By Julia Nowicki

Sarah Taylor* watched herself throughout the night as she sat at the dining room table. Across the room was a large mirror hanging on the wall, documenting her decay. In the mirror she saw her tan skin turn pale, and she thought she could see the blood moving through her veins and across her face. Her eyes had sunk into her skull. Taylor wasn’t staring at herself, but at a ghost. She doesn’t remember the last time she ate; her appetite was completely gone. Even coffee was a struggle to get down. She was not sure how long it had been since she had sat down. It could have been 15 minutes or 15 hours. The only thing she was interested in was her work. In front of her was her computer, and on it an essay that she had been working on since 9 p.m. that night. She had taken a high dose of vyvanse, a medication normally used to treat attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD). She took double the amount that should be prescribed.Taylor recalls what had led her to this situation today, almost two years later. At the time, inexperience and a lack of effective time management, coupled with a full-time job, created the perfect storm for procrastination. It was the first exam season of her bachelor of journalism degree and she was afraid that she was running out of time to finish everything she had yet to do.

The deadline for her environmental politics essay was just a couple days away, and she had barely started writing. Earlier that night, Taylor had determined that the drug was the only option for her amidst the stress and distractions that prevented her from completing the essay sober. She had called her friend who dealt his prescription vyvanse regularly to desperate students.

That’s how she describes her situation now—desperate.

The number of students misusing prescription drugs for the sole purpose of getting ahead in their studies is substantial. It poses an issue, not just medically, but ethically. When students are willing to sacrifice their health and well-being for a grade, universities are facing an issue far more complex than what it appears.

He was searching for an edge, something to drown out the noise, the doubt and distractions

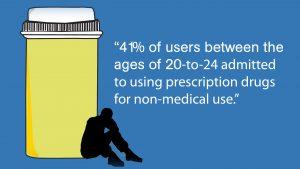

Youth aged 15-to-24 were the most frequent users of psychoactive pharmaceuticals for non-medical purposes, according to a 2015 study by the Canadian Tobacco and Drug Survey conducted by Statistics Canada. Stimulants like adderall, vyvanse and ritalin, which are normally used to treat ADHD, were found to have the highest misuse rate, with 41 per cent of users between the ages of 20-to-24 admitting to using such drugs for non-medical purposes.

Vyvanse, the drug that Taylor had used to help her get ahead in her class, is a derivative of amphetamine, similar to adderall. Amphetamines are known for their upping effect and highly addictive properties. When similar drugs are bought and sold illegally, they’re called speed. Ritalin is derivative of another highly addictive and well-known party drug—cocaine.

Using a stimulant drug similar to cocaine to aid studying may seem counter-intuitive, but Dr. Todd Girard, a psychology professor at Ryerson, said that it all depends on which areas of the brain are activated when the drug enters the bloodstream. Girard has been researching the effects of recreational drug use on cognition and intelligence, and says the main chemical that causes most primary effects is dopamine, which is increased in the brain while on these medications.

Dopamine can boost focus and increase confidence while targeting one specific region of the brain.

“There are a number of different dopamine systems in the brain, but the key one is what we call the Incentive Salience System. Incentive, in this case, means something that the person may want and salience means that it might be important,” Girard said.

In other words, taking vyvanse triggers the brain so that whatever the individual is working on seems important to them and requires their full attention. In someone who has ADHD, this system is deficient, meaning it is not functioning at the same capacity as someone without ADHD. Ritalin, vyvanse and adderall in these cases help normalize that specific brain region and bring it up to working capacity, for people without ADHD it kicks it into overdrive.

Using drugs like this begs the question as to whether using medication not prescribed to you for any diagnosable medical need should be considered a form of academic dishonesty or cheating. In section 12 (b) of the Ryerson University student code of non-academic conduct, it states that students “must not possess, provide, or consume illegal drugs.” Possession of a schedule 1 drug—such as vyvanse—is considered illegal, with severe criminal penalty. However, in terms of academic misconduct, senate policy 60 on academic integrity does not explicitly state that the use of non-prescription stimulants, or medication in general, is considered a form of cheating.

