The last thing on an eight-year-old’s mind when they hug someone is that it’s scandalous or inappropriate. A hug is a hug—it’s a way to show affection for your loved ones. But when I met my uncle, a family friend, for the first time and reached for a hug, I was hastily pulled back by the arms, my aunt whispering for me to stop. Everyone stilled and when I looked up, my uncle was towering over me with distaste strewn across his face.

“Girls shouldn’t give hugs,” he said.

That moment is ingrained in my brain as the first time I realized being a girl in a many Muslim cultures, including my own Pakistani one, means my body and actions will be demeaned and sexualized for the rest of my life. Where men are propped up on a pedestal in our culture, women are expected to be quiet, sit still and cover up—there is no onus on the man to be respectful, ask for consent or be a decent human being. Of course, this does not extend to the religion of Islam as a whole but can be projected in many cultures and nations that emphasize Islam in their ways of life.

This creates the perfect storm for violence against women to occur—because women are always seen as the problem, never men. And being wrongfully seen as the problem can be fatally consequential.

This past week, the world erupted in protests sparked by the death of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish Iranian woman detained by morality police in Iran on Sept. 13, accused of violating the country’s conservative dress code. Since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Iranian women have been required to wear the hijab in public.

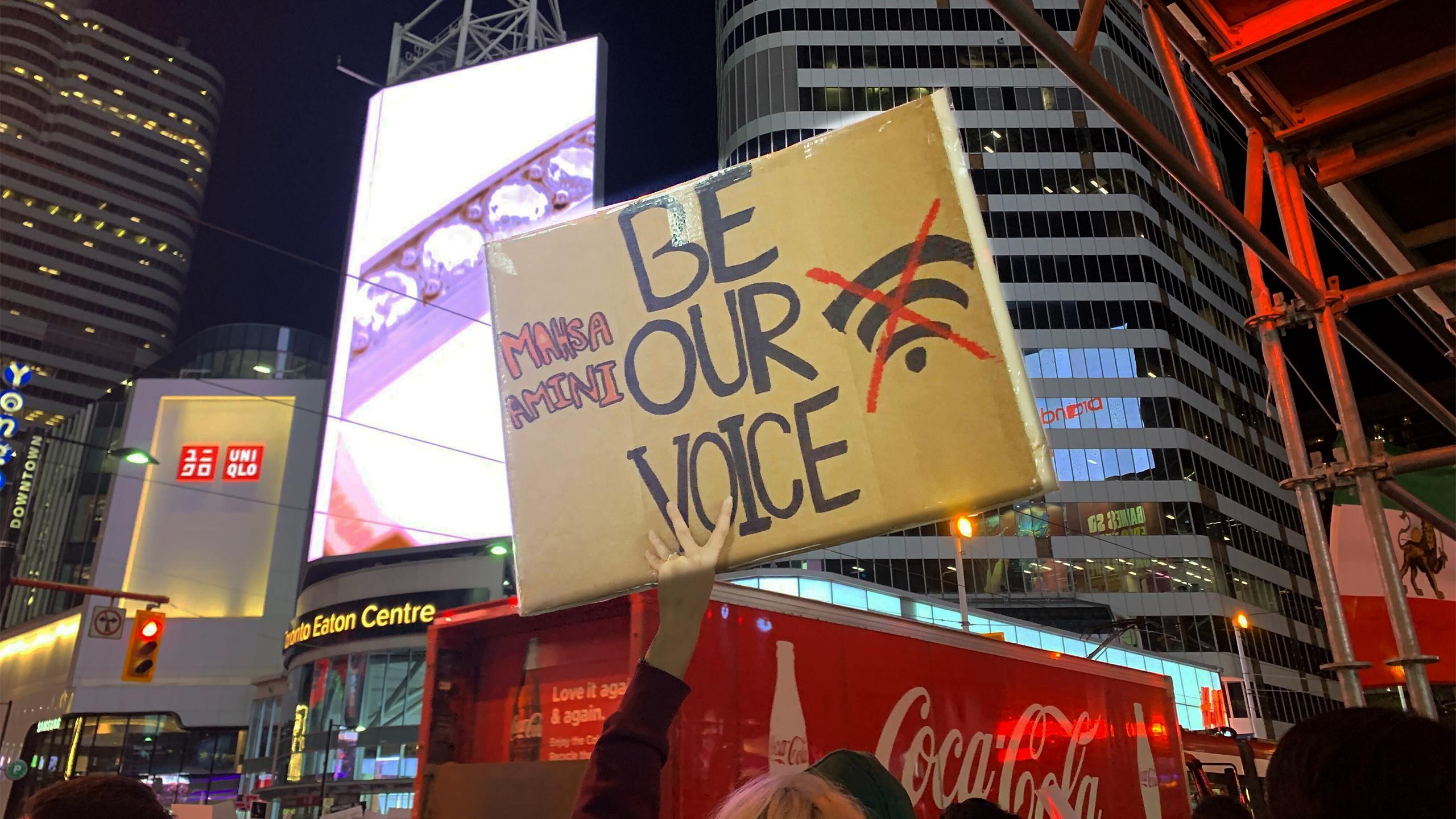

Currently in Iran, protesters have been organizing despite strict security forces, arrests and internet disruptions in the country following Mahsa’s death. Around the world, women and allies are marching in solidarity with the women of Iran and fighting for their right to choose, including in Toronto recently at Yonge-Dundas Square. On TikTok, women have shared how they are forced to cover up—with long pants, a compulsory head covering and a jacket overtop—when going out. There is no choice left in the way they choose to dress or practice their faith, it’s compulsory.

In a recent Toronto Star video, Iranian journalist and activist Masih Alinejad said many women in Iran relate with Mahsa’s story.

“They say that it feels like it could have happened to our daughters. It could have happened to us.”

