By Shaheen Ramputh

Stanley Doyle-Wood’s quest began when his three-year-old daughter came home from daycare upset because her classmates told her the swings were only for white kids.

He then realized the need to make daycare centres in Toronto more sensitive towards visible minorities. In order to do this, Doyle-Wood, a Ryerson early childhood education student, and other concerned parents and teachers at Davisville Child Care Centre begun an anti-racist committee. At the centre of the group’s andate is addition of culturally diverse books to the centre’s library.

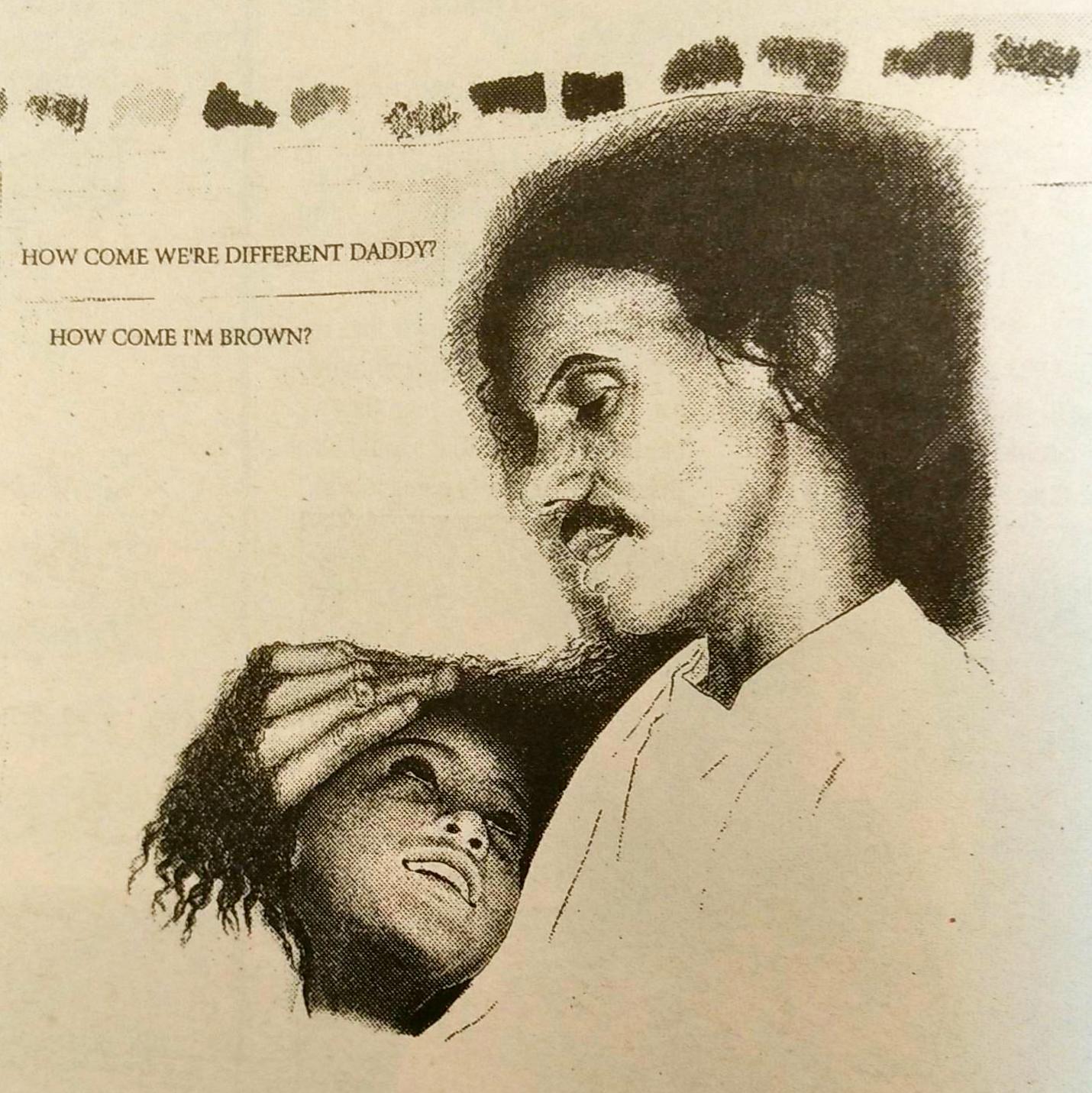

But unlike other parents, Doyle-Wood took his dedication a step further. Doyle-Wood is currently in the process of publishing his first children’s book, entitled, Chisani. The book, names after his daughter who is now seven, is about a child who wants to know why the colour of her skin is brown. Chisani will be distributed throughout North America by Scholastic Books Inc. this fall.

