They’re not little, they’re certainly not green, and they’re not all men; but if they have their way, they’ll be the first Martians you ever see. And they’re about to descend on Ryerson

By Colin Hunter

Deep in the medieval-themed basement of Toronto’s Lillian Smith Library at College and Spadina, eight members of the local chapter of the Mars Society quibble over plans for their upcoming national conference at Ryerson Feb. 16. Like any committee planning an event, they discuss mundane matters such as who will run the registration booth, who will handle audiovisual equipment, and who will sell t-shirts. Behind such trifling details, though, is a far more profound motivation: these people are determined to be the first earthlings to colonize Mars.

The group is one of more than 30 chapters around the world under the guidance of the Boulder, Col.- based Mars Society.

The organization is the brainchild of Dr. Robert Zubrin — a former engineer for Lockheed Martin. Under Zubrin’s unswerving vision and his devotion to the Mars cause, the society has swelled to more than 3,500 Mars enthusiasts, including such notables as director James Cameron and NASA moonwalker Buzz Aldrin.

While individual chapters of the Mars Society vary in size and activities, all are bound by a shared desire to boldly go where no man has gone before: the Red Planet. And they don’t intend on a short visit; they plan on staying there.

“We don’t just want to plant a flag, make some footprints and come back,” says Rocky Persaud, a U of T geology student and founding member of the Toronto chapter. “We want to go there for good.”

These lofty aspirations have been backed by some serious investments in pre-Mars research. Persaud was among one of the first crews to live at the Mars Desert Research Station, a simulated Martian habitat, located appropriately in a barren Utah desert.

“It’s a mock-up of a station for astronauts on Mars to live in,” Persaud explains. “It’s got two decks, airlocks, a lab, workspace, and habitation rooms for a crew of six. It’s there to help us understand how science would be done on Mars.”

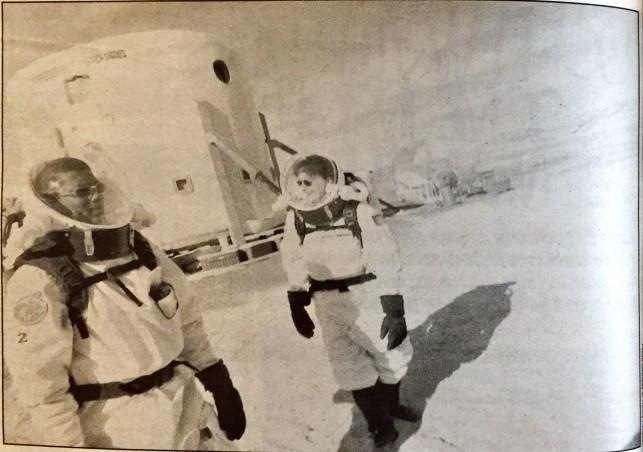

Persaud and crewmates would don mock spacesuits and venture out of the cylindrical habitation module (lovingly referred to by its crew as the “hab”) to collect rock and soil samples.

“We wore ski gloves to get a feel for the movement restrictions real Mars astronauts would face.” Other restrictions of interplanetary travel, he admit, did not always apply. “We could, of course, just go for a drive into town now and then.”

Along with Persaud in the Utah “hab” was Anna Paulson, an engineering student at the University of Michigan who will be speaking at this month’s conference. Paulson is the manager of the Michigan Mars Rover Project, a privately funded program aimed at creating a kind of Martian motorhome to be used for research treks across the planet. Though her current rover is strictly earthbound, she hopes that a future model will trundle across Mars, preferably with her in it. “My primary interest is in building industry in a new frontier, and I plan to be one of the first people on Mars.”

The road to that new frontier begins closer to home than you might think. The Utah “hab” has a northern sister — the Flashline Mars Research Station (FMARS) on the wind-whipped polar desert of Devon Island in Nunavut. Because of its isolation, this arctic pseudo-Mars could benefit from a more centralized mission support station; if Ryerson student Brian Orlotti gets his wish, it will be right here in Toronto.

When Orlotti was volunteering at Mars Society headquarters in Colorado last summer, a senior member in the organization asked him if the Toronto group could create a communications way-station for signals from the Arctic hab. The group voted unanimously to give it a try.

“Communications to and from FMARS on Devon Island will filter through the Toronto mission support station,” Orlotti explains. “Scientific information on chemistry, geology, that kind of thing.”

Right now the mission support idea is just that — an idea. Orlotti and company are working to find sponsors to donate money, equipment and office space for the project. It is taxing and uninterestingly terrestrial legwork, but Orlotti never loses sight of the big picture.

“I believe that with enough work, we can get to Mars. If the political will is there, it can be done. The key is to generate the public support, which will in turn generate the political will. It’s an incredible opportunity for the human race.”

That notion — the Roddenberry-flavoured ideal that a mission to Mars is the next giant leap for mankind — is the prevailing motivation behind the Mars Society Simulations and seminars aside, all of the group’s would be Martians are driven by the idea that colonizing Mars is our race’s new manifest destiny. But the Mars Society is careful not to draw too close a comparison to the great colonisations of generations past.

“Sure, we want to go to Mars for essentially the same reason people wanted to find the West Indies and colonizes America,” says Craig Pickthorne, a Ryerson theatre student and Mars Society member. “Only now we don’t have anybody to conquer or any diseases to spread. It’s exploration without conquest.”

Orlotti agrees: “Some people see our goal as an extension of the colonization of North America. But the conquests of American were based on the morality of those times. There are stronger moral impulses in today’s society.”

So what, then, is it that drives the Mars Society toward their beloved red ball? What is the allure of hurtling through space in a tin can for months on end only to arrive on a lifeless, inhospitable, suffocating desert planet?

“Exploration itself has always had an allure for me,” Orlotti says. “Exploration of the unknown, looking over the next hill, seeing something that has never been seen before — that’s an inherent desire in all human beings.”

Pickthorne too speaks almost poetically of the prospect of a Mars mission.

“Just to be on another heavenly body, to look back on our planet as a whole, and to step onto another planet would be truly amazing.”

He envisages the quest for Mars not as an abandonment of Earth, but rather an opportunity to become better acquainted with it. “Looking at Mars is a way of looking at our own planet and learning how to help it. Most people speculate that Mars was once a warm and wet planet-like Earth, so understanding what happened to Mars will help us understand what is happening to us.”

One of the more hotly debated topics among Mars Society members is the concept of “terraforming” — the proposed introduction of an artificial atmosphere to Mars, making the planet green liveable. Mars devotees are divided on the matter; “greens” are those who support the idea, while “reds” would rather stay away from such Godplaying.

Orlotti, however, is unwilling to commit either way. “Right now, the question of terraforming is irrelevant. We haven’t even set foot on the planet yet. Let’s not put the cart before the horse.”

And he’s probably right; the giant leap to Mars will be made up of lots of tiny, earthly hops. After all, they still haven’t quite figured out who will be selling t-shirts at the conference.

Leave a Reply