By Urbi Khan

A study from the Ryerson Centre for Immigration and Settlement (RCIS) found that the Canadian media had an inherent bias when it came to the media coverage regarding Syrian refugees and, there needs to be a shift in the reporting narrative.

The study went on to highlight some key findings. One, the media often only gave a positive representation of the Canadian government and public as being humanitarian and generous, which the study termed as having “Canadian values.” The second point was that the media represented Syrian refugees as “lacking agency, and vulnerable and needy amidst challenges” and that the stories were gendered; Syrian male refugees were portrayed as security threats while coverage lacked female voices.

The report analysed stories from major Canadian news organizations including the Toronto Star, the Globe and Mail, National Post and Huffington Post. Youtube videos containing coverage from CTV and the CBC were also examined. The RCIS analysed 456 stories altogether from these sources. The study also discussed the political views of all newspapers and what each news organization was trying to achieve with their coverage of Syrian refugees.

The RCIS study determined that “Canadian citizens, politicians, and other public actors speak on behalf of refugees and exemplify a “saviour complex” that marginalizes Syrian refugees while offering a narrative of humanitarian and generous Canadians,” the report said.

It also concluded the media tended to paint private Canadian citizens as “saving the day” instead of focusing on the Syrian refugees who have been through many hardships.

Canada’s relationship and attitude regarding Syrian refugees

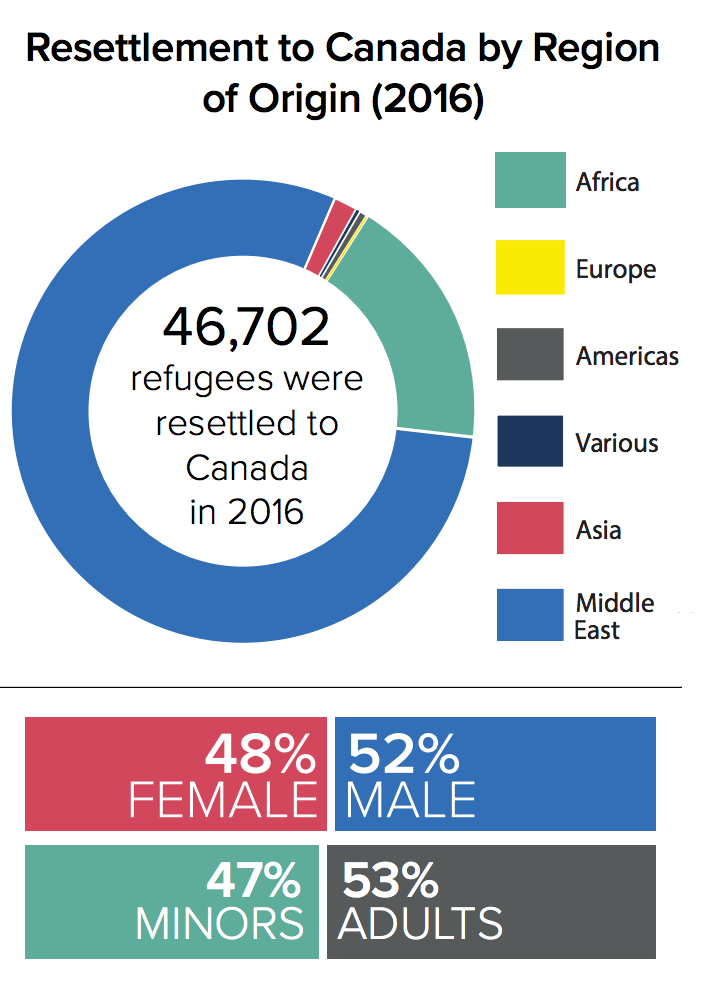

As of January of this year, there are a total of 40,081 Syrian refugees who have arrived in Canada since November of 2015, according to the Government of Canada. These include government assisted refugees, blended visa office-referred refugees and refugees who are privately sponsored. There are a total of 350 communities, not including Quebec, who have welcomed Syrian refugees as of December of 2016.

According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and the United Nations Refugee Agency, Canada has resettled almost 700,000 refugees since 1959. And after less than one year of resettlement, 90 per cent of Syrian refugees, in 2015-2016, have reported “having a strong or very strong sense of belonging in Canada.”

