Unlike many American programs, earning a scholarship for U Sports athletes is about school as much as it’s about skill and talent

By Will Baldwin

Illustration by Jaime Strand

On two separate occasions, Ryerson men’s hockey alumni Daniel Poliziani’s team’s season ended on a Sunday, the day before a midterm. Instead of being able to focus solely on studying like most students, Poliziani was in the thick of a playoff run.

For post-secondary athletes, this isn’t a unique story—it’s something they’re used to. According to Poliziani though, these challenges athletes face are often misunderstood by the average student. Poliziani wants people to know the common stereotype that student athletes have it easy isn’t true.

“I wish there was a way for people to understand,” said Poliziani, who graduated in 2019. “The consensus is that we have our school paid for and we’re just walking through university or whatever. That’s not the case at all.”

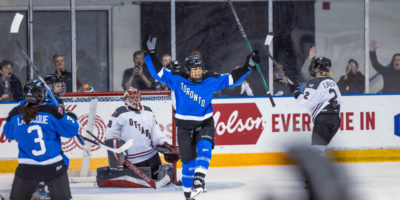

The life of a university athlete in Canada is very different from the glamorous image of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) experience in the United States. Across the NCAA, especially in high profile sports like football and basketball, athletes can get everything from tuition to books to even their housing paid for.

In Canada though, rather than the focus being solely on athletic skill as it often is down south, athletes must earn their scholarships in the classroom first. In U Sports—the governing body of Canadian university sports—there’s no such thing as a “full ride.”

Grades are taken extremely seriously in U Sports, especially at Ryerson. According to Taite Cleland, a member of the Rams women’s basketball team, it’s the first thing you have to take care of before you can even hope to play.

“In Canada [if] you don’t have the average, you’re not allowed to practice, you’re not allowed to play,” said Cleland.

Players across the country have to balance high educational standards in addition to the extreme amount of time they put into their sport. The time commitment is demanding, and without a guarantee of financial reward, student athletes often find themselves in a bind.

Rams women’s hockey player Avery Horlock has seen the good and bad effects of the scholarships given to Canadian athletes at play in her own locker room. For some, money is a motivator to do well in school. For others, financial help can be the only thing keeping them from having to move on from the sport they love.

“It means so much to the student who receives it,” said Horlock. “It can sometimes be the difference in what allows you to play hockey post-secondary, and that’s a huge deal.”

Two teams that face especially unique circumstances at Ryerson are the men’s and women’s soccer teams.

Kyle Stewart is a former captain of the Rams men’s soccer team who graduated in 2018. Although most athletes put in upward of 20 hours per week, Stewart estimated that Rams soccer players were forced to put in between 28 to 30 hours. This is due to the unique challenge that comes with the team’s facility being located at Downsview Park—around an hour from campus via transit.

Even with this extra challenge, Ryerson soccer players still have the same academic requirements as their fellow athletes at the school. During the season, Stewart and his teammates certainly felt the added pressure.

“It’s in the back of your mind,” said Stewart. “Once you get in the classroom it’s like, ‘Oh crap, I’ve got to do this to keep my GPA.’”

The only way a Ram qualifies for a scholarship from the school is if they maintain an average of 70 per cent or the equivalent grade point average of the school’s conference—the Ontario University Athletics’ (OUA)—rules. And, even if every Ram on each of the various varsity teams meets that average requirement, the conference has a cap which specifies schools are only allowed to reward 70 per cent of the roster.

According to Ryerson athletic director Louise Cowin, there are currently 100 athletes receiving financial support from the university across 11 varsity teams. In terms of the amount given out by the school, Ryerson’s hands are relatively tied by conference rules.

“The maximum award that a student athlete is eligible to receive under Ontario University Association rules is $4,500 per year,” said Cowin in an email to The Eyeopener. “The Department of Athletics and Recreation disburses $363,00 per year in athlete financial awards.”

Increasing the number of available scholarships starts at the national level with U Sports, not just the conference or even individual school level.

Last year, U Sports finished with a deficiency of revenue of $95,558. If athletes like the ones at Ryerson are going to see any change in their scholarship options directly from the school, it will take a massive growth in popularity and consumption nationwide of Canadian university sports.

One potential area for this growth is in Canadian mainstream media.

Just a month ago, CBC and U Sports announced they would partner on the coverage of the men’s and women’s basketball and hockey championships. This came after they covered the Vanier Cup, the Canadian university football national championship game in November.

It’s an important partnership for U Sports after the expiration of their deal with Sportsnet last season. For Chris Wilson, executive director of CBC Sports and Olympics, he sees lots of potential.

“I’ve always thought that the magic of U Sports is that, if it can pull itself together, it has 50 media outlets in sort of every nook and cranny in Canada,” said Wilson. “The real key will be, can us as the media partner, the conferences, the schools and U Sports all work together and realize the value is in the collective volume that tells stories from across the country.”

The reality for Canadian student athletes is that no major media entity in Canada has fully invested in U Sports. Until that happens, and the potential for revenue growth develops—therefore allowing for more financial rewards, the system is what it is.

That system forces athletes like Cleland to keep their priorities in order. For her, she understands that Rams are students first, and athletes second.

“Essentially, there’s more to life after university basketball,” said Cleland. “It’s the real world where your academics and education are going to pay forward.”

Poliziani, to his credit, has found a way to extend his hockey career by playing in France this season. He says that it’s important to consider how much extra effort he and his fellow Rams put in.

“We do get some scholarships but those aren’t handed to us, we work hard for those like anyone else would,” said Poliziani. “I think every single Ryerson athlete works so hard to earn an education and play 110 per cent on whatever court they’re playing in.”

Michael

I lived in Ontario for 36 years, but I didn’t know student athletes get scholarships. I thought the good High School athletes went to USA for the full ride. But it’s handled very different. Thanks for clearing that up. Prefer Canadian system