Muslim women, in Iran and in many cultures around the world, fear abuse and death at the hands of those who wish to impose unjust religious expectations on their bodies. And this fear is justified because Mahsa’s case is not an isolated one—Muslim women constantly face violence within their communities. Just recently, Sania Khan, who was vocal on TikTok about her divorce, was allegedly murdered in Chicago by her ex-partner.

“Being wrongfully seen as the problem can be fatally consequential”

I was born in Toronto but I feel the impact of being a Muslim girl every day. Before I hit puberty, I was instructed to wear a scarf around my neck to cover my then-non-existent chest and was forbidden from wearing tight pants because they “accentuated my legs.”

Now, at 21, as a practicing hijabi, I understand these practices were a part of my family’s skewed attempt to uphold Islamic modesty, a concept derived from the Holy Quran, instructing women and men to lower their gaze. The Quran also instructs women to be mindful of their chastity, to not display their bodies in public and to wear a head covering.

In theory, the aim is for women to be empowered by covering their bodies so society sees them for more than their sexuality—it’s supposed to provide women with autonomy over their bodies.

Instead, the cultural perception of modesty imposed on me and other Muslim women has invited unwanted gazes, further sexualized our existence and invited harm onto our bodies, the complete opposite of its religious intention.

I wish I could go back and tell my eight-year-old self that what my aunt and uncle said to me that day wasn’t OK. I wish I could tell the Muslim girls who grew up like me, with older men and women constantly eyeing us up and down and making crude remarks about our bodies, that we are not the problem. I wish we lived in a world where women like Mahsa could wear what they want without the fear of being killed at the hands of an oppressive regime.

Until we break this cycle of patriarchy within our culture and understand that it is the woman’s right to choose whether she wants to wear a hijab or not, to cover up or not, gendered violence will continue to occur.

I urge all community members to stand in solidarity with Mahsa Amini and fight for the rights of women in Iran. Donate to organizations, spread the word and never forget what she died for: freedom of choice.

Leave a Reply