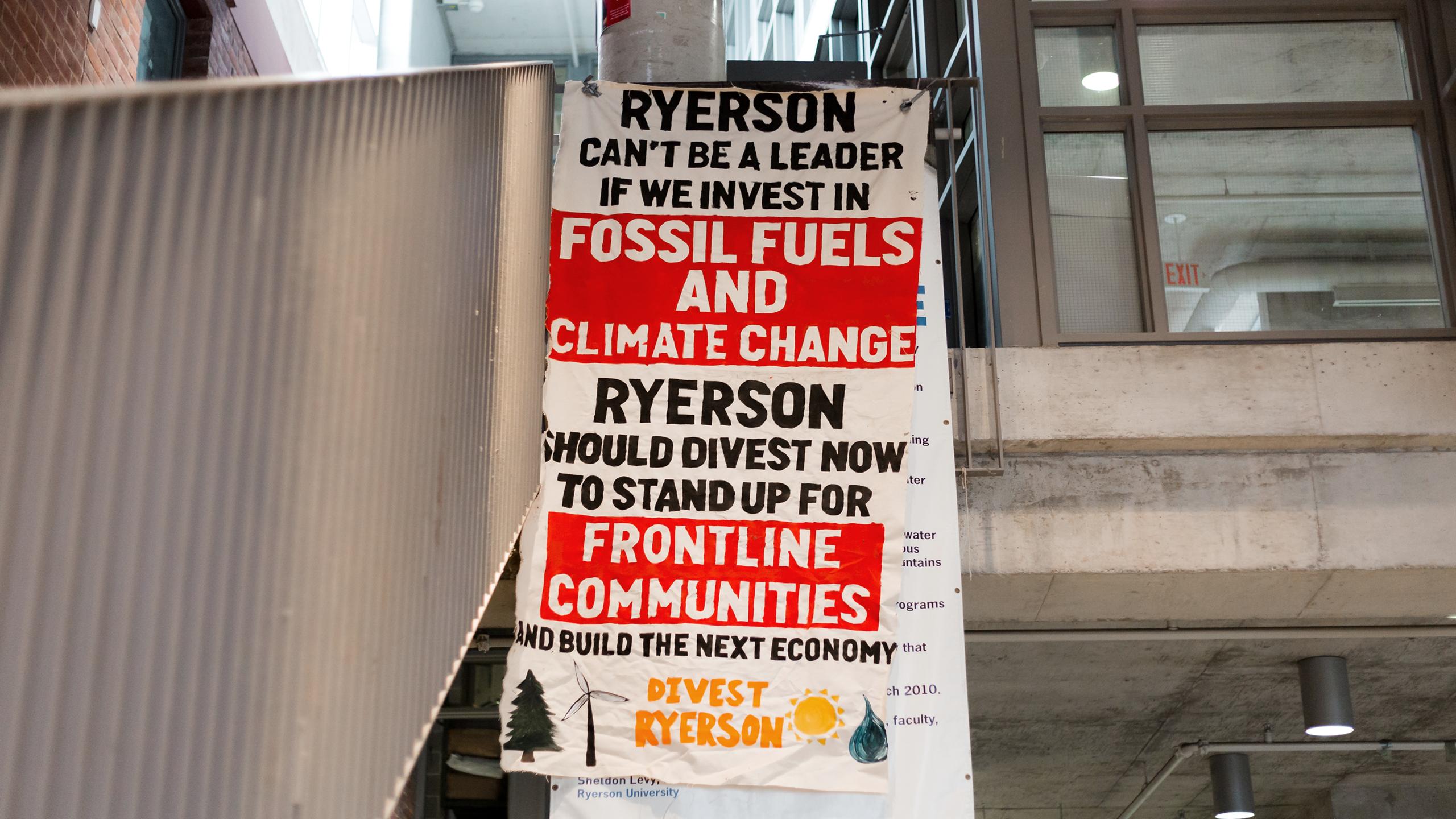

Although the Divest Ryerson group has had minimal activity in the past five years, Fossil Free Ryerson started a petition in March 2020, calling on students on social media to sign it.

According to Gore, Ryerson claims to be an “innovative space to learn” and also claims to champion sustainability. He said the university will not benefit from hiding or failing to address the debate about divestment and fossil fuels.

“Ryerson leadership needs to articulate a clear position on divestment or establish a process for evaluating its future position in relation to fossil fuel investments because the pressure to account for its actions will not go away and the need to respond is high.”

Marcus echoed this and said she thinks divesting from fossil fuels is the right decision for schools and should be a change that universities start to implement.

“Originally with the movement, universities were scared of making this decision because they thought it could tarnish their reputation or relationships with donors,” she said.

“But I think more and more, it’s going to be the opposite where the universities that don’t divest are going to have this reputational risk and it’s just going to look really embarrassing for them.”

With files from Heidi Lee

A previous version of this story stated Michelle Marcus is a divestment organizer for the Climate Justice Series, when in fact she’s a divestment organizer at Climate Justice UBC. The Eyeopener regrets this error.

Leave a Reply