It was the treatment his daughter received at the centre and the books he noticed his children were bringing home that propelled Doyle-Wood to write Chiasani. “I decided to get involved with the daycare by reading to the group once a week, but I didn’t think it was enough,” says Doyle-Wood, who has a four-year-old son now attending the daycare.

“[The books] were generally for white people,” he recalls. “My children are a combination of many cultures but they were not seeing kids like them in any of the books they were reading. They couldn’t understand why nobody looked like them.”

Doyle-Wood knows what it’s like it’s like to be treated as strange. The racial intolerance he experiences while growing up made him sensitive about his own skin complexion. His mother was part Irish and Portuguese and lived in England while his father, mixed with African and Carib Indian returned to his home in Trinidad before he was born.

Growing up in Blackpool, England, was extremely difficult for the young Doyle-Wood. He was often the butt of many jokes because he did not look like his other with his tan complexion and slightly kinky black hair.

“I was called everything but normal — paki, nigger, coon — I became ashamed of who I was and that my blood was tainted by those of people with colour,” said Doyle-Wood.

The inability to find secure employment forced the young mother and her three-year-old son onto the streets. Doyle-Wood grew up in various “Home for Unmarried Mothers,” and enjoyed the luxury of a bed and breakfast when they did have money.

“Mom and I lived like gypsies but when times got really tough, three social workers hauled me off to the Bernardo Home. It’s kind of like the Covenant House, but there are a string of them across the United Kingdom for us troubled, poort kids.”

Doyle-Wood spent a year at the home and at seven his mother had saved enough money to settle in a low-income housing project, “where even the police would refuse to go,” recalls Doyle-Wood.

Still, he stayed in school and eventually went to the University of Wales. However, after a year at university, Doyle-Wood was not content. He felt empty and knew he was in search of something, though he did not know what.

“I had this identity clash, I was trying to find myself but did not know it,” said Doyle-Wood. His search for identity led him to travel and work across Europe and Asia and eventually, in 1979, to Trinidad in search of his father, a man he had never known. As he became an adult he learned of the circumstances leading to his father’s absence and with this knowledge was able to put his anger aside. When he finally met his father he was overcome with joy.

“I immediately changed the minute I met my dad. I no longer wanted to be white. I wanted to embrace my father and his ancestry,” says Doyle-Wood. “I had finally accepted who I was.”

Today, through his writing, Doyle-Wood is in the process of both embracing his family and fulfilling his commitment to the younger generation. Chisani, which is no more than 10 pages, has bright and colourful drawings of the family members in both Doyle-Wood’s and his wife’s family lineage. Doyle-Wood spent hours painting the faces of family members from old photographs, taking him almost eight months to complete.

“The story is my life,” Doyle-Wood says. “It was both my way and my children’s way of linking themselves to their ancestry. I want my children and hopefully others who read it, to gain confidence in their place in this world and realize that they are indispensable.”

Doyle-Wood is already working on the second book in a series he calls “a spiritual journey.” “I want these books to teach kids to look within to find happiness, and love who they are and where they came from.”

A faculty member in the early childhood and education program at Ryerson became aware of his work and nominated him for the Excellence in Education award which he received last term. The Ryerson Award of Merit is an academic award given to Ryerson students who have made a significant contribution to the community.

“He is an exceptional student. His strong sense of ethics combined with his creativity makes him stand out among his classmates,” says June Pollard, the director of the early childhood education program.

Pollard, who taught Doyle-Wood in his first-year, believes he was an asset to his classmates. “He was always bringing up issues in class. He definitely raised our awareness of the lack of sensitivity towards visible minorities in the day care centres,” says Pollard.

But Doyle-Wood does not want to stop with simply raising awareness. He wants to continue with his education and even perhaps receive a doctorate for his studies in racism in children’s literature.

His ultimate goal is to open his own daycare centre where a heavy emphasis will be placed on oral and visual learning and racial tolerance.

Leave a Reply