However, according to the Globe and Mail, a poll study conducted by the Angus Reid Institute (ARI) revealed that “Canadians do not appear to have unlimited willingness or capacity to continue to welcoming asylum seekers at current rates.” The poll study was based on public opinion and was conducted from Feb. 6 – 9 2017, after the Trump administration initiated a travel ban in the U.S.A. that barred Syrian refugees and other migrants from predominantly Muslim countries from coming into the States USA.

Just a reminder: predominantly Muslim nations have taken in 5 times more Syrian refugees than Europe, the US and Canada combined. In fact, Jordan alone has taken in more than those three combined. pic.twitter.com/Owo1CXQLie

— Christian Christensen (@ChrChristensen) October 16, 2017

The study focused on the political spectrum of Canada and America and how the American travel ban and how it affected Canada politically. The findings of the study shows a split in how Canadians have reacted to government approach to refugees coming in.

According to the ARI study, approximately half of the respondents, 54 per cent, voiced “doubts over whether refugee families make what they consider ‘enough effort’ to fit into Canada’s society”.

The study also found that 38 per cent of the poll respondents replied to “seeing some media coverage and having the odd conversation” and 28 per cent replied to “following it in the news and having discussions with friends and family” regarding Syrian refugees.

Asmaa Malik, a critical issues in journalism professor at Ryerson who focuses her research on media diaspora, said that the media coverage gives the impression that all refugee experiences are the same. She said they are not looked at as individuals with experiences but rather a group termed just as refugees.

Malik said that the target audience may reflect on the type of media coverage. For instance, she said that if the audience was predominantly white, they might want to see themselves reflected in the stories or see coverage of refugees trying to fit into a Canadian lifestyle.

She said that news organizations have not realized that their audience is culturally diverse, and that they “are still kind of having a very homogenous perspective and [I] think that [newsrooms] think their audience are like them.”

Regarding the RCIS study, Malik said she was not surprised by the findings. She said that what she found interesting was the “sheer number of reports that were not focused on the families and were focused on the people who were doing the sponsoring of the families” throughout the stories analyzed. Malik said stories on refugees should be centered on the refugees, themselves.

Malik also referred to Nicholas Keung, a Toronto Star reporter mentioned in the study who identifies as Canada’s longest-serving immigration reporter.

Keung is mentioned in the RCIS study as being a reporter who “goes against the general trend.” He wrote an article in the Toronto Star in December 2015, criticizing the media’s coverage of Syrian refugees.

“[T]hey came out of war, conflicts and atrocities. We need to promote their resilience and offer them proper post migration support. The big message here is resilience, not pathology.”

Malik agrees with this.

“I think we focus a lot on policy stories and not the people. Policy stories are about groups of people and I think the way we write about refugees should not be from a policy perspective.”

“I think we need a balance of policy stories and individual stories. For example, we can make a story about unemployment and refugees looking for jobs. Do not just write a refugee story.”

Syrian refugees have become “supporting characters” in their own stories

Kamal Al-Solaylee, a journalism professor at Ryerson, was mentioned in the study. In 2016, Al-Solaylee wrote an article in the Walrus regarding the coverage of Syrian refugees. He noted that, “the refugees were becoming supporting characters in their own drama.”

Al-Solaylee said that when the first wave of government sponsored refugees started to arrive, he noticed that the stories were not about what the refugees were experiencing or what their experiences left behind were, but they were about how generous and welcoming Canadians have been and “how Canadians are rising to the occasion to opening their hearts and their wallets to [refugees]”.

The stories should have been [initially] in the lines of: ‘let’s make sure that from a year from now this does not become an issue’

Al-Solaylee also found that when the stories were about Syrian refugees, they were about “soft subjects” such as the refugees dealing with their first Canadian winter and playing their first hockey game.

“It was like the media’s priorities were not about the refugee stories, they were about Canadian values stories and painting the picture of the white savior. And that to me was an issue,” said Al-Solaylee.

He also said that he received hate-mail in response to the article.

“When the Walrus story came out, I got tons of hate mail telling me that I am an ungrateful immigrant and ‘what’s wrong with Canadians being generous’ and I felt like people did not get my point. I did not say there was something bad with the generosity, but the issue was that’s the one story that the media picked to tell.”

Al-Solaylee believes that the biased coverage of Syrian refugees was “not done out of a place of malice” but to reflect a changing tide of attitudes towards immigration and “Canadian values” in the transition to a Liberal government from a Conservative one.

The media coverage has now changed to a more negative narrative from the initial “feel-good” coverage regarding Syrian refugees, according to Al-Solaylee.

