By Adam Button

Ryerson computer science students can’t understand why professor Anastase Mastoras isn’t teaching the courses he’s taught for more than 10 years.

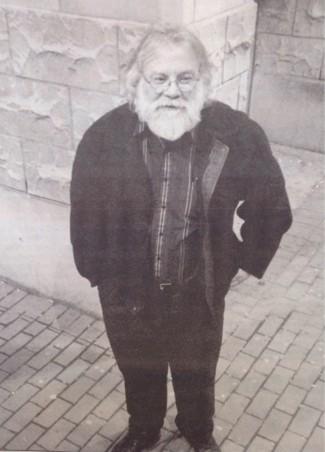

Mastoras is a full-time, tenured faculty member. His students love him. He is full of passion. He dances around lecture halls and empathically belts out his ideas. They say the 57-year-old is from a generation where people didn’t gloss over mistakes. “When you’re wrong he tells you that you’re wrong,” says Lukasz Wawrzyniak, a recent grad who says Mastoras was his favourite teacher. Last year, nearly 200 students nominated Mastoras for a teaching award.

Now those students have started to launch petitions because Mastoras isn’t teaching four of the courses he did last year.

Mastoras says he has the same time table for 11 years. “I love those courses,” he says. Some of the classes didn’t even exist before Mastoras invented them. Before, Mastoras taught five day-time courses every year. Now, he’s teaching two.

The only explanation to come out of his department is that Mastoras’ hours were cut back because he taught two to three extra hours every week — what the school calls overload. Mastoras says overload is common. “Everyone makes four hours of overload,” he says. “Two hours is nothing.”

A more probable explanation is that Mastoras lost the courses due to a backlash from conflict between him and a group of his students last year. Mastoras accused the students of cheating on a project, but they managed to pass the course by appealing their marks on the ground that the course was poorly taught.

According to the experts on the appeals process, that academic appeal could not have succeeded unless the plagiarism was addressed — it wasn’t. Now, computer science administration has removed the popular professor from some classes.

In the fall of 2001, Mastoras was teaching an extra night school course called CCPS 510 Database Management Systems, that centred around designing a database for a fictional catering company. It is one of the most advanced computer science courses at Ryerson. Twenty-one students were in the class, many of them working professionals.

Brian Gordon was one of those students. He designed software for the CBC Web page, but he wasn’t really the computer science type. His education included a masters degree in English literature from the University of Toronto. He was in the class because he liked learning.

Gordon says that in all of his years at school, he’s never had such a bad time in a class. “The teacher was a terrible teacher,” he says of Mastoras. “He only copied his notes to the board and his notes were illegible, incoherent and full of mistakes.”

Gordon felt like the class was a rip-off. He says the lectures were too short and the teaching assistants didn’t do their job. Most of all, he disliked Mastoras.

“It was impossible to learn from him,” he says. “He was very insulting.”

Gordon considered writing a petition.

At the same time, eight students in the class were being accused of plagiarising the final project by the two teaching assistants and professor Mastoras. Teaching assistant Alfredo Berardi remembers it.

“We collected the paper work and went through it — the two TAs and Mastoras. We read them in a cycle, each going through them.

“In one paper I noticed a mistake, then when I grabbed the next paper by luck I flipped it to the same page. I saw the same error,” says Berardi.

The project was about two hundred pages of programming code.

“That never happens,” Berardi says. “The exact error doesn’t happen unless you’re completely copying.”

When the TAs further inspected the assignment, they realized the eight students (who were in two groups of four) had copied a paper from the previous year.

“It was strictly copy and paste,” said Berardi. “We all agreed it was plagiarism. Mastoras asked us if we all agreed. It was without a doubt — still is.”

They reported the plagiarism and sent the assignments to the interim chair of computer science, Alain Lan. It’s his job to determine if the students cheated. The students were notified that they had been accused of cheating.

Meanwhile, Gordon decided to follow through with his complaint. He brought the letter he wrote to class and asked his classmates to sign it. There were a variety of complaints: the lectures were too short, the teaching assistants were unhelpful, lecture material was poor, the midterm was on the same day that part of the project was due, and Mastoras pressured the class into having the final exam two weeks early.

Gordon says 13 people signed his petition in the class of 21. But Mehul Patel, who was in a group with Gordon, says only four people signed it. Gordon wouldn’t allow The Eyeopener to verify the number.

“He approached me to sign the petition about his view of the lack of clarity of the course,” Patel says. “He told me what he thought. I told him I understood the course and liked the course.”

Another student, Ali Taleb, says he was outraged by Gordon’s claims. He wrote a point-by-point counter-petition, which alleged misbehaviour and absenteeism among the people who complained.

