STEREOTYPES SAY INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS ARE ALL GUCCI AND PRADA. WE DISPEL THE OVER-GENERALIZATION AND LOOK AT FINANCES, POLITICS AND MENTAL HEALTH

Reported by: Zeinab Fakih

Edited by: Raneem Alozzi, Andrea Josic, Emma Sandri, Sherina Harris, Sarah Krichel and Kieona George

When international student Ali Amir* moved to Canada, he lived off-campus with two roommates in a studio with an extra room. In order to afford his living space, Amir had to share the one-bedroom apartment—but it came at the cost of his privacy.

He stayed with a distant relative for about a week, but left because he felt he couldn’t stay much longer. He wasn’t very close with them, and didn’t want the awkwardness.

At this point, Amir began his hunt for a place that he could afford while pursuing his degree at Ryerson.

“I’ve been in the worst living conditions as an international student. I didn’t know anyone here. It was kind of isolating,” says Amir. Two years later, things have not improved as Amir lives in a house with 12-13 people.

Originally from Saudi Arabia, Amir deals with much higher tuition fees than domestic students. Because of his financial situation, he says he felt “forced to stay in such accommodation.”

International students often face the stereotype that they’re rolling in cash. “It’s not an otherworldly assumption, because of the high cost of international tuition,” says Sharon Nyangweso, a consultant for communication and gender impact, with a focus on immigration. But that presumption—that international students come from wealth and can continuously afford living here—is toxic, says Sofia Descalzi, the national chairperson for the Canadian Federation of Students. The reality is that international students deal with many issues, including financial, political and mental health barriers.

In the 2017-18 academic year, Ryerson had 1,588 international undergraduate students, according to the University Planning Office. Zaheer Dauwer, a graduate of Ryerson’s immigration and settlement masters program, says international students have a major lack of support, on top of the financial burdens they face, making it difficult for some international students to settle into Canada.

As shown in Ryerson’s tuition breakdown, international students commonly pay more than triple the tuition of a domestic student, with international tuition increasing each year. For example, a domestic arts student pays up to $7,126, an international arts student will pay up to $27,627.

Within the past two years, Amir’s tuition has increased by about 71 per cent, rising from $21,000 a year to $36,000. In the engineering program for the 2016-17 year, Ryerson’s website showed that international student tuition ranged between $25,023 and $26,595. For 2019-20, the fees range between $28,882 and $36,610.

This year, Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s government applied a 10 per cent tuition cut for domestic students. Ryerson also increased international students’ tuition by 7.7 per cent in their proposed budget for 2019-20. According to the 2019-20 “budget priorities and expenditures” released by Ryerson’s Board of Governors (BOG) in April, applications from international high school students to Ryerson for fall 2019 was 12 per cent higher than the year prior.

Ryerson has planned on bringing in about 1,000 more international students in the next year. On top of this, Dauwer says international students are in a program where “they are provided with minimal support during their study period.” While he completed his master’s thesis in fall 2018, Dauwer heard from numerous institutions and learned that domestic students have a higher number of advisors in comparison to international students.

According to the April BoG report, Ryerson does not have any plans to provide more advisors in the accessibility centre or better informing professors on the reality of an international student’s life.

International students feel like they have to work harder than local students, communications student Kagabo Disi* from Rwanda says. “I don’t want [my parents] to feel like this money was wasted.”

These students must face difficult decisions, says Nyangweso. “[They are] working more than they are legally allowed to meet their basic needs, and working illegally for managers and bosses who exploit students’ various positions.”

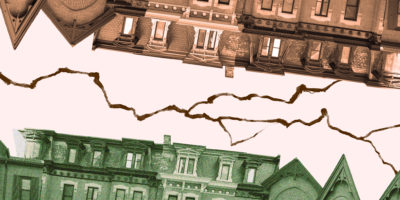

On top of tuition, international students, of course, deal with rent. The student housing crisis, Descalzi says, has a stronger impact on international students. According to a “September 2019 Rent Report” from Rentals.ca, Toronto takes the top spot for priciest rent in Canada—with the average cost of renting a one-bedroom apartment being $2,330 per month. In comparison, tenants in Vancouver are paying around $1,973 a month for a one-bedroom apartment.

The report also cites preliminary results of a survey that found Torontonians under 30 are spending an average of 49 per cent of their income on rent.

These students must also deal with constraints on the amount that they can work in order to make those end meet. According to the Government of Canada wesbite, study permits received by international students after June 1, 2019 indicate whether or not they are able to work off-campus. If so, these students are allowed to work up to 20 hours per week while their program is in session, and full-time during scheduled breaks. Domestic students do not have a cap on how many hours they can work alongside their schooling.

“Because they have a temporary status, some people may want to take advantage of that, and they become very vulnerable to being charged ridiculous amounts of money for rent,” says Descalzi. “[They also face] being expected to pay up to six months in advance—because that’s ‘how you do it in Canada,’ which is not necessarily true.”

Similarly, according to the federal government, international students could face deportation for working more than the set maximum, a regulation set by Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC).

Last May, Jobandeep Sandhu, an international student from Punjab, India, worked as a truck driver while going to school, until he was arrested for working beyond the limit. He is now facing deportation, according to CBC. Sandhu didn’t have a choice but to work additional hours, says Descalzi.

Amir says he had to work just over the 20-hour limit to ensure he didn’t have to go back to the rat-infested apartment.

