What started as a simple request for a bigger room has turned into a two-year-long struggle for understanding

By Emily Bowers

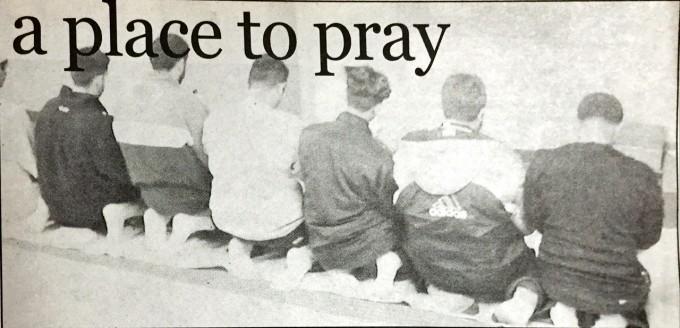

The light wind laps the Quad, lifting the sound of religious devotion from its grassy plain to the windows of the Kerr Hall classrooms nearby. The curious appear on the concrete steps or the brick walkway, pausing for a moment in their Friday afternoon to watch the group of Muslim students perform their prayer.

It’s a simple motion, the fluid repetition of standing up and kneeling back down, one repeated by millions of followers of Islam around the world. But the stifling lack of space for students to join together on campus and perform that simple motion has caused a deep rift between students and administration. Many now question whether the university’s policy of being a secular institution is hampering the religious freedom of its Muslim students.

With the Ryerson Muslim Students’ Association out of options to offer to the administration, and Ryerson not offering any solutions that Muslims say don’t go against their faith, the stalemate has become frustrating. The students are now considering taking a big step and filing a complaint to the Ontario Human Rights Commission, saying their religious rights are being violated.

Fouzan Khan, the 22-year-old RMSA president, is looking closely to make sure they’ve exhausted all the options on campus.

“It’s going to be a big deal,” he says. And it’s a step that’s getting closer, after the latest rejection. RMSA was told it could book a room in Oakham House for the prayer. But the largest room, Thomas Lounge, has a standing capacity of about 150 and Khan was told on Monday that it is booked most Fridays.

For now, the issue is stagnant and the students are left to pray in protest — taking over A60 in Jorgenson Hall or the Credit Union Lounge, one floor up. Or on days when the weather was nice, they prayed in the Quad. But even those lounges are cramped and snow is covering the Quad. Patience on all sides is wearing thin.

Khan, for his part, says he is looking forward to submitting his resignation at the end of the school year. His usually calm demeanour waivers as he talks about the mind0boggling frustration he has faced in his plight for prayer space.

“It has been crazy,” he says with a defeated smile that does not touch his deep brown eyes. “It’s a hard position to be in.”

On the other side of the brick wall, Linda Grayson, Ryerson’s v.p. administration and student affairs, is visibly frustrated with the constant questions.

On a Friday afternoon during a party in the Ram in the Rye, Grayson doesn’t want to talk about prayer space. She sips from her wine glass and casts her eyes to the side, impassively surveying the small crowd.

Beyond reiterating the university’s policy of being a secular institution, she doesn’t have much to say. She wants to leave it to the students to find a solution that works for everyone.

Expanding on that policy is tough for her — she blinks rapidly and stares blankly into the crowd. Her voice rises as she tries to define the university’s role in the religious life of its students.

“It’s about separating church and state,” she says forcefully, seemingly unwilling to accept that students religious lives can spill into their academic ones. However, in Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms, there is no mention of the American constitution of a legal separation of church and state.

She quibbles on the meaning of the word accommodate, standing by Ryerson’s definition that they are not actively hampering the Muslim students’ religious expression. Accommodation, she says, does not mean providing prayer space.

“We are a secular institution,” says Grayson. The university’s policy is to not inhibit religious freedom but also not to openly accommodate and promote any particular faith. She says that allowing religious exemptions for exams — an argument some say goes against the school’s secular policy — is not overstepping that line but in fact adhering to the university’s policy.

Grayson says that by providing the Multifaith centre in the basement of the business building, the school is backing up that policy. The space is open for use by an religious group but on a Friday afternoon, at least 150 Muslim students are packed into the room that holds about 50 people comfortably, their shoulders and knees squeezed together. Some line the hallway outside, trying to retain the vital connection to their group that adds strength to their prayers.

In Islam, one of the world’s largest religions, Salat-ul-Jum’a (prayer on Friday) is a key ritual of worship. Friday is the faith’s holy day, similar to Saturday for Jewish people and Sunday for Christians. The exact time of the prayer varies according to the position of the sun but generally falls between noon and early afternoon.

And while the students search for a permanent home on campus, the university’s administration will not let them book any facility on campus for the purpose of prayer.

Khan says he had no idea he would run into a brick wall when his group tried to find space to pray.

“It’s been frustrating,” Khan says with a sigh. The second-year ITM student was thrust into the role of president in January 2001, elected by the association’s executive after the last president, Kashif Shaikh resigned.

“He had failed to meet any of the objectives,” Khan says. And the pressure that Shaikh faced is now the driving force of Khan’s tenure as president. “(At meetings of RMSA) you can see it on their faces — ‘you’re not doing your job,’” he says.

