Ryerson students with chronic disease say they’ve been ignored and mistreated by doctors while also having to fight for accomodations at school

Words by Sahara Mehdi

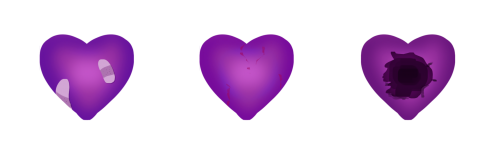

Visuals by Laila Amer

In the midst of the pandemic last winter, Meghan McCracken sat at her desk writing her midterm exam for her sociology course, SOC 112: The Social World. As she stared at her laptop, trying to decide between multiple-choice answers, the second-year social work student started to sweat. Then, nausea began to kick in along with a striking pain in her lower abdomen, which are common symptoms of her irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Since she had academic accommodations for her chronic disease, she took a break to use the bathroom, assuming she’d have enough time to finish the midterm when she returned. She hurried to the bathroom and sat down. A few moments later, she completely lost consciousness, then fell off the toilet.

McCracken awoke 45 seconds later, shot up and ran back to her computer, frantically clicking through the exam questions second-by-second. “I was too out of it to think,” she says. After submitting the exam, she contacted her professor right away to tell him she had just passed out and was going to the hospital. She also asked to retake the exam, to which the professor refused her request two days later.

McCracken then had to reach out to the head of the sociology department, who let her rewrite the exam after some convincing. Even though she finally received accommodation, she was angry at how much work it took to get them. She felt belittled by her professor, an older man in a position of authority who she felt couldn’t relate to the severity of her pain.

“I understand if you don’t want to believe me but I have a hospital band,” she recalls emailing him. “I’m sitting in the emergency room right now. I can provide as much proof as I can.”

A chronic disease is identified as any condition that lasts longer than six months and cannot be cured. Many chronic conditions are often invisible, and although there are treatments to alleviate some of its symptoms, they can never be completely healed. Young adults like McCracken who have been diagnosed with a chronic disease during university thus face a completely different post-secondary experience. Among the normal stressors of university life, these students struggle to feel understood by educators and doctors, which they say stems from the lack of knowledge and empathy people have regarding chronic diseases.

Sally Thorne, a nursing professor at the University of British Columbia, says there’s a social misconception that exists surrounding chronic diseases. She explains there’s a notion that if a person does excellent self-care, like eating or sleeping better, all of those things somehow would make their disease more manageable. However, she asserts that it’s not that simple. “Anybody with any kind of chronic condition knows that there is a level of self-care that can make a difference,” she says. “But by nature of it being chronic, there’s no one specific thing that will cure it.”

These misconceptions play a role in how students treat their conditions. They say they often feel the need to hide their challenges and persevere through pain without voicing their concerns or seeking accommodations for themselves.

“It’s different when you have a chronic illness because people don’t understand,” says Dr. Yvette Lu, a family physician based in Vancouver who wrote a research-based play titled Stories From The Closet: A Play About Living With Chronic Illness. She says most people experience acute illness, like the flu or a bad cough, but don’t really know what it’s like to live with a chronic illness that won’t disappear after just a couple of weeks.

This notion also trickles into Ontario’s healthcare system, where students say they’ve faced difficulty being taken seriously by professionals. According to a 2007 report from Ontario’s Ministry of Health, “Preventing and Managing Chronic Disease,” Ontario’s healthcare system was designed for acute illnesses instead of chronic diseases. Patients with chronic diseases are required to report to doctors when they have symptoms to have access to treatment. The report says this method is responsive and reactive, which is not ideal for the ongoing nature of chronic diseases. A proactive approach where patients could easily access a system to manage their condition would better suit people with chronic diseases, the report adds.

A study published by the Public Health Agency of Canada with data from 2015 to 2016 found that 44 per cent of Canadians over the age of 20 had at least one in 10 common chronic conditions. Despite this high percentage, students with chronic diseases say they often find themselves falling behind in university classes and feeling left out from campus life due to a lack of understanding from their peers and educators.

“I can’t go anywhere without feeling not well,” McCracken says. “Even going to school…I’m worried about what’s going to happen to my body. It’s embarrassing because fainting is not a nice thing, especially around people you might not know like my classmates. I’d be scared to faint because everybody would see me.”

ne Saturday morning, sixteen-year-old Margaret Walsh woke up feeling an excruciating pain in her right side. She was unable to move or even scream out for help. When she finally managed to get out of bed, she immediately ran to the bathroom, rushing to the toilet to vomit from the pain. Walsh’s mother heard her and came in to see what was wrong. Remembering that the appendix is on the right side of the body, her mother thought she might have appendicitis and she insisted they go to the emergency room right away.

