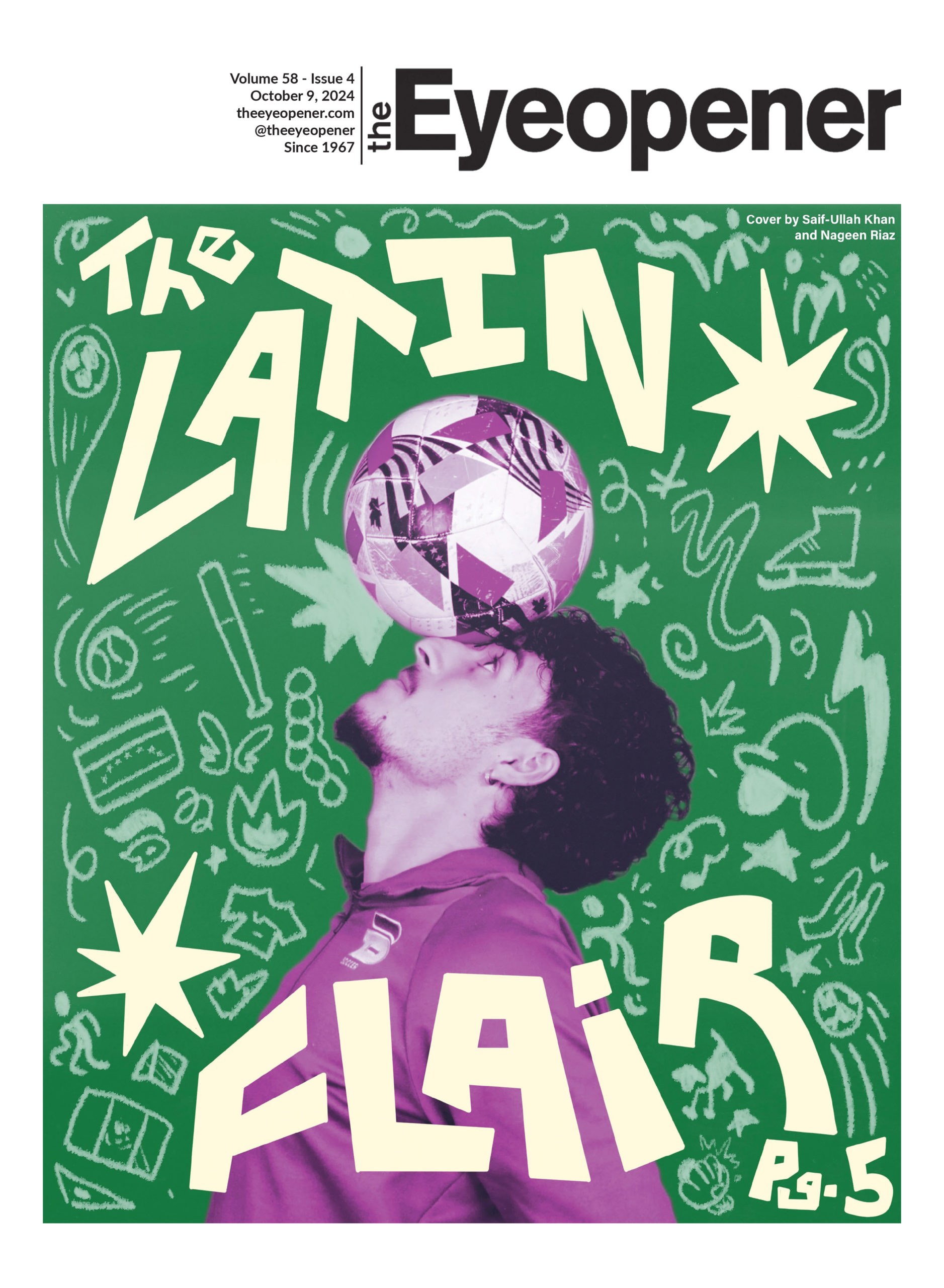

how TMU students are reclaiming their hometown pride in the face of stereotypes

Words by Rochelle Raveendran

Visuals by Jes Mason

Photo by Alicia Reid

On a spring day in 2021, Amreen Kullar strolled around the Toronto Ontario Temple—also known as the Latter-day Saints Temple—in Brampton, Ont. She spent two hours taking photographs of the stark white building with her trusty pocket-sized Nikon 35mm camera. The temple is close enough to her home that she can spot the towering spire from her bedroom window, topped with a gilded statue of the angel Moroni.

