By Rowan Flood

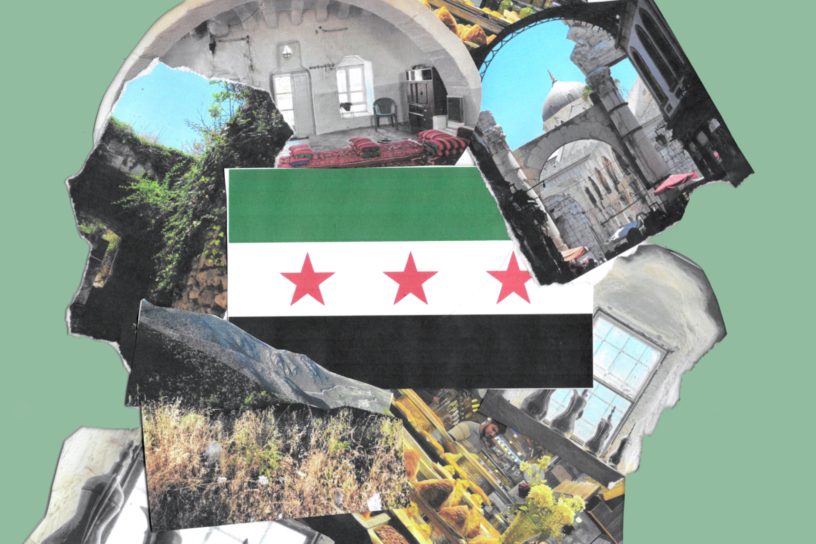

A mountain with sweeping views of the city below. A swing made with rope surrounded by olive trees. Narrow streets filled with markets in the old city of Damascus. The smell of white jasmine flowers in the air. These are some things Syrian students at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) are looking forward to experiencing again now that life in Syria drastically shifted a few months ago.

It was the middle of TMU’s exam season during the fall 2024 semester when Hamed Bakkar, a third-year computer science student, was preparing to return home to Syria for winter break when “everything changed.” He didn’t end up making the trip home but the reason for its cancellation was welcomed.

On Dec. 8, 2024, Syria experienced a historic transformation: then-President Bashar al-Assad was removed from office. The former ruler’s family had been in power for over five decades and many Syrian people suffered under his rule—from unjust imprisonments, intense mass surveillance, torture and more. The regime’s fall was swift and brought hope and relief to many.

Bakkar was born in Damascus and lived there for 20 years before coming to Canada as an international student. He said he’s supposed to graduate next year, laughing as he explained how difficult his degree is. “Do not go into computer science,” he jokingly warned with a smile.

He visited his hometown last summer and witnessed people still struggling under the al-Assad regime. On top of financial struggles and safety concerns, he explained there is often little electricity and poor internet.

Bakkar’s grandmother and mother still live in Syria and he continues to stay in touch with them while he’s away. As the regime was being toppled by the armed opposition group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), Bakkar had to balance the stress of exam season alongside exhaustive anxiety for his family’s safety.

“I didn’t study anything,” he remembered, not seeming too bothered as a laugh lit up his face.

He described the regime falling as “what we’ve been dreaming of our whole life.” His family tells him that many aspects of life are different and better now. He said although electricity is inconsistent, “basic human needs are there now.”

The new possibilities and opportunities

When Bakkar first came to Canada in August 2023, he planned to build a whole new life as, at the time, a promising future in Syria didn’t seem likely. However, his vision for the future has since “turned 180 degrees.”

While Bakkar feels unsure of what to do now, he can’t stop thinking of newfound possibilities he recently couldn’t consider. He explained that only a few years ago in Syria, he and his friends were planning to graduate and immediately leave the country. Now, his focus is graduating in Canada and then figuring out his life from there—but he’s certain Syria is going to be part of it.

“The biggest keyword is hope, right now in Syrians there’s so much hope”

Bakkar believes now is the time for people like him to “step up” and that young people can help build the country for the better. He hopes to return and that many new jobs will open, sanctions will be lifted and the economy will improve.

“We have so much to work with,” he said, speaking quickly as he imagined what could come next for his country. “We can start multiple businesses, multiple websites”—things that would have been difficult under the regime.

