By Marianna Lozowska & Skyler Ash

Nadar Chaves Dos Santos shows his ID to the receptionist, sits down and waits until someone summons him into a room with a round table. Other people are already sitting down. A woman comes in and begins asking him questions about his favourite frozen pizza. She quizzes him on brands, trying to get specific answers about the products. Talking about pizza goes on for hours, until finally, Chaves Dos Santos can taste a bite of a mystery slice. He has a slice of cheese, and a slice of pepperoni and bacon. Usually he orders his pizza with chicken or pepperoni, with extra BBQ sauce. But these were pretty good. And he got paid for it. “I don’t even know much [about the research], I just know I ate pizza,” Chaves Dos Santos jokes over the phone.

Before starting his job at a pet store, Chaves Dos Santos, a 21-year-old criminology student at the University of Ottawa, used to make money by participating in focus groups for products and advertisements. Chaves Dos Santos has been in nearly 10 research studies, each following a similar routine. His mom would find out about different studies and ask him and his brother if they wanted to participate.

The focus groups that he partook in varied from sitting in a row of seats with other participants watching a slideshow presentation and answering questions with a remote, to sitting in a circle with a group of people discussing the subject of the focus group. He’s tested out cereals and even got to try Trident’s layered gum before it hit shelves in Canada.

“It was mostly about the money. It would be like $55 an hour,” says Chaves Dos Santos. Sometimes if he stayed an extra 20 minutes, he’d make $75. “I actually got to try the things they were questioning us on, and then I was like, ‘OK, I definitely want to go back if I get pizza.’”

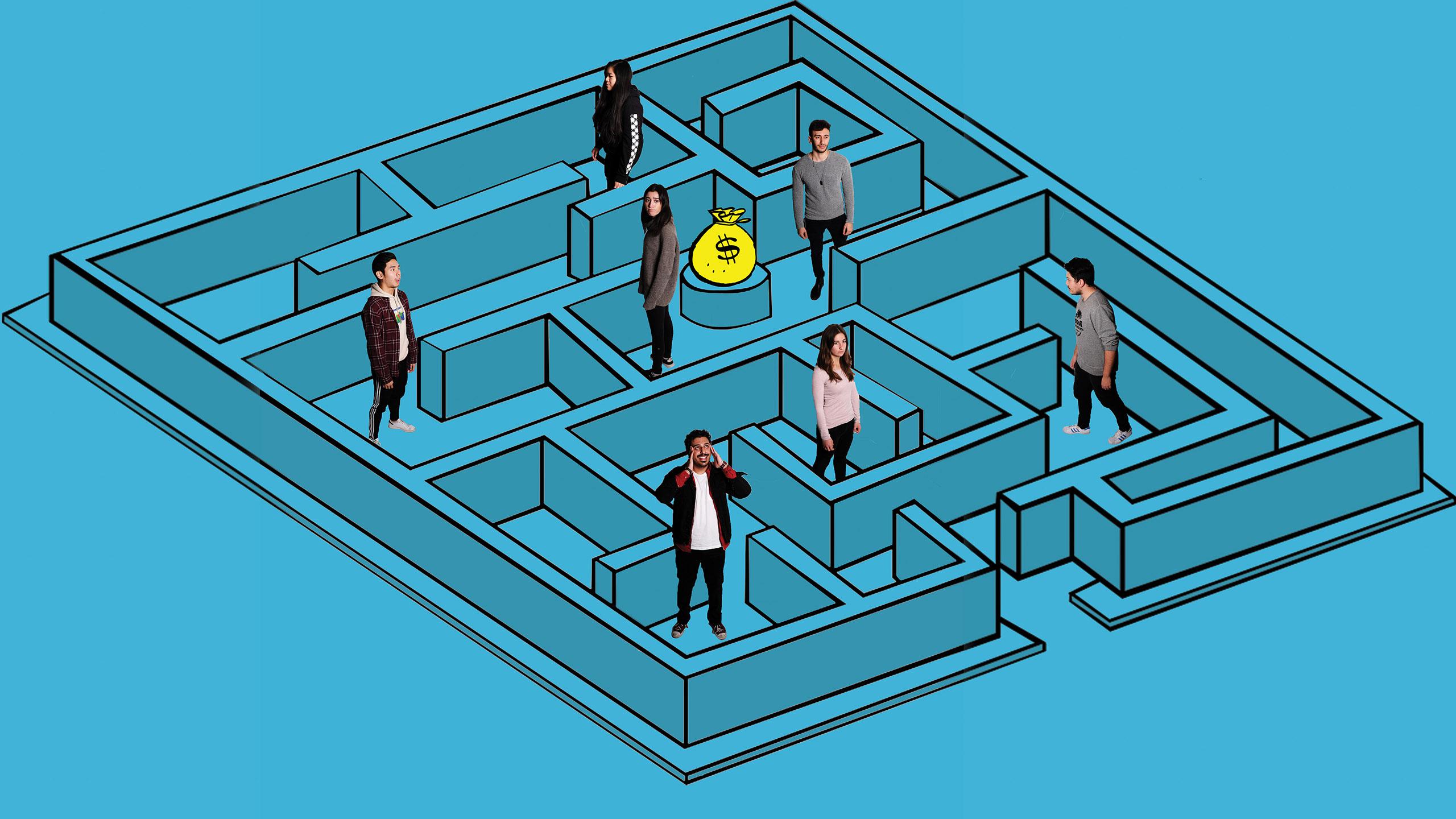

Chaves Dos Santos explained that participating in focus groups and research studies was an easy way for him to make a little extra cash, but not necessarily a way to fuel his interest in science or research studies. Research studies and focus groups are happening all the time, and some students are taking advantage of it. Sure, sometimes they are genuinely interested in the research, but for these students, it’s about the money. In a 2013 poll by Research!America, it was found that 78 per cent of people say that compensation was a major factor in why they chose to participate in studies and trials.

