By Dream Homer

Lacrosse is seen by many Canadians as the national summer sport, but the game holds a much deeper cultural significance and pride for members of the Six Nations.

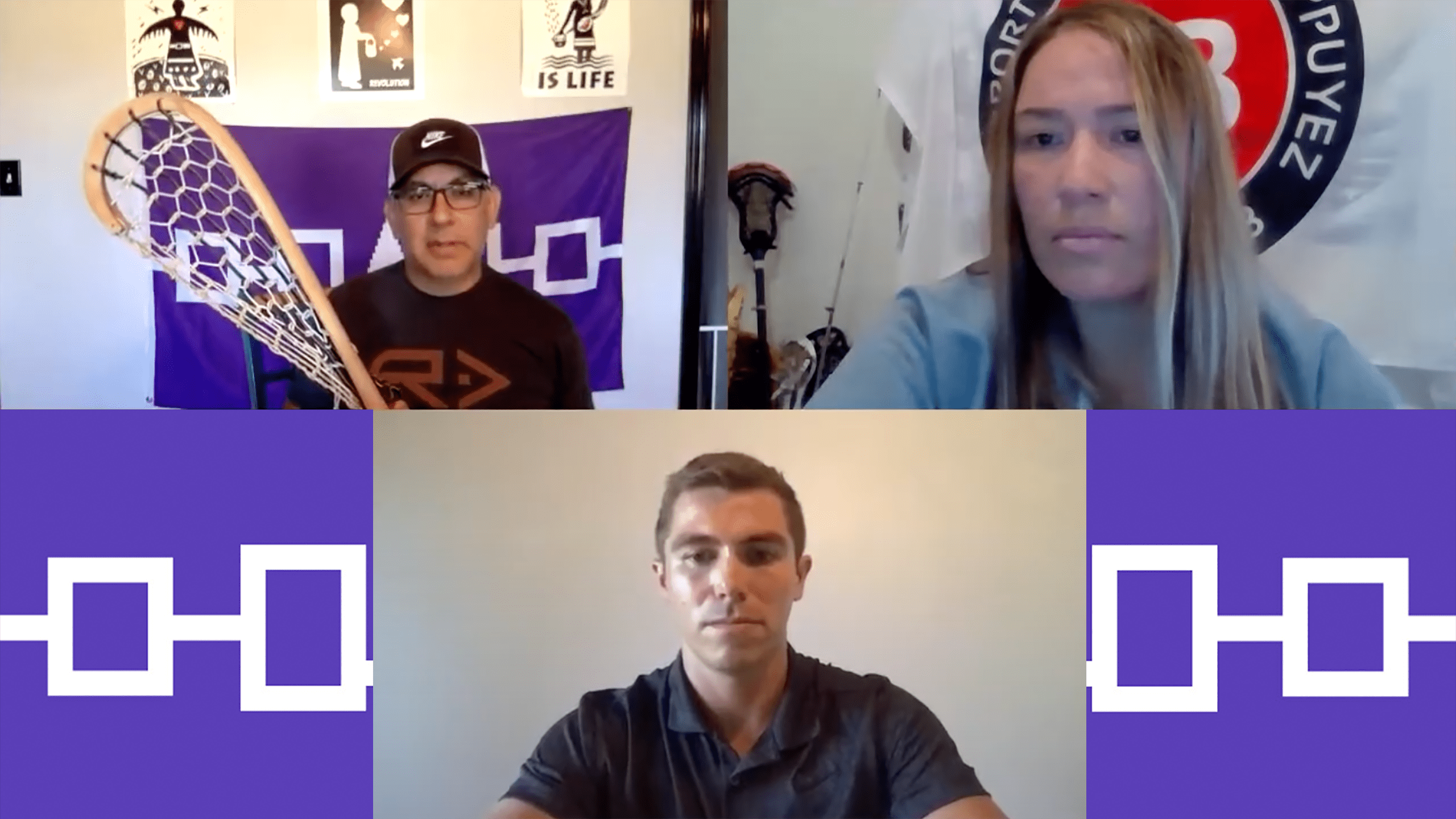

Professional Indigenous athletes Mekwan Tulpin, Keir Johnston and Dallas Squire went in depth on the historical and cultural significance of the game for Ryerson’s 2020 Pow Wow Education Week, which was held virtually this year.

“Regardless of what sport you play, everyone should know the historical significance of that sport,” said Squire. The same holds true for lacrosse, “the fastest game on two feet,” as Squire describes.

Originally known as “stickball” or “Tewaaraton,” the Mohawk name for the game of lacrosse is more than an amusement for Indigenous peoples in Canada. For them, it stems all the way back to the story of creation. The game has always been played to express gratitude and provide enjoyment for the Creator, according to the Onondaga Nation.

The game involves using a hooded stick to carry, pass, catch and shoot a ball into opposing nets on a grass field. Like soccer, it’s fast-paced and exceptionally physical. Its word in the Onondaga language is “baaga’adowe,” which means “bumping hips.”

The game of lacrosse has played an important role in sharpening ancient Indigenous hunting and gathering skills, which were part of the physical demands of their everyday life.

Lacrosse is also connected to spiritual wellness and healing. Each member would have their traditional sticks and play a game in honour of those who were sick or needed a dose of good medicine. It’s also considered a means for recreation and enjoyment.

“There’s a source of pride that comes along with playing lacrosse,” said Squire. When babies are born, it’s tradition for several Indigenous cultures to gift them a lacrosse stick. Learning the skills involved were picked up almost naturally while living in traditional Indigenous society.

The equipment and spiritual meaning

The lacrosse stick acts as a conduit for the spiritual elements of the game. Each First Nation has their own tradition and version of the stick used.

The significance is that the stick was a living entity standing before a tall tree. “When you hold a traditional stick in your hand, you’re embodying three spirits: the wood which came from a living tree, the leather in the pocket of the stick that embodies an animal and yourself,” said Squire. “You have a spirit as well.”

In the past, lacrosse was typically played with a wooden stick but eventually transitioned to plastic and fibre glass.

The embodiment of the three spirits is where the “good medicine” originates from. Every time a stick is made, there is an honouring of that process which was certainly timely, but precious. Squire said that when his grandfather made wooden sticks, the process would take up to a year. Much of it involved honouring the hickory tree which provides the material for the stick—from drying out the wood to eventually bending it into the desired shape. Deerskin was mostly used for the pocket of the stick and the game ball made of animal hide.

“We believe everything has a spirit and so we are honouring that tree for giving us the opportunity to make this lacrosse stick so we can play this game that we [have] played since the time of creation,” said Squire.

Lacrosse brings communities of Indigenous folks together. Squire detailed his early memories of playing the game with his family and friends from other communities, who were close and tight-knit from birth.

Squire mentioned how playing lacrosse was an outlet of good energy. There was never pressure to play lacrosse for Squire as a young kid, however he explained how he naturally “gravitated towards it” and felt honour being a part of something so spiritual and cultural.

Lacrosse has adapted widely throughout Western culture and continues to grow in universities and colleges across North America. Unfortunately, Ryerson is not among the post-secondary schools that have a lacrosse team.

“All of our competitive clubs are student-driven, and if a group could demonstrate that there is enough student interest to build a sustainable program, we would certainly be willing to work with them on it,” said Ryerson’s competitive clubs director, Ryan Danziger.

For the Indigenous community, lacrosse is sacred and descends from an important part of their history.

“The feeling you get, the freedom. I think it’s a lot about freedom when you’re playing this game,” Squire explained. “It speaks to a very primitive bones in our body that you’re free.”

Leave a Reply