By Konnor Killoran

Pulling up to an unnamed bar on 1608 Queen St. W., a typically unassuming door had two things to indicate there may be some seismic energy afoot. A gaggle of smokers—maybe not dressed to match the typical patrons of the dive bar establishment—and a sign that read: Private event, no customers.

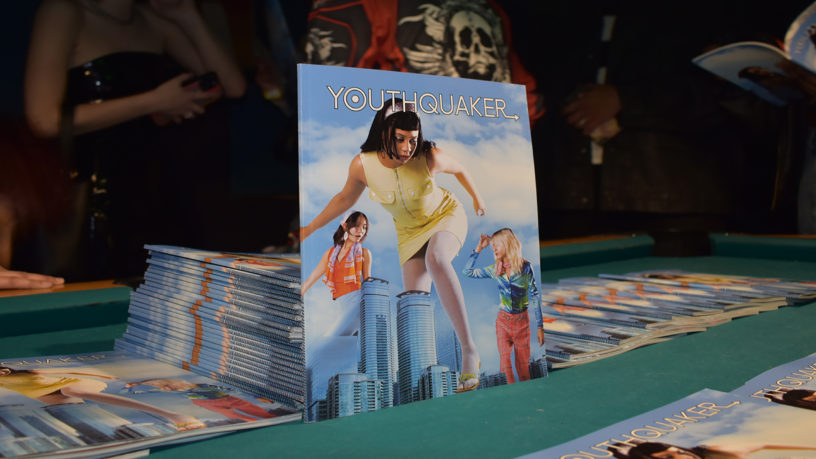

The aforementioned function was the first issue launch of Youthquaker, a new bimonthly print-only magazine focusing on youth culture that had the Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) campus buzzing.

The university’s newest publication is the brainchild of editor-in-chief Daisy Woelfling, a third-year creative industries student who said the idea came to her while driving back from her hometown of New York City.

“I was like, ‘You know what, I think now’s the time—if I want to go off on my own, this would be the time to start my own publication,’” said Woelfling.

Readers wouldn’t be surprised to learn then that the publication has connections to two iconic magazines that have shaped and critiqued culture for the past century.

The term “Youthquake” describes the 1960s youth movement, first coined by then-Vogue editor-in-chief Diana Vreeland. She described it as “youth culture at the time, bringing about transformative social change.”

In an interview at the publication’s launch event, Woelfling revealed the rest of the namesake’s inspiration: “We threw the ‘R’ on the end there [to] have it be ‘youthquaker,’ like The New Yorker.”

Dylan Bustos, creative director of the magazine, confirmed this by citing conversations he’d had with Woelfling—who’s also his roommate. Specifically, Bustos spoke about the lack of a modern monoculture—and by extension a dip in a firm “youth culture” compared to decades past.

“We wanted an outlet for people to be able to see what’s going on in culture, things that are usually not talked about in normal publications at [TMU],” said Bustos.

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines monoculture as “a culture dominated by a single element: a prevailing culture marked by homogeneity.”

“We want to go big and we don’t want to go home”

Picking up a copy of Youthquaker, readers are enveloped by that very nostalgic feeling the publication strives to encapsulate.

“One thing that we felt brought people together in the past was print,” said Bustos.

The decision to print stemmed from a longing for the medium. Both Woelfling and Bustos mentioned that there seems to be a pushback against the death of print media among Gen Z and saw Youthquaker as a way to revive the format.

“With so many publications out there having a digital component, I kind of wanted to do something to set us apart,” said Woelfling.

Bustos echoed this sentiment, believing that their release format is integral to building back community.

”You can’t get it online,” said Bustos. “So you have to come to the event, meet the people, learn about the concept and that way be more integrated with it.”

This physical exclusivity is what differentiates Youthquaker from other campus publications. With their first issue-launch event selling out online—it reaffirmed their belief. People even waited at the doors to get their hands on a limited number of first-come-first-serve tickets.

“We opened at 9 p.m. and there was a group of nine people standing outside asking me, ‘We don’t have tickets but we’d love to [purchase some],’” said Rachel Mandel, a creative industries student and events manager for Youthquaker.

Cracking open the magazine, there is social commentary, trend forecasts and everything else reminiscent of a pop culture magazine of the early 2000s.

From queer fashion to the “Reader’s Respite” among many other columns, it’s the talk of the generation, making Youthquaker an instant page-turner.

As for what’s next, the publication’s next issue is set to come out on Apr. 1, with an accompanying launch party to boot. Looking ahead, Mandel said:

“We want to go big and we don’t want to go home.”

Leave a Reply