By Rogene Teodoro

To integrate the profound generational relationships between textile design and lived spaces, TMU-graduate students are exhibiting works both public and personal. From Feb. 28 to March 22, Artspace TMU invites viewers to uncover political dimensions through textiles.

With various narratives presented through interpersonal designs, each artist points to a new story. Curated by TMU Assistant Professor, Almudena Escobar López, Woven Together Fabrics of Belonging presents a feminist and social justice approach to themes of family and community.

Their opening reception took place on March 6 from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. to highlight the work of TMU students pursuing graduate studies, Mina Keykhaei, Azadeh Monzavi and Muna Nzeribe. Through various works, each artist communicates a sense of belonging to those who visit the exhibition.

“All of the works were created before the exhibition came together and so the gallery extends its reach to empower the artists to keep creating work,” said exhibit coordinator Jamie Edghill.

Feminist art history became a movement during the 1970s when art enthusiasts began to question the lack of women artists in their communities. Women were faced with the truth that they were not treated as equals to their male counterparts. Even today, female-credited art remains a male-dominated field, resulting in womens’ contributions being undervalued.

Womens’ connection to textiles and textile art goes far back in history, engaging in tasks such as sewing and embroidery. This led to the creation of artifacts like the quilts featured in Threads of History: Repatriating Canadian World War II Quilts, which were made using upcycled fabric from the creators’ environments.

As one of the three artists, Nzeribe focused on her parents’ wedding as her piece’s focal point. In her art piece, titled Oguta-Lagos-Toronto, footage from the ceremony is projected over a layer of dark blue African wax print fabric with a striking bright orange pattern. Positioned in front of the wall is a table with two plastic chairs. The table is adorned with a white table cloth, plates, cutlery and a vase of flowers to add to the wedding theme.

The fabric’s pattern resembles the material used in garments worn by members of prominent Catholic groups in Nigeria, such as the Catholic Mens’ Organization and the Catholic Womens’ Organization. The history of the African wax print fabric used, also called ankara, extends back to the 1850’s when the Dutch colonized Indonesia.

“In Nigeria and in many Christian households, it’s customary to have a Catholic wedding and then a traditional wedding,” Nzeribe explained. “I thought it was absurd that this westernized concept of religion has to be held to the same standard, but even sometimes higher than traditional religious rituals and practices.”

She added, “I thought that it was interesting to use that fabric as a representation, the physical manifestation of globalization and colonization.”

Like Nzeribe, Monzavi expressed a passion for conveying messages through her textile art. Her artist statement reads that she uses textile crafting as a form of communication to address sensitive themes like home, identity and trauma experienced by BIPOC communities and individuals. She uses techniques such as crocheting, knitting and sewing to create her new media artwork.

Monzavi learned crochet as a child. While living as a refugee from Türkiye, a group of female neighbours taught her how the artform since it was a popular way to pass the time.

Monzavi said, “I lost my mom when I was eight, so while I lived in Türkiye, I didn’t have a female figure in my life. And so I hadn’t done [crochet] for 20 years until I picked it up again during the [COVID-19] pandemic from my work.”

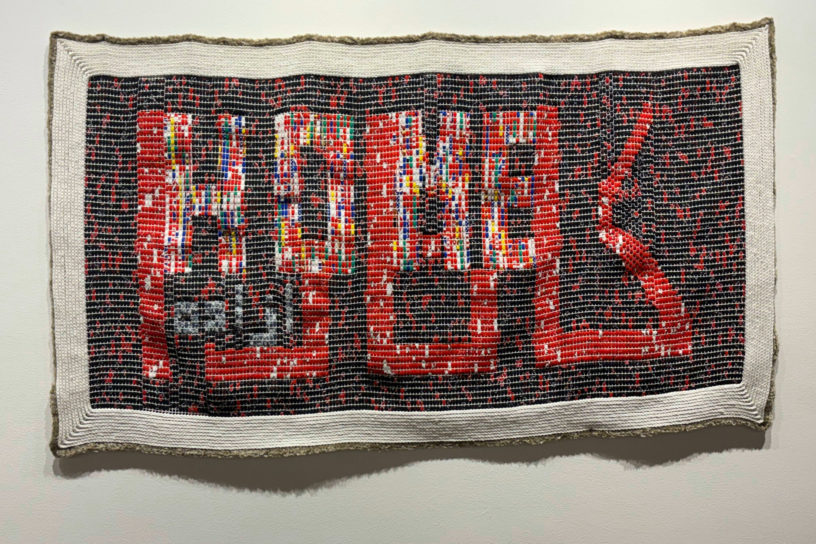

Anonymous Was a Woman, one of Monzavi’s crocheted pieces, resembles a label used by galleries to give information about artwork—its background was made with white “Eyelash Yarn” and black “Squeaky Clean Yarn” rectangles to represent text. The piece was made to acknowledge the women artists whose work and identities have been discredited throughout history.

“Historically, textile works and women’s work has been undermined—especially textile works in the sense that they happen to be done a lot more by women,” said Monzavi.

Her inspiration for this piece came when she saw numerous artworks displayed in galleries that were labelled “maker unknown,” “maker once known” and “made by a French/British/Indigenous woman.”

Edghill said, “For me, it gives me an immense feeling of warmth…It makes me feel nostalgic. It reminds me of family. It reminds me of a found family because of the use of upcycled fabrics. The narrative element really draws me in,” when talking about the exhibit.

The exhibition will run until March 22 at Artspace TMU.

Leave a Reply