By Elaine O’Connor

It could be the most religiously diverse street corner in the city. Walking along Bloor Street West just east of Spadina Avenue, religious signage takes over the urban adspace. Message boards bearing a queer-positive triangle announce a prayer service, street signs point to a Buddhist temple, and Korean-language characters call pedestrians to step into church. It’s not typical downtown billboard fare. That’s because four wildly divergent religions — the Toronto Baha’i Centre, Bloor Street United Church, Tengye Ling Tibetan Buddhist Centre and Toronto Korean United Church — share a city block near Bloor and Huron Streets, turning this corner of Toronto into a religious pedestrian mall.

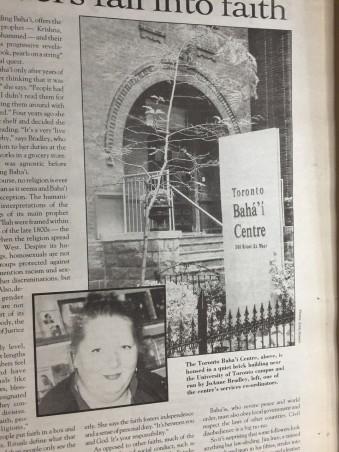

But many stroll right by the Toronto Baha’i Centre at 288 Bloor St. W. without even knowing it’s a place of worship. Not only does the large brick building offer liffle in the way of window dressing — only a few posters deck its glass display case — but, more likely, passersby haven’t a clue what’s being offered inside.

It’s an awareness issue that Toronto Baha’i Centre services co-ordinator JoAnne Bradley says she faces daily. “Most people have just never heard the word Baha’i before,” says Bradley, who decided to follow the Baha’i faith four year ago. “I just say it’s one of the major world religions and leave it at that.”

In fact, it’s a religion followed by an estimated five million people from over 235 countries and 2,100 racial, ethnic and tribal groups. Many think it’s a Jewish or Christian sect, but it grew from the teachings of the Islamic prophet Bab and was established in 1844. One follower, known as Baha’u’llah, became its central prophet and the scriptures he wrote, during a lifetime of persecution and imprisonment in Iran, form the basis of the faith today.

Baha’is believe in the unity of the world religions, seeing all as stemming from the same spiritual source. They hold world peace as their ultimate goal and promote ideals like sexual and racial equality, universal education, world government and elimination of prejudice and poverty.

The religion came to North America in 1893 but is most popular in India, where roughly 2.5 million people call themselves Baha’is. There are over 140,000 adherents in the United States and the 1991 census found 14,730 followers in Canada. However, there aren’t any to be found at Ryerson, at least not in an organized group. RyeSAC campus groups administrator Leatrice Spevack says Ryerson hasn’t had a Baha’i since the Multi-Faith Centre was introduced in 1998 and the group has encompassed into the centre.

The Toronto Baha’i Centre, near the University of Toronto, is home to several Toronto-area students looking to worship, although the centre feels little like a church. The mahogany paneling, burnished wood staircase, stained glass windows and chandeliers suggest a previous incarnation as a faculty house. Despite the unorthodox surroundings, the religious message is clear. A large blue and the religious message is clear. A large blue and red banner reading “One Planet, One People… Please” hangs high on one wall.

Bradyley, an auburn-haired woman with a round face, sits in the bookstore and explains the faith with a patience and skill that comes with practice. She explains Baha’i sees all religions as attributes of God, and no religion, including Baha’i, offers the definitive path. Each prophet — Kishna, Buddha, Jesus and Mohammed — and their teachings are seen as progressive revelations, “chapters in a book, pearls on a string,” in humanity’s spiritual quest.

Bradley came to Baha’i only after years of avoidance. “I just kept thinking that it was just another religion,” she says. “People had given me books, but I didn’t read them for years. I just kept carting them around with me every time I move.” Four years ago she pulled a book off the shelf and decided she liked what she was reading. “It’s a very ‘live and let live’ philosophy,” says Bradley, who in addition to her duties at the centre works in a grocery story. Bradley was agnostic before becoming Baha’i.