Photography was a favourite travel pastime of Kullar’s, but after the COVID-19 pandemic grounded her in her hometown of Brampton, she decided to point the camera to places in her neighbourhood that were already imprinted in her memory. Other subjects Kullar photographed included the library she used to visit with her father, who immigrated to the city from India in the ‘90s, and the SilverCity theatre that helped shape her love of cinema.

The resulting photographs formed the visuals for her photo essay, Brampton in the Winter—saturated with nostalgia and accompanied by a punchy spoken word piece that denounced derogatory assumptions aimed at the city and its residents. Visible minorities make up 73 per cent of Brampton’s population, according to census data from 2016. Nicknames given to Brampton by people in and around the Greater Toronto Area, like “Browntown’’ and “Bramladesh,” deride the city’s large South Asian population. In her piece, Kullar flips mockery of the city as an ethnic enclave on its head, making Brampton synonymous with bravery. “In Brampton,” she writes in her piece, “we resist.”

Kullar, a filmmaker who graduated from Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) in 2021, wasn’t always affectionate toward her hometown; dislike for Brampton was deeply entrenched in her high school experience. She recalls longing to move away for university and days when she thought being called “whitewashed” was a compliment. It was only after Kullar began attending TMU’s media production program that she realised how much of a gift it was to grow up in a community with shared cultural touchpoints. When she’d tell people in Toronto where she was from, responses ranged from assumptions of the city’s inherent inferiority, to uncertainty of how to react, to ‘Of course you’re from Brampton.’

“Even if you don’t live [in Brampton] and you just say that you’re from there, it’s automatically like a roast,” Kullar says.

Media coverage of Brampton’s pandemic response heightened her accumulated frustrations. Kullar notes positivity rates were blamed on cultural celebrations like Diwali, rather than the lack of protections for essential factory workers. Brampton also faced disparities in the rollout of vaccines and a longstanding underfunded healthcare system—equity issues also felt in Scarborough, Ont., where 73 per cent of the population are also visible minorities.

For Kullar, Brampton in the Winter was an assertion of hometown pride at a time when her city was facing waves of racist scrutiny. She describes a “heartwarming” response to her photo essay; her comments were flooded with other locals vocalizing their own frustrations, alongside their love for Brampton. People from Scarborough and other GTA suburbs expressed similar sentiments for their own cities. If even a single person comes away from her work feeling proud of their hometown or deciding to take an extra second before cringing at the mere mention of Brampton’s name, Kullar will be satisfied.

“What matters to me is changing tiny universes.”

n the ‘majority-minority’ cities of Brampton and Scarborough, where racialized people form the majority of the population, artists and filmmakers are denouncing negative preconceptions about their cities through their storytelling. TMU students and alumni are using their poetry, photography and videography to reclaim narratives in the public imagination about their hometowns, countering stereotypes through art informed by their own authentic experiences.

Min Sook Lee, a documentary filmmaker and assistant professor at OCAD University, says for too long the arts have been dominated by a homogeneous group of people who held the mantle of storytelling power—particularly straight white men. The language of reclaiming “contextualizes the act of representation,” she says, while also recognizing that marginalized people have always been storytellers in their own communities.

Lee describes art as essential to social change; dismissing it as frivolous or simply decoration is misguided and troubling. “Cultural work is where social transformative change happens first, because you have to imagine the world you want to live in, in order to move towards building it,” she says. The arts provide opportunities for dialogue and discussion amongst people with diverse beliefs, according to an article in Psych journal. Consequently, it can be a means of raising public consciousness within communities, encouraging them to press for social change.

Scarborough-based singer and poet, Shadel Chavez, says art has the power to rebuild and strengthen. Chavez has been active in the local arts scene for over ten years and compares art to medicine, especially within RISE Edutainment, a Scarborough-based arts organization that seeks to provide an inclusive space for young and emerging artists.