As a student or a recent grad, who couldn’t use a little extra cash? The Government of Canada reported that students paid about $8,248 for school, including tuition and student fees, in 2016. And if you live downtown, you’re paying an average of $2,000 in rent, according to the Toronto Real Estate Board’s 2016 report. So, sitting at a table for a few hours answering questions doesn’t seem like such a bad idea.

At Ryerson University, the psychology department has 31 research labs, each with the opportunity for someone to become a participant in the research. Sometimes the studies are advertised in newspapers, but usually they get exposure from word of mouth and brightly coloured flyers around campus, with questions like, “Are you a worrier?” and, “Are you a smoker?” taped to inside of bathroom stall doors.

She was told she would make $20 and be offered another free session, but because they were so behind, she made $200

Nick Bellissimo, associate professor in the School of Nutrition at Ryerson, says that compensation for participation in a study depends on what funding a project gets. Based on the quality of a study and the more invasive it is, the more money you will be paid.

The pay is usually minimum wage. “You’re not going to become wealthy by becoming a research participant in our studies,” he says. “[Students] would be very disappointed because the amount of compensation is relatively low.”

Bellissimo says that although Ryerson offers a variety of research participant opportunities, most studies only offer a course credit, rather than a monetary incentive. Although money does motivate people, Bellissimo says that participating in studies offers the individual a “trade-off” where they build their skill set instead of making money. “For a lot of people, what they tell us is they really want to be a part of the research process.”

Aliza Virani lays on a bed in a shockingly white room.

It’s her day off from work, and she decides to spend it a little differently than she usually does. There is a man standing near her, hands raised above her body, speaking to her in a calming voice. Around her are a few cameramen and a producer, documenting the experience. The man tells her to picture herself in a forest, in the mountains, in a calming place. But she doesn’t really follow along. His hands move above her body. It puts her on edge, and makes it hard to stay focused. This goes on for about an hour: the hands, the quiet, the cameras. She lays there with her eyes closed, and even falls asleep a few times.

Last week, while scrolling through Bunz, an online trading community where users can swap items and advice, Virani saw a callout for a reiki session. Reiki is a Japanese relaxation technique that uses a person’s energy to relax them and help heal. They were offering some compensation, but that wasn’t really why Virani said yes. After a car accident, she was left with some residual pain and she hoped this might help. In the same poll from Research!America, 89 per cent of people say they participate in trials and studies to see if it improves their health.

Virani was interviewed by the people running the study before and after her reiki session. They asked her what she expected, what she hoped to achieve and if she was experiencing any pain. They also took a urine sample before each of these interviews.

The study was running behind schedule that day, and Virani’s session ran four hours later than it was supposed to. She was told she would make $20 and be offered another free session, but because they were so behind, she made $200. Her friend came with her to keep her company, and ended up participating as well.

Since alternative medicine is not always covered under the Ontario Health Insurance Plan, this was an easy way to help her feel better, although she admits she didn’t feel much different after the session was over. But she enjoyed it, and would recommend it to others. “I like exploring things I don’t know about,” says Virani. “It was less so about getting paid. It was more the opportunity to try something new.”

This is something Katlyn Peck, who works at the Stress and Healthy Aging Research Lab at Ryerson, wants from her participants.

“I think people are motivated to do something that they are interested in but then also get compensated for it too,” Peck says. “I mean of course you’re going to have some in- dividuals that are purely motivated by the money. You hope not because you want them to be there for the right reasons, just a participant that wants to be there for the purposes of learning or the purposes of being there and experiencing [it].”

She has led many of her own research studies using SONA, an online website used by many universities to find participants for their studies.

Participating in focus groups and research studies was an easy way for him to make a little extra cash, but not necessarily a way to fuel his interest in science or research studies

Peck explained that through SONA, participating in a study or conducting one gives a student a course credit instead of a monetary compensation. Regardless of compensation, Peck says that participants were excited to join studies, much like Virani was.

Some studies that Peck conducted did compensate the participants. Peck explained that for a two and a half-hour study participants would receive a compensation of $30.

Peck says that although studies do not offer a lot of compensation, the experience itself is worth it. Both Belissimo and Peck say their primary research participant pool is comprised of Ryerson students. If a study requires additional participants, flyers are pinned across campus and in the surrounding area. Bellissimo says Ryerson wouldn’t be able to run their studies without all the help from people in the community who come to sign up.

Chaves Dos Santos shows up to the study and sits facing a screen. There are other people there and they are all holding remotes. They’re told that they need to rate what they see on a scale from one to five. Watching clips of fake commercials and company slogans flash by on the screen, he clicked in his answers. One. Three. Two. Three. He’s done this a few times. Nothing new.

When he started doing the studies, he didn’t care so much about the research. But sitting and listening to all the clicks from other participant’s remotes, he learns a lot about how people think. He notices that some people would just go along with whatever other people were answering but he felt that wasn’t honest, so he ignored them.

If he gave high scores, he didn’t have to stay longer. But sometimes he wouldn’t like what he saw on the slideshow, and would give it lower ratings. When he did this, he was asked to stay longer—they’d ask him questions about why he didn’t like it, subtly prompting him, and he’d have to watch the clips again and re-score them. He’d stay longer if he had to.

Why not? He’d get some extra cash for it.

Leave a Reply