Studies have yet to prove that stimulant medication actually enhances higher-order cognitive properties like memory, so the idea that these drugs are making you smarter may be a stretch. And studies, like the meta-analysis done by the Center on Young Adult Health and Development at the University of Maryland School of Public Health, found that non-medical prescription stimulant users tend to have lower average GPAs than non-users.

However, what that study had also found is that students who use these medications may be at risk for developing addictions, and are more prone to taking other drugs, signifying a larger problem for the student population down the line. Universities need to find a way to minimize addiction-causing behaviours beyond what services they currently provide, and find ways to help students who use highly-addictive medications rather than just penalize them.

Jake Harrison* doesn’t remember much from his microeconomics exam, just that it was a typical chilly December night when he got out. The snow was pretty heavy that year, but luckily the sidewalks had been shovelled around campus. It was probably his third final in the fall exam season. It was late, around 8 or 9 p.m. The sun had set hours before and he walked in the dark to the bus stop. He was only focused on one thing: getting home and getting to bed.

The exhaustion he felt was overwhelming and he was spaced out from the fatigue of writing and studying for his exam. The cold air numbed his skin to the point where he couldn’t feel his glasses resting on his nose. In a moment of panic he swept his hand up to his face, thinking he may have forgotten them in the exam hall. He hadn’t left them, but instead knocked the glasses off onto the hard concrete below. He looked down and sighed in self-pity. Picking them up, he continued on and stood in line at the bus stop, waiting to start his hour-long commute from the York University campus.

The shear physical and mental exhaustion is what Harrison remembers most from that exam season in December 2013, before he came to Ryerson. But he understood that was a pay- off from using vyvanse on a daily basis. It was a payoff he was willing to take. Although he is currently a successful Ryerson student, his time at York had been nothing short of troublesome. He had been expelled once before from the economics program there, and he was on the brink of a second expulsion after his first semester back at York.

“I remember sitting in my room on my bed. I had been studying for a couple of days already and I just wasn’t absorbing the material,” Harrison said. “I had a lot of trouble focusing. I felt desperate. I felt like I was going to fail, I was going to get kicked out again.”

He was searching for an edge, something to drown out the noise, the doubt and distractions, and help him focus at a time of great stress. He found that with vyvanse.

Without a legitimate medical need, students that are taking these powerful medications as a means to enhance their cognition, attention and memory are doing it without any regard for the short and long term risks they pose on their health. Students have come to understand that drugs like these can ‘work miracles’ when it comes to focusing on school assignments and studying, more than a simple cup of coffee might have done for them in the past.

Amphetamine use was popular long before the Controlled Substances Act in America (and the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act in Canada in 1996), which came into fruition in the ‘70s. The ‘40s and ‘50s saw an epidemic of amphetamine use among all ages and sexes, including college students, due to its liberal prescription by physicians. The Act in the ‘70s was an attempt to control and minimize the use of this drug, however, amphetamine use is again on the rise among students.

There is no doubt that the people who have used vyvanse in the past to study have found it to be effective in terms of enhancing their attention. However, once the immediate effects wear off, the consequences arise, and they come in the form of a crash.

“Instead of feeling like you have this boost of self-esteem, high alertness and positive energy, when you stop taking it you are going to feel a decrease in energy, low mood, depression, irritableness and a lack confidence,” Girard said.

A crash is temporary, and the hard recovery faced afterward is easily forgotten. However, with regular use, the consequences get much more severe and much more invisible.

Data is currently limited in terms of actual quantifiable effects with long-term stimulant use, but projects currently underway in the European Commission will hopefully shed light on the under-studied topic.

Data is currently limited in terms of actual quantifiable effects with long-term stimulant use, but projects currently underway in the European Commission will hopefully shed light on the under-studied topic.

However, studies have shown that dopamine can remain hyper-sensitive for up to a year after regular use of stimulant medication, Girard said. Not only that, but chronic misuse can lead to cardiovascular problems, increased blood pressure, gastrointestinal issues and—what could be considered the most worrisome—addiction.