Walsh was apprehensive about going to the hospital and angry at her mom for forcing her to go. She never felt heard or understood by healthcare professionals in the past and didn’t expect this time to be any different. “All my life, doctors told me that I wasn’t in pain and I had low pain tolerance,” Walsh says. After an entire day at the hospital, her fear of not being believed was confirmed when doctors sent her home, saying there was nothing wrong with her. She experienced the same pain the next month and was hospitalized again. Despite numerous tests, they still couldn’t find any results.

Five years after her first time being hospitalized, the now arts and contemporary studies student was finally diagnosed with low blood pressure in August 2021. At the time of her diagnosis, Walsh remembers her doctor rolling his eyes at her concerns and speaking exclusively to her mother despite Walsh being 21 years old. “It was just not a good experience when I got diagnosed,” she says. “It was terrible.”

She also asked her doctor to write a letter so she would be able to get accommodations at Ryerson, which he then discouraged. He said she didn’t need accommodations, because she doesn’t want pity.

Even though Walsh finally received an answer to years of pain and confusion, her initial excitement turned to discomfort as she tried to advocate for herself to a doctor who refused to listen. “I want help,” she says. “Yes, I can do it without help, but I don’t have to.”

This experience is not uncommon—many patients with a chronic disease struggle to receive an official diagnosis, a process that often involves misdiagnosis, disbelief and unempathetic doctors.

Dr. Lu says this is because physicians are sometimes unable to connect to or understand patients. “It might not be their fault,” she says. “But the way the system is structured, it sometimes doesn’t lend itself to a lot of empathy.”

She explains this is often due to doctors’ busy schedules that allow for only 10 to 15 minutes per patient, which in turn causes them to burn out. She says one solution to this problem would be to implement the study of narrative medicine in medical schools. According to a 2018 journal article in the Official Publication of The College of Family Physicians of Canada, narrative medicine uses stories to help doctors develop empathy for their patients, ideally resulting in better care. This technique uses art—such as films, plays or novels—to tell stories about living with difficult medical conditions.

The journal found that the “healing power of narrative is repeatedly attested to” but more research still needs to be done to scientifically prove its benefits. “When you watch a piece of art, it evokes emotions,” Dr. Lu says, explaining that emotions lead to empathy, which could help doctors better connect to their patients.

Walsh’s distrust of the healthcare system started when she was eight years old. She missed a day of school because she was suffering from severe leg pain that left her unable to walk. Her doctors told her it was just growing pains and that she was being dramatic, so she should ‘get over it.’ Another doctor she saw more recently told her she ‘must be bored’ and that she should ‘get out more’ in response to her pelvic pain.

“Being told that what I experienced is not real skewed my perception of life,” she says. Walsh also has family members who work in the medical field who have refused to believe her for as long as she can remember. When she was finally diagnosed, she decided not to tell them because she doesn’t want to go through the taxing process of convincing others that her pain is real.

“That’s not something that I’m interested in doing,” she says. “Why waste my time when I know it’s not gonna change anything?”

A 2019 study published in Health Care for Women International specifically looked at doctors treating patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Over 50 per cent of participants cited experiences with insensitive or disrespectful doctors, some of whom refused to test or treat the patient’s condition.

Thorne says there’s a lot of technical material to learn in medical school, which leaves little time to focus on the psychosocial aspects of caring for patients. “Unfortunately, there are some [doctors] who are good technicians of medical practice, but they’re not good at that emotional intelligence and human relational aspect of it.”

“I can’t live my life in pain,” Walsh says. She remembers struggling to maintain her 4.0 GPA in high school, completing her homework in bed during the four times she was hospitalized in Grade 12. “I have gotten better now at resting and not pushing myself to exhaustion, but sometimes, it can be really hard.”

n 2018, first-year student Kelsea MacKay’s dad dropped her off in front of the Ted Rogers School of Management building one hour before her final exam. She didn’t know what room her exam was in and the building was hard to navigate. She looked around and asked other students and staff for help, but nobody could offer assistance. As the clock kept ticking, she felt increasingly more stressed, causing her fibromyalgia to flare up. Typically, fibromyalgia causes pain in the muscles and soft tissues surrounding the joints, as well as excessive exhaustion. For MacKay, she also experiences migraines and stomach pains.

She eventually looked at the time and realized her exam had started 10 minutes ago, yet she still had no idea where to go. “I just sat down and cried because every muscle in my body hurt and I was sweating,” says MacKay, who is now a fifth-year media production student.

She ended up failing that course and the mark. This, combined with similar experiences in other classes, has left a lasting impact on her undergraduate career and hindered her from applying to a specific exchange course. Despite her explaining the reasons behind the drop in her GPA and showing external awards she’d won as proof of her professional caliber, a senior administrator in the media production department refused to make any exceptions, telling her she should retake courses instead.