Marie-Joëlle Zahar, a professor of political science at the Université de Montréal, has also worked with the United Nations (UN) as a senior mediation adviser on the UN Standby Team and has been involved with its Syrian file since 2013. She agrees that if economic recovery picks up and gets the support it needs, there will be many more opportunities for young people in the workforce.

“Syria is going to need everything,” said Zahar, “It’s going to need bankers, engineers, doctors, professors, plumbers, electricians.”

While establishing careers and being part of the generation that grows in Syria is one opportunity, Bakkar and other students also plan on enjoying the country’s landscape, cities and culture.

Bakkar plans to return this summer. His eyes drifted up in thought and a toothy smile spread across his face as he described what he was excited for. First, not being terrified of crossing the border and being accused of saying something he wasn’t supposed to, then returning to childhood spots that have been closed off for years as military zones by the al-Assad regime.

One particular spot is Mount Qasioun in Damascus.

“It overlooks the whole city,” he said, his hand spread across the screen to describe the view. “It’s really beautiful.”

He also plans to go to one of his favourite places—the Old City of Damascus.

“It’s mind-blowing how beautiful it is,” he said and explained how its narrow streets—thousands of years old—are filled with markets and Islamic architecture.

Besides seeing his hometown, Bakkar wants to travel the country. He now feels a new sense of security, and with it, the freedom to immerse himself deeper in a place he loves.

The hope spreading through families

Judy Alzain, a third-year industrial engineering student, also pictures herself and her family enjoying newfound freedom. Alzain feels able to enjoy the country she loves but also to see her parents—who were born in Syria—happy and safe. When things stabilize a bit more, she wants to visit with her mother, an idea they had concluded as unrealistic before.

“There’s a real hope,” said Alzain, referring to the possibility of seeing family—aunts, an uncle and cousins—for the first time in nine years.

Alongside reuniting with her family, she is hopeful to return to Boudan, a village not far from Damascus where her parents and grandparents were born.

Alzain is eager to see jasmine flowers, Syria’s national flower, which she said are everywhere. The small white-petaled flowers bring back distinct memories for her.

“I would be walking down the neighbourhood with my mom and could smell the jasmine off the streets. It’s so beautiful. I would pick one and put it in my hair or take it [home] with me,” said Alzain, pinching her fingers together.

As she and her family watched the news and got updates from family back in Syria, they could hardly believe that the regime was falling. “It was so surreal,” said Alzain, “We were excited.”

“Syria is going to need everything…it’s going to need bankers, engineers, doctors, professors, plumbers, electricians.”

While this excitement didn’t come without some concern, worries continue to decline as her family in Syria gives promising updates. They tell her people are celebrating in the streets and that they feel hopeful.

“The biggest keyword is hope, right now in Syrians there’s so much hope,” said Alzain as she described people talking about opening businesses and rebuilding their homes. Her father, who currently lives in Saudi Arabia, is considering opening a pharmacy and retiring in Syria. He supports whatever Alzain wants to do with her future, but for him, being in Syria with family is his main goal.

She recalled once telling her father, “There’s no future for me in Syria.” That no longer has to be the case now. Alzain envisions spending summers in Damascus—a place that holds “my culture, everything I know, our home recipes, the stories my grandparents would tell me, my hometown.”

The complexities that come with the change

Despite many people with connections to Syria feeling encouraged by the developments, returning to the country—whether visiting or residing—is not straightforward. Since 2011, the al-Assad regime—also backed by Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah—has orchestrated a devastating humanitarian crisis against those who oppose it through systematic murders, displacements and more as explained by Al Jazeera. Much infrastructure has been destroyed and there is a lack of public services as published by CBC. Economic recovery is needed but complicated.

Zahar explained that challenges for recovery arise from international sanctions and the fact that HTS—the group that led the overthrow of the regime and may eventually control the government—is considered a terrorist organization by many countries according to the UN Security Council.

The word “stabilize” is used by some students to express what needs to happen before they return. There remains uncertainty among many surrounding what comes next.

Zahar, whose career expertise lies in conflict resolution, peace operations and post-conflict processes, explained that for Syria to move forward peacefully and successfully, ensuring security, effective control and economic revival of the territory is critical as she said Syria has lost “50 years of development” under al-Assad’s brutal regime.

