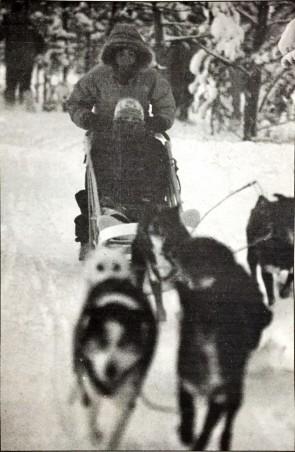

Ryerson journalism grad Jennifer Kwan tells the harrowing tale of northern initiation, courtesy of an errant dog sled and some pups on thelam

The musher is calm. The dogs, with their crooked eyes, are barking, lunging forward and eager.

Yup, yup, yup. C’mon boys!” Kiara Adams calls out.

The ground begins to crackle and we start to glide. Fifteen-year-old Adams is sitting atop the sled on a tattered frozen, blue and beige seat cushion.

A month ago, I could’ve been spotted skipping down Toronto’s College Street on a balmy night.

Here, up in the Yukon Territory, I’m surrounding by howling mutts and men with frosted beards who don rubber Sorels.

The approximately 3.5 kilometre media sled dog race is an annual event that gets “Cheechakos” (a term used to describe someone who has yet to experience their first winter in the Yukon News, my editor thought no other event could’ve topped it.

He was right.

It may not have been the 15 to 17 hour days one puts in to compete in the infamous Yukon Quest International Sled Dog Race, a 1,023-mile race throughout Alaska’s Interior and the Yukon.

But I’m standing on a pair of skinny runners — wooden planks that are about two inches wide — gliding on a dog sled behind some sort of mushing wunderkind.

Gee, gee. Ha, ha. Whoa. These three calls start running through my mind as we gain speed.

The first one means bank right, and the second means the dogs will curb left. The six dogs that are harnessed side-by-side will (more than) likely stop, if I bark the last call.

Quick lessons: Put lots of weight on the other side when you lean, or you’ll tip the sled. To slow the dogs down, use the track. Use the claw break to stop. This is the snow hook, be very careful with it.

My feet feel sturdy, my hands clenched around the handlebars. The black fleece balaclava around my face feels snug, and I’m wrapped in a down parka with a now icy faux-fur trimmed hood.

The ground becomes bumpier, and the course more windy. I watch the dogs closely and follow their lead as they traverse the frozen terrain.

Instead of calling out, Adams, who is still sitting directly in front of me with her feet turned out, drops her hands to the right or left signalling for me to shift my weight back and forth.

Slowly, I rise from my hunched over position as we enter an open space on the Annie Lake golf course, which is located 30 kilometres south of the city of Whitehorse.

Around me, the sunlight gleams against the untouched, powdery snow. Even at -28 degrees, the scene was breathtaking.

“I thought this would be a nightmare,” says Adams, as we head back into the bush. “But you’re getting the hang of it.”

It’s as if the comment is an omen.

Seconds later, we approach a sharp corner. The dogs run right. I lean right. The tree trunk gets closer.

“Lean… lean, lean, lean… lean!” Adams screams. Her right arms is stretched way up, and to the right.

I lean hard to the right. The tree trunk is too close. Gee, gee… Ha, Ha… Whoa… Quick lessons.

The force of the hit rams the handlebars into my chest, and whips my head forward then back.

It drives Adams into the tree, and dents the dog sled in the process. The snow covers us, blinds us.

“My dogs, Adams exhales with desperation. “My… chest,” I think to myself.

Stunned, she looks down at the remaining four dogs. The force of the hit snapped both the leader-line and the tug-lines. Her leader-dogs are gone.

She grabs on to the reigns and starts to run. The dogs, still attached to the gear-line, follow her. We come to a second opening on the golf course.

“Risk! Rocky!” she screams into the air. “Risk! Rocky!”

It’s quiet. The once glorious scene of the sun flickering against the snow seems less spectacular.

Five minutes pass. The next team rides by. I wave. The other musher waves back.

Adams runs ahead of her dogs. They follow her. She stops, they stop.

“Yup, yup. C’mon!” she screams in a tired voice.

They stand almost perfectly still. Confused, they begin climbing over each other.

Another sled dog team rides by, and several others after that.

She untangles the lines and switches two of the dogs. Minutes pass, but they begin to move in unison.

Slower, they carry us back across the finish line. A small, clapping crowd greets us.

“Did my dogs come back?” Adams hollers.

Risk and Rocky are back, chained to the metal railing of a truck.

They too are excited for their next race.

Jennifer Kwan’s northern primer

North of 60: The Yukon Territory is bounded north by the Beaufort Sea of the Arctic Ocean, the Northwest Territories to the east, and southwest by Alaska and British Columbia. It is comprised by primarily 16 communities with a total population of 30,418. Of that number 22,583 live in the capital city of Whitehorse nestled on the Yukon River.

The weather and such: On average, the temperature can peak above 20 degrees and dip as low as -40 degrees. In the summertime, the average hours of daylight is between 17 and 20, and in the winter it is five.

Common geographical blunders: What’s it like in: Whitehorse, N.W.T? Whiteknife, Y.T? Whitehorse, Alaska?

Cheechako, Sourdough and Yukoner: Hierarchical terms used to define the territory’s population. Someone new to the territory is called a Cheechako. After that, they graduate to Sourdough status. Yukoners can often be identified by the number of cracks on the windshield of their car, or if they’re spotted driving less than a block to get from points A to B.

Sourtoe Cocktail: Akin to the game of “I dare you to…” it’s more like “I dare you to… do the toe.” The “toe” is a pickled toe that was most likely lost, by most accounts, to frostbite. The purpose is to dunk the toe in the alcohol of your choice, and sip the drink until the purplish thing brushes against your lips.

Outside: A term used to denote anyone, for whatever reason, who moves to the Yukon. Conversely, it’s commonly used to describe what happens outside of the Yukon.

Most common Q & A: What brought you to the Yukon? Answer: I came here for one year, and ended up staying for 17.

Leave a Reply