Art is a universal language, Chavez says. “People who feel called to share have a place to speak uninterrupted, in as loud or as subtle forms as they wish. Their art can be a mirror for anyone that encounters it…and it can be a ripple effect of introspection and positive change.”

Kullar has a personal understanding of storytelling’s transformative power. She decided to become a filmmaker after experiencing firsthand how makes viewers more empathetic towards others’ perspectives. Rather than placing blame on specific individuals for their prejudices, Kullar prefers a creative intention that shows people a different way to think.

“The way your emotions and vulnerability come out in pieces of work makes people rethink their stances [and] what they say, and allows them to have more empathy,” she says.

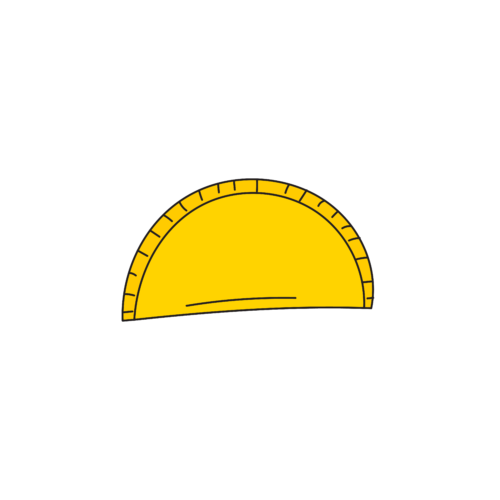

arden Station isn’t a needed stop on photographer and filmmaker Alicia Reid’s typical commute. She mainly finds herself there when she wants to pick up a Fahmee Bakery patty sold at the station, a detour on her commute to TMU from her hometown of Scarborough. The debate over which subway station sells the best patty is a heated and passionate one in the city. But for Reid, there’s no question that Warden Station surpasses all others—an opinion that would eventually guide her in her artistic documentation of the borough.

In the months following the onset of the pandemic, Reid found herself in a tailspin. Reid, who graduated from the journalism program in 2022, was no longer regularly commuting downtown for school and work, which shifted her artistic inspirations. Much of Reid’s early photography revolved around documenting downtown Toronto. She particularly gravitated towards hotspots like the Rogers Centre and Harbourfront, which were often featured on local sites like Narcity Toronto and blogTO. The events and concerts she typically photographed had also shut down, including the Toronto Caribbean Carnival, which resumed in 2022 following a two-year hiatus. This abrupt absence of her typical subjects led Reid to question whether she could still see herself pursuing a career in photography.

As she pondered her creative future, Reid came across Scarborough’s New View, a photography contest by the City of Toronto and Scarborough Arts, in August 2020. According to the contest website, it intended to create a “new, more accurate narrative” about the borough and its residents. The contest was a response to the discovery that the first result on Google Images when searching up Scarborough was a photograph of a collapsed home. Outside of computer algorithms, Reid has witnessed her share of limited, often racist, views about her hometown, including descriptions of it being a “ghetto” and a crime-riddled place.

With her Canon DSLR and new inspiration in hand, the contest propelled Reid throughout her neighbourhood over the course of September 2021, from the Scarborough Bluffs to Thomson Memorial Park. When it came to the contest category “Things,” Reid intrinsically knew the one object that could represent both the food culture that embodies Scarborough and the importance of a transit system that’s as much used by locals as it is maligned by them. She stood on a Warden Station platform, held up a patty with a fresh white manicure and took the shot. The result was Warden Station Patty, which made Reid one of three Grand Prize winners in a contest that received over 3,700 submissions.

She describes her win as a shocking and affirming experience. Reid had found a new muse, the beautifully dynamic and diverse borough that she’s proud to call her home. In the process, she had also found a renewed sense of purpose. She simultaneously shot video footage on her phone for what would become STARBOROUGH, a personal video project and short ode to her home that includes clips of the Scarborough Town Centre and Scarborough General Hospital.