While leaders of HTS have made themselves available to govern, constitutional reform and elections will take time with HTS’ leader specifying four years.

However, years of transitioning may be positive because generally “transitions that the international community designs for peacebuilding tend to be hurried,” and building a solid foundation is necessary for stability. Zahar said that rebuilding trust within the nation is important for peaceful elections and constitutions need time for consultation and negotiation.

“What I wanted to do ever since I stepped out of Syria is to talk about it”

While building stability within the country is one complex aspect that must now be considered, there are also complications for Syrian refugees and permanent residents in Canada. Sofia Ijaz, a refugee and immigration lawyer in Toronto, has Syrian clients who were quick to ask her, “I have a refugee claim pending, what now?” following the regime’s collapse.

Her answer to the “what now” question isn’t so simple, saying that she’s seen various postponements of refugee hearings for Syrians. She said while it’s not clear if it’s related to recent events, it’s “certainly noticeable after the fall of the Assad regime.”

Ijaz wants her clients to receive a fair individualized assessment of risk and not have decision-makers such as the members of the Immigration and Refugee Board wrongfully assume that the regime being gone means safety for all.

Getting a refugee claim accepted and becoming a protected person in Canada is one step to remaining in Canada but it doesn’t provide complete assurance as returning to Syria, even briefly, can put their status at risk, Ijaz explained.

She said going temporarily to Syria as an accepted refugee in Canada can potentially lead to cessation—the removal of refugee status. If they’re a permanent resident who got the status through an accepted refugee claim, their status can be at risk due to their visit, Ijaz explains. Even renewing one’s passport could end up “triggering cessation proceedings,” she added, saying it’s decided case-by-case.

“It’s incredibly painful because there are people who have not seen their loved ones for decade or more. There are people who still don’t know the whereabouts of disappeared family members,” she said.

Ijaz believes Canada has a responsibility to ensure that if someone does want to return, it’s an informed and voluntary decision and “visits to Syria in this context should not trigger cessation proceedings.”

Finding a place and way forward amidst tremendous transition

Sham Al Mukdad is a fourth-year language and intercultural relations student at TMU who spent most of her childhood in Syria and has a deep love for the country, saying, “Its people are beautiful, warm-hearted, they are the kindest humans ever.”

She was around 11 years old when she left Syria and hasn’t been back since, partly because she did not want to return to a country under the rule of al-Assad.

Al Mukdad has also spent years advocating for Syria and its people.

“I always had this responsibility to talk to the world and Canadians about what was happening,” said Al Mukdad, who explained that she always carries a deep awareness about the “wrongfully detained in underground dungeons” controlled by the al-Assad regime as well his militias. “What I wanted to do ever since I stepped out of Syria is to talk about it.”

She explained that ever since she left the country and could speak more freely, speaking about the country’s repressive measures, detainees and widespread poverty was something she felt compelled to do.

When she first arrived in Canada, everything was so new and different—all she could do was take it one step at a time. Despite the challenges of adjusting to a new country, Al Mukdad’s high-achieving personality pushed through—she did well in school and was her high school valedictorian with her speech being published in Maclean’s.

Al Mukdad considered going back to Syria to be a teacher and a part of her does feel called to return and help build the country up. Yet, her fierce determination to help fix wrongdoings and support Syrians was somewhat changed when a professor who recognized her resoluteness gave her some words of wisdom. “Sham, you cannot fix the world alone,” they told her.

She’s never forgotten those words. She hasn’t stopped wanting to help Syrians but has since changed her perspective of how she can. She’s now thinking of returning to volunteer, teach or build, for months at a time when the country’s social and political climate stabilizes a bit more. She wants to be a part of how the country grows and recognizes this effort must be done with the help of others.

Al Mukdad does want to become a professor, but for now, she’s still deciding what her next steps will be—expressing an interest in immigration law. One thing she knows for certain is that advocating for Syria will continue to be a part of her life, and she’s recently decided she will go back—letting go of her original uncertainty—after an intimate memory resurfaced.

“It was a little swing that was put up on an olive tree,” said Al Mukdad, describing how she built it with old rope. She would often go to the tree after school and spend hours talking with it. Her olive tree was surrounded by many others and the view “was the most beautiful, majestic scenery.”

She knows she has a place to return to.

Leave a Reply