By Louie Diaz

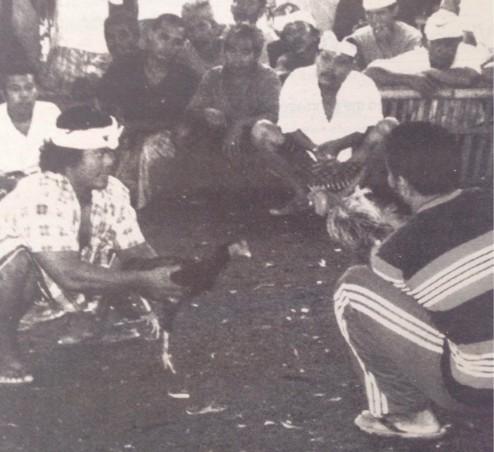

Two roosters attack each other as soon as the men holding them let go. They jump with their massive talons held high, ready to inflict the most damage. Feathers fly and the men of the village crowding the roosters shout and holler at the cockfight. On each rooster’s left talon is a sharp three-inch blade, tied on by red string. They fight until a rooster dies.

The white rooster is suddenly bleeding. Its neck hangs limp and red blood soaks its feathers. The other rooster keeps attacking, pecking at its wounded opponent. The white rooster, its neck bloodied, its feathers rumpled, refuses to die. Two men pick up the roosters. They place them in a small wicker dome cage where the victor will inevitably emerge.

The all-male spectators, only a few feet from the fight, stand shoulder to shoulder around the square ring, stretching their necks to see. There is no fence and there are no seats. The men up in the front squat, only an arms length away from the action. The white rooster is cornered in the tiny cage, helpless. It limps around, like its leg is broken. Its neck hangs on by what seems like a thin thread. Mercifully, the other rooster finishes it off. The men pay off their bets and the crowd suddenly disperses.

Cockfights are not uncommon in Bali, one of Indonesia’s 17,000 islands. Behind the countless vendors, bars, tourists, hotels, motels, restaurants, taxis, souvenir shops and temples is the real Bali — one full of strong Hindu beliefs, daily rituals and traditional villages. Cockfights are a small part of that life, the way horseracing is to North Americans.

Historically, they are part of traditional Hindu temple festivals. To appease the earth demons, during the festivals a purification ceremony is required — the ritual of spilling blood.

Cockfights are considered sacred and occur in sacred places, almost always adjacent to the village temple. The Balinese call cockfights tabuh rah, or the spilling of the blood. Cockfights may have originated in blood sacrifices and religious beliefs but today they’re more about gambling and entertainment.

The arrival of spring also marks the arrival of the New Year in Bali. It is an important religious event called Nyepi (The Day of Silence). The day before Nyepi, cockfights take place all over Bali. The Balinese believe blood spilt from the fights will cleanse the impure earth.

In 1926, Dutch settlers in Bali outlawed the sport. The central government in Jakarta also banned it in 1981. The mostly Muslim nation of Indonesia forbids gambling as it goes against the teachings of Islam because it believes cockfights are causing moral decay and corrupting the Balinese. However, both found it very difficult to enforce their laws as cockfighting remains a common practice.

Norman Taylor, director of Animal Alliance of Canada, says that the practice of cockfighting is inhumane. He has witnessed cockfights in Peru, where they have similar rules to Bali. “It is not a ritual if it’s the slaughter of two animals,” he says. “Why do we have to torture them in inhumane ways?” Taylor says that even though it may be part of religious ceremonies it goes against the Hindu tradition of respecting animals. “It is unacceptable to us.”

Arne Kislenko is a Southeast Asian historian at Ryerson University. He says that cockfighting may be widespread but it doesn’t mean that it’s culturally significant in Bali, of anywhere in Southeast Asia. “It may have started as a ritualistic practice but now it’s more of an underground gambling practice,” Kislenko says. “It’s a large stretch from saying they like cockfighting to saying it’s an integral part of culture. It’s a practice in society more on par with illicit things.”

Balinese men still spend a lot of time with their prized roosters, trimming their feathers and combs so they don’t provide a beak hold for the opponent. They feed it a special diet of grains, chopped meat and jackfruit, which supposedly thickens the cock’s blood. The offspring of a champion rooster is worth more than any ordinary bird.

The best roosters are imported from the Philippines, another hotspot for cockfights. They have bigger talons than normal roosters, are sleek and slender and have abnormally large wings. These wings are important during fighting because they let the rooster attack from a higher vantage point, thereby increasing the chances of landing the fatal blow with the razor sharp blade, called a taji.

Today’s cockfight is a special one, held only twice a year in conjunction with the village procession to their temple, built in 944 AD. A woman represents every family from the village and they all wear the same special clothes for the occasion — a white blouse and dark gold sarong. Every woman has an offering of food and fruits balanced on their head. They are arranged into elaborate, ornamental centrepieces. About 40 women walk single file, each with different arrangements, an awe-inspiring show of faith.

The cockfights take place after the parade of villagers make their way into the temple. The men come carrying their roosters in a bag around their shoulders. They sit in a circle and the owners caress and massage each animal, sizing up each rooster. The owners want to pick a rooster that is of similar weight and stature as his own. They also look at the colour of the bird’s feathers, the size of their bodies and legs and the size and strength of their talons. This will hopefully create a fair fight. Once the two owners agree on a reasonable fight, the men clear the ring.

Only two men are left. Each holds the rooster, strokes its tail and head. They spread its wing and show the crowd what kind of animal they have.

To incite a rooster to an explosive fury they will pull its tails, ruffle its feathers and eve stuff red peppers down its throat. Then the audience explodes and it seems as if everyone turns into a Wall Street stockbroker. Everyone starts to shout at one another, looking for bets. Gamblers use hand signals to tell which rooster they want to bet on and how much they want to wager. Using this type of complicated hand gestures is subject to its own rules. Different gestures — waving your hand or pointing your fingers in a downward direction — can have a wide range of meanings. Eye contact is enough to lock a bet. Bets have to be made before the fighting starts. It’s a mad frenzy as men push each other shout and try to get the attention of everybody else.

The fight ensues and the winning owner, as tradition dictates, will get the losing — and consequently now dead rooster — to bring home to his family to eat. Money is exchanged between the men to honour the bets. The winning roosters get to go home, injured perhaps, but alive enough for another fight.

Leave a Reply