By Lysanne M. Louter

Here, in this commercial studio with fluorescent tube lighting and white brick walls, the scent of musky sweat hangs in the air. This is where ninjas are made.

Every day, black-clad warriors trains for two, sometimes three hours, tumbling and rolling on the chalky red and green mats that cover the floor. The hushed voices of the students mingle with the muffled sound of traffic coming through the third floor windows. Although the ceiling is laced with beams and pipes, the space is surprisingly comfortable, almost spiritual.

That sense of spirit and history in the studio transcends the bad reputation martial arts have gained. Misconceptions about violent and bloody video games such as Mortal Kombat and Street Fighter have led many people who play these games to become interested in martial arts. But all sorts of martial arts are easily confused by society, and misconceptions lead to a blurring of an ancient art form with supposed modern-day assassins.

In actual fact, ninjutsu, or the art of the ninja, is largely based on meditation, spiritualty, self-controlled and physical conditioning. Essentially, ninjas hope to attain enlightenment, or the development of jihi no kokoro, which means a benevolent heart.

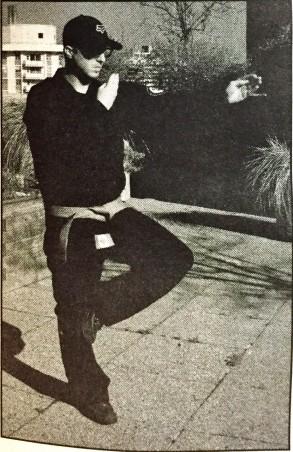

Robert Chatterton, a 23-year-old who works in sales, bows respectfully before stepping onto the mats. He has been taking ninjutsu classes at the Kageyama Dojo (meaning school) at Yonge and Wellesley Streets for over a year. He says that his interest in martial arts was primarily spawned from watching martial arts movies.

Chatterton, like other young boys, grew up watching Steven Segal, Jackie Chan and Bruce Lee. Although he stopped taking kung fu lessons in high school, he never lost his interest in martial arts. Last year, after attending kickboxing, tae kwon do, and karate classes, he sat in on a ninjutsu class. He was surprised to find how well it suited him.

“It made the most sense,” Chatterton says, comparing ninjutsu to the other martial arts he had tried.

“It wasn’t really competitive. It was go-at-your-own-pace but you also learned everything you would need to know to defend yourself,” he says.

“And yet, there was a spiritual aspect and to be honest, a brutal aspect, too.”

The tradition of ninjutsu is 900 years old and the core of its values remain true to its beginning. Students of ninjutsu practice visualization and breathing exercises while training their whole bodes. Junan taiso, or body conditioning, is attained through breathing, stretching, strengthening and aerobic exercises. Historically, ninjas are known as the invisible warrior; this training allows the ninja to move stealthily and be responsibe to their surroundings.

Chatterton follows a program that includes several training methods. The Kageyama’s students learn how to protect themselves through striking, kicking and blocking methods, as well as using grappling, chokes and escapes, rolling, leaping, tumbling and silent movement.

In an office, with an octagon-shaped window looking onto the adjacent training space, the Kageyama’s owner sits behind his black metal desk. The shidoshi, or teacher, Greg Tremblay leans back in his chair and braces his hands behind his head. Behind him is a large photograph of a black-clad ninja standing regally against a fall forest landscape.

“That’s me,” he says, smiling up at the younger version of himself. “It was taken sometime in the early eighties.”

Tremblay began his martial arts training as a young man in 1972. While at a knife fighting seminar in 1982, he was introduced to ninjutsu. He travelled to Ohio regularly to train under Shidoshi Hayes who was the first American awarded that title. In 1986, Tremblay received the rank of shodan or first degree of black belt. Later that year he received the title nidan or second degree black belt.

In 1994, he was asked to teach ninjutsu to children at a friend’s dojo. In 1996, he opened his own school, the Kageyama Dojo. In 1997, Tremblay received the title of yondan, the fourth degree of black belt.

In 1998, he took the test for the next level of black belt, godan. This test determines a ninja’s level of awareness. The candidate sits in a traditional kneeling position called seiza with his eyes closed. The grandmaster stands behind him with a sheinai, a stick wrapped in leather, with his eyes closed. At some undetermined point, he strikes at the person kneeling on the floor. If the person avoids the blow, they pass the test. Tremblay passed on his second attempt in 1999. He was also awarded the title of shidoshi.

In September of last year, he went to Japan for three weeks to train under grandmaster Dr. Masaaki Hatsumi and meet other ninjutsu students.

At the Kageyama Dojo, Tremblay trains students who are police officers, bodyguards, and military personnel. Training in the use of all sorts of weapons serves to prepare them for the many types of situations they might face.

The weapons of ninjutsu are divided into five categories: sticks, blades, flexible weapons, such as chains and ropes, projectile weapons, and combinations of weapons such as spears. “Any weapon that exists now fits into those categories,” Tremblay says. “Even an atomic bomb is a projectile.”

Chatterton realizes that his motivations for learning ninjutsu were founded on stereotypes created by martial arts movies but he values the lessons he has learned. “It’s a really interesting art form,” he says. “And it’s unfortunate that most people don’t know about the other aspects of it, other than what movies portray.”

Tremblay has decided to let things be. “Most views that people have [of ninjutsu] are stereotypical, cinematic renditions,” he says. “One way to deal with it is to just ignore it. It’s for entertainment and as long as people understand that then they can get past it and do some serious training.”

Dr. Hatsumi, the current grandmaster of ninjutsu, addresses the growing popularity of the ninja in his book Ninjutsu: History and Tradition. “I must say that there is really nothing wrong with the entertainment industry bending the lore of the ninja to fit the demands of the public,” he writes.

“However, it is a little surprising that Japanese and American audiences would believe that the weakly-researched flights of fancy of fiction writers were the true essence of ninjutsu.”

There are hundreds of web sites, claiming to be the foremost source of information on Japanese martial arts. But, unless they are run by a dojo, they may be inaccurate and downright harmful. Because they present information and techniques incorrectly, they could potentially instruct people to seriously injure themselves or someone else.

“There is so much junk on the Internet and everybody has access to it,” Tremblay says. “As humans we think that if it’s written somewhere, it must be real. In truth, if it’s being generated through playing Street Fighter video games, then I would say that it’s kind of dangerous.

Back in the studio, Chatterton joins his partner in the centre of the mats. They begin a slow-motion act of strike then block, strike then block, only pausing occasionally to give each other advice. It is a fluid dance of motions as they take turns attacking and evading.

At the end of the class, Chatterton slings his backpack over his should and throws his blue sports cap over his damp bleached-blonde hair. As he trots down the three flights of dimly lit stairs to the alleyway below, something suddenly becomes apparent. Although he may not look any different than anyone else passing in the street, he is different. He is a ninja.

Leave a Reply