Of course, no religion is ever as utopian as it seems and Baha’i is no exception. The humanitarian interpretations of the writings of its main prophet Baha’u’llah were framed within the era of the late 1800s — the time when the religion spread to the West. Despite its humanitarian leanings, homosexuals are not on their list of groups protected against prejudices. They mention racism and sexism along with other discriminations, but bot homophobia. Also, despite claims of gender equality, women are not allowed to be part of its highest religious body, the Universal House of Justice in Haifa, Israel.

But on a daily level, Baha’is go to great lengths to make all members feel comfortable, and have eliminated rituals like prayer ceremonies, blessing rituals or designated hymns which they consider potentially divisive.

“God sends faith, people make religions,” Bradley says. “People put faith in a box and decorate the box. Rituals define what the box looks like when people only see the box.”

Baha’i meetings are simple for this reason. There are no priests, no clergy.

Devotional meetings of 20 to 30 members are held Monday evenings. People gather to hear passages on a given topic taken from many holy writings — the teachings of Baha’u’llah, the Bible, the Koran. Members each take turns preparing the readings and afterwards there’s time for individual prayer. “I call it a meditative experience,” says Bradley.

Others wander into the bookstore and scan the shelves. Among titles like The Book of Certitude, The Hidden Words and The Seven Valleys, are religious children’s books, compact discs and greeting cards. A dark-haired woman in tortoise-shell glasses browses the shelves while Bradley talks, crouching to see the books on the bottom.

She is Nassim Rouhani, a calm, soft-spoken University of Toronto student, who has followed Baha’i all her life. She was born into the faith and watched how her Persian parents acted on their beliefs by volunteering on development projects in their former home in the Philippines.

“I was really lucky,” she says, explaining her parents never forced her to follow them. For her, becoming Baha’i was “a choice, a conscious choice.”

The nutritional science student follows their example and volunteers with the elderly. She says the fair fosters independence and a sense of personal duty. “It’s between you and God. It’s your responsibility.”

As opposed to other faiths, much of the Baha’i lifestyle and social conduct, such as sexual activity, is left to an individual’s judgement. There are no dietary requirements, dress codes or prohibitions against interracial or interfaith marriages, abortions or Western medicine. Followers are expected to meditate and pray twice daily, observe nine holy days and fast for 19 days once a year. They are encouraged to do community service and should swear off alcohol, illicit drugs, swearing, gossip, adultery and all other venial sins. But transgressions are strictly between Baha’i and God — no fire and brimstone here.

In fact, there are no all-powerful leaders to preach damnation even if punishments were in order. The Baha’i faith is almost secular in its organization, a religion for the non-religious. Each local group democratically elects a spiritual council of nine members, who serve mainly as guidance councillors. They can’t even run for a position on the council — there are no nominations and voting by all group members is secret.

“As individuals they have no rights above and beyond all others,” says Bradley.

Baha’is, who revere peace and world order, must also obey local government and respect the laws of other countries. Civil disobedience is a big no-no.

So it’s surprising that some followers look anything but law-abiding. Jim Ince, a tanned and weathered man in his fifties, strides into the bookstore wearing sunglasses and a leather bomber jacket. Hardly conventional church gear, but it doesn’t matter here. The self-described rebel might not look like a religious man, but Ince has been a devout Baha’i for 27 years.

He came to the faith by accident. As a wild young man in his twenties, he picked up a hitchhiker on his motorcycle and drove her to a Baha’i house in Aurora — the only place her mother had said she could stay if she didn’t want her to call the police. (A smart move since Baha’is are forbidden to drink, use drugs or be promiscuous).

“I took her there and then promptly forgot about her,” Ince remembers. He may have forgotten the girl, but he liked the friendly atmosphere at the Baha’i house so much he came back, each time impressed by the broad mix of people. He originally decided not to become Baha’i then but later changed his mind.

“You can be a Baha’i and not know it,” he laughs. “You don’t find the Baha’i faith, the Baha’i faith finds you. It’s a gift, but you don’t have to accept it.”

babibuba

Nonsense.