“This is what I’m meant to be doing,” Reid says. “I’m meant to be highlighting and uplifting my community.” For out-of-towners who see her work, she hopes they will question their prejudices about Scarborough and consider visiting.

Both Scarborough residents and visitors can view Reid’s Warden Station Patty as part of a new display in the Scarborough Museum, which features rotating pieces by local artists. Historical interpreter Faith Rajasingham worked with her team to develop the exhibit and content.

She says this is part of a transitional process by the Toronto History Museums collective to move away from primarily telling white settler histories. This narrow focus “absolutely didn’t do any justice to the history or community of Scarborough,” Rajasingham says, as it didn’t reflect the diversity of locals. Of the largest visible minority groups in the borough, 25 per cent of residents identify as South Asian, nine per cent as Black and 12 per cent as Filipino.

In the 19th century farmhouse Cornell House, one of four heritage buildings that compose the museum, a portrait of Queen Victoria and a photograph of Westminster Abbey were taken down to display six pieces, including Warden Station Patty.

Rajasingham, who was born and raised in Scarborough, says locals have had an overwhelmingly positive response to the new display since it launched last December. In her role as a tour guide, she says visitors from the borough almost do her job for her when they see Reid’s photograph; there’s an immediate understanding of how the Toronto patty debate ties into Scarborough’s identity.

“Having these art pieces on the wall is reclaiming these spaces, asserting our histories and our presence and saying that we belong here, too,” Rajasingham says.

In community spaces like RISE, Chavez likens herself and her fellow artists to seeds being nurtured by local mentors in art, including Randell Adjei, the founder of RISE and Ontario’s first poet laureate. She aspires to do the same for others, particularly fellow Filipino artists in Scarborough. “I have been thinking about how I am tomorrow’s ancestor with every project I am involved in,” she says.

As Reid continues developing in her photography and videography journey, she does so with the understanding that she wants people to feel proud about where they come from. Her photography was recently featured in Scarborough Made Resilience, a public art installation outside Cedarbrae Library, that highlights the stories of community leaders. Reid’s creative work brings her joy when she’s able to show people a side to her beloved borough they may have never seen.

“There’s a kind of underdog persona that’s wrapped around with Scarborough…but I’m tired of being the underdog,” she says. “I want to be a champion in my own way for my community.”

fter Kullar posted Brampton in the Winter on her Instagram page, the overwhelming social media response included messages from fellow artists. One user wrote that she had encouraged them to create a similar piece and another told her of their own writings about Brampton.

Brampton’s wealth of diversity informs the unique perspective of local arts, says Nuvi Sidhu, the chair of the advisory committee for the Arts, Culture & Creative Industry Development Agency, which advocates and provides programming for Brampton artists. She says funding for community artists is vital, as art is what everyone uses to survive. Sidhu is excited to hear local artists talk about the need to reclaim Brampton with a new narrative that reflects the city’s beauty, in the face of out-of-towners and social media posts that treat Brampton like “the butt of a joke.”

“The best way to change someone’s mind is to make them feel something about what you’re creating,” she says.

Kullar hopes to continue to platform marginalized communities and show diverse depictions of Brown people in her work. Another Brampton-specific project she has on the backburner is a visual essay, layering archival footage of the city with VHS tapes from her childhood recorded by her father and her own photography of Brampton.

Her work emerges from a deeply personal vulnerability. After four Sikh factory workers were killed in a shooting in a FedEx warehouse in Indianapolis in April 2021, she was sobbing in her bedroom as she started writing a new piece. The result was Ode to Factory Workers, an angry spoken word reflection on Kullar’s grief and her evolving perception of her parents’ own factory jobs.

With Brampton in the Winter, she applied a similar authenticity, only photographing places with which she felt a personal connection. Kullar says she’s wary of inadvertently presenting herself as a spokesperson of such a large and varied community. In the comments of her Instagram post, one user asked why Kullar hadn’t included a photograph of downtown Brampton. This was an intentional exclusion, as she was not very familiar with the area.

Instead, Kullar recalls encouragingly replying to the comment: “You go to downtown Brampton and take that photo because I want to see it from your point of view.”

Leave a Reply