MacKay says online school during the pandemic helped her realize how Ryerson could better accommodate students with chronic diseases. With a condition that causes chronic pain, MacKay can have trouble physically getting to school. Her hour-long commute involves standing for 10 to 20 minutes waiting for streetcars and a 10-minute walk to campus, which may sound simple to the average person but can be very challenging when compounded with her fibromyalgia symptoms. She says when school was in person, she was unable to receive an accommodation for days when her pain prevented her from attending class, but the school offered to give her extra time for assignments. However, MacKay says this wasn’t enough help because if she’s unable to be at school, she doesn’t know what she’s missing and can’t complete an assignment without that crucial context.

She says Ryerson should make it mandatory for all lectures to be recorded and posted for students to watch, as many online classes have been during the pandemic. “It’s really ableist when the teachers say if you’re not in class, you don’t get to see what was in class,” she says.

MacKay adds that she pays to attend the school and she doesn’t believe some teachers and administrators are doing their best to help students like herself. Tuition for the media production program can range from $7,000 to $7,800 per year for domestic undergraduate students, according to the program’s website. This means MacKay, who suffers from an unpredictable and uncontrollable condition, is unable to fully participate like most of her peers who do not have any chronic conditions but is paying the same amount.

Students registered with Ryerson’s Academic Accommodation Support (AAS) “are provided with accommodation plans that are designed to meet their individual disability-related needs,” according to an emailed statement from the university. These plans include support and accommodations for students who cannot attend classes due to their disability and aims to give them access to what they missed from that class.

The AAS website lists multiple options, including access to peer note-taking, accommodated tests and audio recordings of lectures. However, professors can refuse the accommodations at their own judgement, creating another barrier for students. Additionally, peer note-taking is not offered for many courses as it solely depends on student volunteers, as previously reported by The Eyeopener.

In terms of mandating professors to record all lectures, AAS says this practice would represent a “universal design for learning” strategy that would likely benefit a wide range of students, including those with chronic diseases. However, they did not comment on whether this mandate would be implemented in the near future.

MacKay was first diagnosed with IBS at 10 years old and then started experiencing symptoms of endometriosis when she was 12 years old. MacKay was also diagnosed with anxiety, depression, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) before finally being diagnosed with fibromyalgia this year. Growing up, she accepted that her stomach would always hurt, but throughout her life she experienced difficulty receiving an accurate diagnosis because of her chronic condition and mental health challenges working in tandem.

“It’s well-known that people with chronic illness have a higher chance of developing mental illness because it’s such a struggle to live with a chronic illness,” says Dr. Lu.

She explains that a chronic disease diagnosis creates a biographical disruption, which is when a person’s vision of what their life will be changes. “You have an idea of how your life is going to go and then this bomb falls into your life,” she says. Although a person’s life settles eventually, the confusion and lack of control can cause a lot of mental distress and trauma, she adds.

In her first semester of university, MacKay felt pain in her back and hip. Chalking it up to a running injury, she first tried to rest, but then the pain spread to her other side and all the way up to her spine.

MacKay went to MedCan, a private health care clinic in Toronto, to see if they could diagnose her. She remembers spending a lot of her own money because she desperately wanted to understand the cause of her pain, just for them to eventually tell her there was nothing wrong.

“I kept being told that there was nothing wrong with me for the next four years,” says MacKay. She recalls doctors reading through her medical history, noticing her diagnosed mental health disorders and immediately dismissing her pain. “They would be like ‘It’s in your head.’”

But for MacKay, the symptoms are very real. “It feels like I ran a marathon and can’t move any muscles,” she describes. She’s always exhausted and has constant stomach pain, especially after eating. She also now has severe pelvic pain, is often nauseous and experiences frequent infections because of her weakened immune system from her fibromyalgia flare-ups, which increase her fatigue.

“And everyone’s expecting…for you to just be normal because you look normal,” MacKay says.

ast year, McCracken took a week and a half off school because her chronic pain became too all-consuming for her to function. She was in and out of the hospital three times in one week, and her time at home was spent lying on the floor of her bathroom trying to find some relief.

“I felt so awful messaging professors and being like ‘I can’t move, so I can’t be in class,’” McCracken says. She was struggling with her condition every day, while simultaneously having to attend class and complete her schoolwork, all while maintaining her grades and sustaining her social life. “It was just too much.”

MacKay says most people don’t understand that individuals with chronic disease have to work harder than those without any chronic conditions. She remembers being in a group project where her groupmate kept telling her she had been ‘zero help,’ repeatedly belittling and insulting her. But she stresses that students should be grateful for their own health instead of being angry at sick students who are struggling.

MacKay adds that the best solution is to create more awareness of the reality of living with a chronic condition. “I think there needs to be a lot more awareness, especially when you look at what’s being funded for fibromyalgia and endometriosis, which are often women’s issues,” she says. “They’re severely underfunded, under-researched and not well-understood, so that translates to the public not really understanding.”

Instead of making students with chronic diseases feel like something is wrong with them, she believes students without chronic conditions should pause and reflect on how lucky they are that they aren’t suffering. “I think people need to be a little more empathetic,” she says.

Leave a Reply