“Now we are telling the stories that should have been told when the refugees first arrived,” said Al-Solaylee. “The stories should have been [initially] in the lines of: ‘let’s make sure that from a year from now this does not become an issue’.”

The problem for many refugees who haven’t found work is a lack of English-language skills. Another is having Syrian work or educational credentials that aren’t recognized in Canada. https://t.co/UsDoIwfXxQ

— CBC Windsor (@CBCWindsor) November 14, 2017

The media can pick and choose what stories are worth telling

Al-Solaylee believes that these stories about “soft subjects” came from a lack of research as “really hard stories do not come cheap” for newsrooms whereas “you can just get a camera and your phone perhaps and go out into the community where they are having a fundraiser for Syrian refugees and you make that the story.”

He also said that he thinks these news stories affect the public as they can develop “a misconception that Canadians can have regarding Syrian refugees and what they have experienced”.

“I come from the Middle-East and I know what these people have experienced. I know what it is like to be in a civil war and what it is like to have a family in the civil war. But the average Canadian may not,” said Al-Solaylee.

Al- Solaylee also talked about the focus on Alan Kurdi and how the devastating photo of the young drowned child surfaced and was a constant highlight in the media regarding Syrian refugees. Just as the Kurdi family became a staple in politics for the Liberal party in the plight to bring Syrian refugees to Canada, it became a staple in the Canadian media as well.

However, the media coverage silenced, quite rapidly, regarding the photo of a five-month-old Yemeni child, Udai Faisal , when pictured was just skin and bones in result of starvation, who had died in 2016, in result of the on-going Yemen war. Al-Solaylee discussed in a 2016 Globe and Mail article that empathy is opportunistic as white Canadians see more of themselves in Syrians.

Media coverage provides misconceptions about Syrians, not just Syrian refugees

Aya Baradie, a second-year journalism student at Ryerson, who is Syrian-Canadian, said that Syria is not entirely the way it is portrayed in the media.

Baradie said that the media coverage of Syrian refugees did not surprise her as “Canada has its fair share of dark pasts that have not been portrayed in a wholesome way in the media” such as the Japanese internment camps and the continued cultural genocide of the Indigenous peoples.

We have so much to be proud of and it just happens that the civil war is the only thing about Syria that people know about

From a personal point of view, Baradie said that Canadians do not realize the struggle that comes with resettling into an environment “where you don’t know the language the work environment or the people or the social norms”.

“I am Syrian and I know that there is a huge difference between carrying a conversation in Syria versus carrying one here,” said Baradie. “I went to Syria this summer actually and so I remember there was a culture shock, even though I am from Syria; I had to get used to it all over again.”

“Yes, we did a great job getting [refugees] here but what have we really done to help them fit in and survive.”

To those fleeing persecution, terror & war, Canadians will welcome you, regardless of your faith. Diversity is our strength #WelcomeToCanada

— Justin Trudeau (@JustinTrudeau) January 28, 2017

Baradie believes that there is a stereotype that accompanies her identity of being a Syrian-Canadian.

“Every time someone asks me where I am from, I almost always hesitate, sometimes. I just say I am from the Middle East and I like to say that sometimes because every time I have ever told someone that I am Syrian, I just get that, ‘oh I am sorry – I am so sorry that you’re Syrian and I am like why?” ” said Baradie.

“We have so much to be proud of and it just happens that the civil war is the only thing about Syria that people know about.”

The findings from the RCIS study and the opinions and proposed journalistic solutions from Al-Solaylee and Malik show that the Syrian refugee experience is much more complex than the media coverage portray it to be. The story focus regarding Syrian refugees needs to shift to the Syrian refugees’ experiences rather than the circumstances that surround them.

Jess

I would argue that many Canadians have an understanding of what it is like to immigrate to a country and not speak the language etc. It’s what the country is. People tend to see through the prism of their own experiences. My family had escaped war and a communist regime hell-bent on breaking their own people. Meanwhile at my university “Welcome to the Party” posters are sold, my family is privileged and people wear the hammer and sickle. Welcome to Canada, we all have gripes.

The news is a propaganda machine, and talking about how to alter public opinions using the news is just that. I understand that the intentions are precautionary counterbalances, but in the end, media diaspora contributes to lumping people into groups. Group-thinking is what gets you things like Japanese camps, Aboriginal abuses, and just about every brutality seen in humanity. The road to hell is paved with good intentions.