“In closing,” it reads, “we believe that this is a high level and high quality course and as students we must truly work hard to pass with good academic standards. The course was taught, managed and delivered in a very qualitative and professional manner.”

Taleb says he only asked 10 people to sign his petition and they all did. He too refused to provide a copy for The Eyeopener to verify his numbers. He says he lost the signatures.

Both petitions were sent to John Hicks, the director of continuing education for engineering and applied science. He acknowledged that he received the petitions but wouldn’t verify the number of signees.

Gordon failed the course; he says it was because he complained. Several of the people who signed his petition also failed or got low marks. Gordon thought that was because the signed the petition. The alleged cheaters never told Gordon that their marks were because of plagiarism or that they signed the petition after they were accused of cheating.

Gordon thought the low marks were proof that Mastoras discriminated against the people who signed the petition. He appealed his grade on the same grounds as his complaint. The students accused of plagiarism also appealed their grade on the same grounds as Gordon’s complaint. None of the appeals ever mention plagiarism, yet two months later, administration called Gordon and said everybody won: Gordon would get a refund and the alleged cheaters were offered A’s and B’s.

Appeals in the computer science courses all go to Alain Lan, the department chair, who makes the final decision alone.

Ryerson recently debated changing the appeals process so all appeals would go to a committee instead of the chair, but decided against it, saying it would create too much bureaucracy.

The teaching assistants were stupefied when they learned of the decision. “You can’t avoid cheating,” Belic says, “But administration can’t let people get away with it.”

What upset them even more was that they were never allowed to defend themselves.

“They just took their word,” said Berardi. “I was never contacted.”

Berardi says that he only learned the result of the appeals when Hicks called him and informed him that his pay was suspended because of his conduct in the course.

Diane Schulman, the Secretary of Academic Council, says cases of cheating couldn’t be overturned by appeals like the ones in CCPS 510.

“Bad course management doesn’t exclude plagiarism,” she said, adding that she had never heard of a case where that happened.

According to her, the people implicated in an appeal including TAs are supposed to be allowed to defend their actions. Because the appeal did not address the plagiarism, it couldn’t have succeeded.

Lan refused to be interviewed about the appeal despite numerous requests. He said it was confidential — the case was closed.

John Hicks, whom the petitions for and against Mastoras were addressed, wouldn’t talk about the appeal. He says he had no comment on why the TAs weren’t contacted or why their pay was suspended. In a statement he wrote: “I will say that this was a very complex issue, that involved several university policies and processes, and not just the appeals process.” He would not comment on the other processes involved.

The dean of continuing education, Marilyn Booth says she didn’t play a part in the appeal but became aware of it and ensured that all the standards were met.

“I guess I believe that every student deserves to have the best possible learning environment,” she says. “They deserve to have the course management policy lived up to and they deserve to have what they pay for. I’m not going to talk about this appeal.”

Lan, Booth and Hicks all said they couldn’t answer questions about the appeal because it was confidential. It’s a system that’s designed to protect students, but it is also a way for administrators to avoid answering for their actions. There is no safeguard in the appeals process. No one reviews these decisions.

Professor Mastoras also says he can’t comment on the appeal or the plagiarism, because he fears it could cost him the remnants of his job. He did say that he wants his courses back.

“They’ve destroyed the course,” he says of CCPS 510. This year is the first time in 11 years someone besides Mastoras has taught the course.

“All I can say is that I was disappointed about how the administration handled things, very deeply disappointed,” he says.

Students are also disappointed that Mastoras is no longer teaching his courses. They’ve written at least six petitions asking for him back. There was one for every class he’s lost and several for additional continuing education classes. Over the summer, administration even shut down an Internet petition.

Lan wouldn’t respond to questions about why Mastoras was no longer teaching the courses, but Gordon indicated it was because of the appeal. When he found out he won his appeal he was told Mastoras wouldn’t no longer be teaching the course. “What I was told verbally was the Anastase Mastoras, the professor, was not going to be teaching that course anymore,” Gordon said.

Former student Lukasz Wawrzyniak says that Mastoras’ style might have rubbed a few people in the class and the office the wrong way.

“People want praise for their mistakes,” he says. “If you make a mistake he’s going to tell you.”

Exchange student Arfan Chaudhury called Mastoras a “wonderful professor.” He says he don’t forget the things Mastoras taught him for the rest of his life.

“It would be a great loss [if Mastoras was no longer at Ryerson],” he says. “I feel very strongly for that.”

Wawrzyniak can’t understand why this has happened to Mastoras. “How is it that they listen to this one English literature student and they don’t listen to all the petitions people have been writing for him?”

Leave a Reply