“No one was ever strict on checking how many hours I have been working,” Amir says, but with the rise of international students, “the [CIC] are starting to check up more.”

Even at 40 hours every two weeks, international students would only make up to $560 on a bi-weekly basis, since on Oct. 23, 2018, Ford cancelled the planned $15 minimum wage increase by repealing portions of Bill 148, freezing minimum wage at $14 an hour. At the time, Ryerson politics professor Myer Siemiatycki says the repeal of the bill would be “disastrous”—particularly for immigrant and student populations. According to Siemiatycki, this “very low” minimum wage had not, over an extended period of time, kept up with the standard of living.

“Some places won’t hire you if you say you’re international,” Disi says. Some students opt to not tell their employers their situations from the start and wait until after they’re hired.

Some students, such as Disi, work “under the table”—meaning they are paid exlusively in cash. “Toronto is expensive and I was into things such as concerts,” he says. “For me to actually have fun and go out and everything, I needed to make more money.”

In this situation, students are left to live “on the straight and narrow,” Nyangweso says.

Samantha D’Alessandro*, a senior at an international U.S. high school in Mali, hopes to attend post-secondary school in Canada, but worries she might not be able to pull it off financially. Unable to work while she attends high school because of safety reasons due to the country’s political climate, and because students on study visas in Canada aren’t allowed to work more than 20 hours a week, D’Alessandro has to find alternatives to finance her schooling.

Her parents have offered to support her by paying parts of her tuition and rent, but she doesn’t want to burden her family with the high costs of international tuition in Ontario.

“It’s difficult to find a balance between everything. I’m trying to get a scholarship, I’m trying to figure out how I’m going to afford things,” says D’Alessandro. “Obviously I can’t travel to Canada, so I can’t visit residences, I can’t do school tours. I spend so much time researching things on the internet.”

Descalzi says these students experience a sense of instability. Besides needing to pay for unregulated tuition fees, Descalzi says not all international students can access their provincial health care plan, which varies from one province to another. It leaves their health in a precarious situation while not necessarily having adequate health resources at their respective universities or colleges.

For some international students in Canada, they must make the impossible decision between eating and affording their education.

Descalzi says this aspect of the post-secondary education system seems “predatory.”

In his second year of Ryerson’s mechanical engineering program in 2016, Amir failed 10 out of 12 courses and was put on academic probation. While his family was on the other side of the world, Amir felt he had no support. Eventually, he had an emotional breakdown and asked a doctor for help.

The doctor advised Amir to reach out to a counsellor, which he ignored initially—but then reached out a week later. “I was literally in tears.” Then, he says, the counsellor called an ambulance, and with them came police services.

Ryerson has a policy, like other universities, which mandates calling an ambulance when a student shows signs of being in a crisis or if they’re a harm to themselves (or others). In regards to Amir’s specific instance, Ryerson did not provide comment in time for publication.

Due to the historically violent relationship between Toronto police and marginalized communities, having the police called on you can be a triggering experience for racialized individuals and/or immigrants.

Because of this incident, Amir learned he couldn’t reach out for help as easily as other students could, simply because he is an international student. He opts to focus on solving issues on his own. “It is isolating,” Amir says.

The gap between international and domestic student experiences is only made worse when the wealthy stereotype is attached to students, who in reality might be struggling to make ends meet.

Photos of ordinary foods with designer fashion labels imprinted on them with captions like “what international students eat for breakfast.” A video—with 50,000 likes—of South Korean singer, Mijoo, catwalking on the red carpet captioned, “International students walking into their 8 a.m. lecture.” These tweets are one of many on social media that enforce the generalization that all international students are wealthy—wearing designer everything to classes where other students are wearing sweatpants.

But as recounted by Amir, D’Alessandro and others, this couldn’t be further from the truth.

According to the European Association for International Education, international students often face mental health issues and stresses that are unique to their situation.

Unlike most domestic students, those from foreign countries deal with language barriers which may hinder their education and access to employment. Other issues include culture shock, the inevitable stress of being in an unfamiliar environment, expectations from their families back home and adjusting to their new home or living space.

Exasperated financial burdens, racist politics and harmful stereotypes can hurt international students. As a dual citizen—Spanish and Vietnamese—D’Alessandro will most likely apply for her student visa as a Spanish citizen as opposed to applying as a Vietnamese citizen.

D’Alessandro’s unsure if she can even afford going to school in Canada, but she’s already thinking about what she would do if she got here. She plays every card she has, because that raises her chances of being able to go to university abroad. And amongst all variables, not getting in is something she also can’t afford.

*Names have been changed for anonymity.

With files from Funké Joseph.

UPDATE: This article has been updated to include a comment from Ryerson University.

Ibrahim Hosen Somrat

very nice post

Luis ricardo vargas

For Canada, theinternational students market is financially very important. It is a huge bussinees. In general is a huge advantage bring International Students that pay in addition super hight tuitions, a lot of money in housing, food, transportation,ect. Then, the students pay for their education and trainning and then some of their, years later start to work to the canadian economy and apport taxes, being very efficient. In addition, they settled here and create families. Is an incredoble deal.

But behind of that, are an enormus efforts, some time no visible. Isolation, depressions and anxiety are generally very heavy load. Addittionally financial problems for the students and their families, most of the time not rich families.