RMSA says it could draw as many as 400 people for Friday prayer, if they had space. Since RMSA started asking for that extra space, most notably for use of Kerr Hall’s lower gym, Ryerson’s administration have repeatedly denied those requests. Apart from the Ryerson-as-a-secular-institute argument that the administration stands by, some say it’s got more to do with ignorance of Islam than any school policy.

And the province’s human rights code is explicit in its description of religious rights violation.

“It doesn’t matter whether or not discrimination is intentional: it is the effect of the behaviour that is important,” it states. “Where a rule conflicts with religious requirements, there is a duty to ensure that individuals are able to observe their religion, unless this would cause undue hardship because of cost, or health and safety reasons.”

Muslms do not need a space to pray that is used for only that purpose. For every prayer session, each Muslim will kneel on special mats that have been blessed. That’s the mats only — not the floor they rest on. Using the lower gym will not turn the facility into a mosque, say RMSA members.

A frustrated Khan says the solutions the administration proposed would not improve the situation.

In an e-mail to RMSA, Grayson offered three solutions the university deemed acceptable, including praying in smaller, separate groups, praying at different time of the day or using a neighbourhood mosque at 100 Bond St.

Islam dictates that prayer groups are stronger when more people are together, so breaking up into several groups contradicts the religion. So does staggering the prayer time — having small groups take turns praying in the Multifaith centre.

The third option, praying in the mosque at 100 Bond St., just a few steps off the Ryerson campus, is as problematic as cramming into the Multifaith centre.

Steve Rockwell, the owner of the building at 100 Bond St., which includes a clothing store, a restaurant and the mosque above, says his place is packed for Jum’a. It gets so crowded that Rockwell closes the clothing store for an hour and lays mats on the floor in there to accept the overflow.

Rockwell says that Marion Creery, Ryerson’s director of student services, asked if his mosque could be made available on Friday’s at 2:30 p.m. Rockwell agreed, but said that prayer time is long finished at that hour. Only in the midst of summer is there a small window of time when Jum’a is that late in the day, says Rockwell, who hosts a show on Vision television.

“I realized Ryerson administration wants to play me off the students,” Rockwell says as he chips away at the slush and ice lining the walk leading to his small mosque.

“A Muslim is set in his prayer times.”

This is not a new problem for Ryerson’s Muslims. In The Eyeopener’s Jan. 26, 2000 issue. Muslim students complained that the Multifaith centre was too small and they had made a request for the use of Kerr Hall’s lower gym, which was rejected.

RyeSAC took up the cause in early September 2001.

Alex Lisman, RyeSAC’s v.p. education said he began talking to RMSA after campus groups administrator Leatrice Spevack told him about the cramped conditions in the Multifaith centre.

“It was a fairly quiet issue before that,” Lisman says. “It had gone long enough… A lot of the members of RMSA are confused and shocked that there hasn’t been a result.”

The first solution was put forth to the administration in a joint effort by RMSA and RyeSAC. They proposed renovations to knock down walls and expand the Multifaith centre, which Creery rejected in October as unfeasible, Lisman says. Creery put a $15,000 price tag on the renovations and suggested a portable microphone instead. The second proposed solution, the use of the lower gym, was again rejected under the university’s policy of being secular.

In late November, Toronto Raptors star Hakeem Olajuwon sent a letter to Ryerson’s administration in support of the students’ request. During Olajuwon’s lengthy career in Houston, he was a very visible member of the Muslim community and his advocacy has continued in Toronto since joining the Raptors.

In January, RMSA sought an outside mediator. Abdul Hai Patel, a chaplain at the University of Toronto and a commissioner with the Ontario Human Rights Commission (though his proposed mediation was not as an agent of the OHRC), agreed to intervene and try to open a dialogue. About a week later, Grayson and the administration rejected mediation.

“After much reflection, the university must respectfully decline your offer,” Grayson said in an e-mail to Khan. She later questioned Patel’s objectivity, noting that he is an Imam, the Muslim equivalent of a minister.

Also in the e-mail, Grayson cited a “Christian group” that was turned down in a similar request for on-campus space. She later identified this group as St Philip Neri House, Ryerson’s Catholic Chaplaincy.

But Neri House executive director Claudia Brown says the chaplaincy decided to stay off campus because, after seeing the too-small Multifaith centre, they wanted a bigger facility with permanent office space. They settled at 64 McGill St., behind the theatre school building.

Grayson also reiterated the solutions the university proposed — solutions that have been dismissed as chipping away at the corner-stones of Islam.

Patel says he is surprised by the university’s stance.

“I’ve never heard of this happening anywhere else in North America,” he says. “Every university does it (accommodate prayers).”

At the University of Toronto, he says Muslims are allowed to pray in spaces such as Hart House if the designated religious rooms are already booked or too small.

While other schools may be open to providing non-religious space on their campuses for their Muslim students, Ryerson’s administration seems to have dug in its heels. Lisman and RyeSAC say they will keep up with the fight, though RMSA president Khan seems ready to take his leave, frustrated by a fight that’s going nowhere.

While taking the steps of filing a human rights complaint is a large one and a lengthy process, he says RMSA is left with little other choice. The process is starting slowly. RyeSAC and RMSA have circulated hundreds of petitions calling for support and about 60 have trickled back in. But on Friday afternoons, shoulder to shoulder in the cramped lounges of Jorgenson Hall, Ryerson’s Muslim students are unfazed in their search for a place to pray, despite the staggering roadblock crafted by the Ryerson administration.

Leave a Reply