Post-secondary institutions in Ontario have high rates of stimulant drug misuse when compared to the rest of the country, suggesting that this is a particularly unique issue facing universities and colleges, and one that they may not be prepared to tackle.

Statistical data across the country shows that only 0.2 per cent of all Canadians over the age of 15 have admitted to misusing a stimulant. However, the Spring 2016 National College Health Assessment, an online survey of 41 post-secondary institutions conducted by the American College Health Association, found that 4.5 per cent of students admitted to taking stimulant medication without a prescription.

The first time Taylor had used vyvanse, the side effects she experienced were the strongest she had ever felt before. They were most likely a result of repeated use, taking a large dose every 24 hours. After she took that first capsule at 9 p.m.—a capsule that had been tampered with and filled to the brim in order to make it more effective—she had stayed awake for the next 55 hours.

Her focus throughout that time was so intense she hadn’t noticed that her grinding teeth were actually grinding on the flesh inside her mouth. She only discovered days later that she had chewed a massive hole into the inside of her cheek. Her fatigue, by the end, was so extreme she experienced hallucinations to the point where she thought she was going blind. Ironically, after staying awake for so long, sleep proved to be extremely difficult.

That’s how she describes her situation now—desperate

“It’s the worst feeling in the world. To lie there feeling like every bone in your body is about to snap because of internal pressure but you know that the only thing that will relieve you is sleep and it’s not coming,” Taylor said. “It feels like it’s never coming.”

Yet this hasn’t deterred her from using the drug again. The essay she submitted came back with a high grade and she admitted that it was some of her best work. Almost every exam season since then, Taylor has been dependent on the drug to get her to perform her best during exams.

The challenge lies in the nature of the problem: they aren’t facing an addiction crisis but rather a dependency issue.

When students use psychoactive stimulants to study, and only to study, they fall into something called state-dependent learning. Although a student may not feel a physiological need for the substance, Girard said, they do run the risk of a deeper, more complex dependency.

Today, Taylor is a third-year student still attending Ryerson, and maintains that the drug is the only way for her to perform at her absolute best. She says that at the end of the day, if she could harness that level of control over her own attention, she wouldn’t need the drug. But in reality, she knows she can’t.

“It’s like trying to be as happy as you would on MDMA, you can’t. It’s impossible I think,” Taylor said.

Stimulants alter your brain chemistry to enhance focus and attention. Essentially, through repeated use, you grow accustomed to this specific state or chemistry balance when you study. Going forward, you may find that you learn better when on the drug, and alternatively when you try and study without it you feel like you can’t retain information or remember as easily as you would on vyvanse.

Currently, the Ryerson health promotion site, which has a variety of informational brochures on non-medical drug use and addiction, lacks information about prescription stimulant medication use. The only resource available for students fac- ing a stimulant dependency is counselling, but if a student is worried that their future at the university is in jeopardy, they may be hesitant to seek help openly.

Harrison sat in his philosophy class in Kerr Hall, his first class in the 2016 fall semester. After his second expulsion from York in 2014, Harrison decided to return for a third shot at a university degree. After taking courses for a year prior to enrolling through Spanning the Gaps, a program at Ryerson that helps students get back into school when it didn’t work out the first time, Harrison was enrolled as a full-time student in Ted Rogers School of Management. He still worries about his past, about the consequences his actions had on his future. He worries whether his diploma would be taken away if the school ever discovered how he managed to get by that one fall semester in 2013. How can you measure someone’s ability to get a degree? Is it cheating if you need it? Where do they draw the line? These are questions that still occupy Harrison’s mind.

The crowded lecture hall was filled with students, some of them probably much younger than himself, but it was not a concern. He was there only for one person—himself. The professor walked in and began the lecture. Adjusting his glasses, Harrison looked down to his notebook in front of him and began to take notes, writing along to the slow drone of the professor at the front of the class.

Harrison realized that day that this was his second chance to prove to himself and finally earn that university degree. This time he was determined to do it right, without drugs.

*Names have been changed to protect anonymity

Leave a Reply