Words by Stephanie Beattie

Visuals by Vanessa Kauk and Oceanne Li

Surrounded by the hum of coffee shop chatter, Brennan Seedhouse Robinson sits at a circular table in Toronto’s east end. The table, hardly large enough to fit a laptop, is the meeting spot for the designer and his friend. While he works primarily in design, something about a human-filled atmosphere above painted tile floors allows his creative ideas to flow.

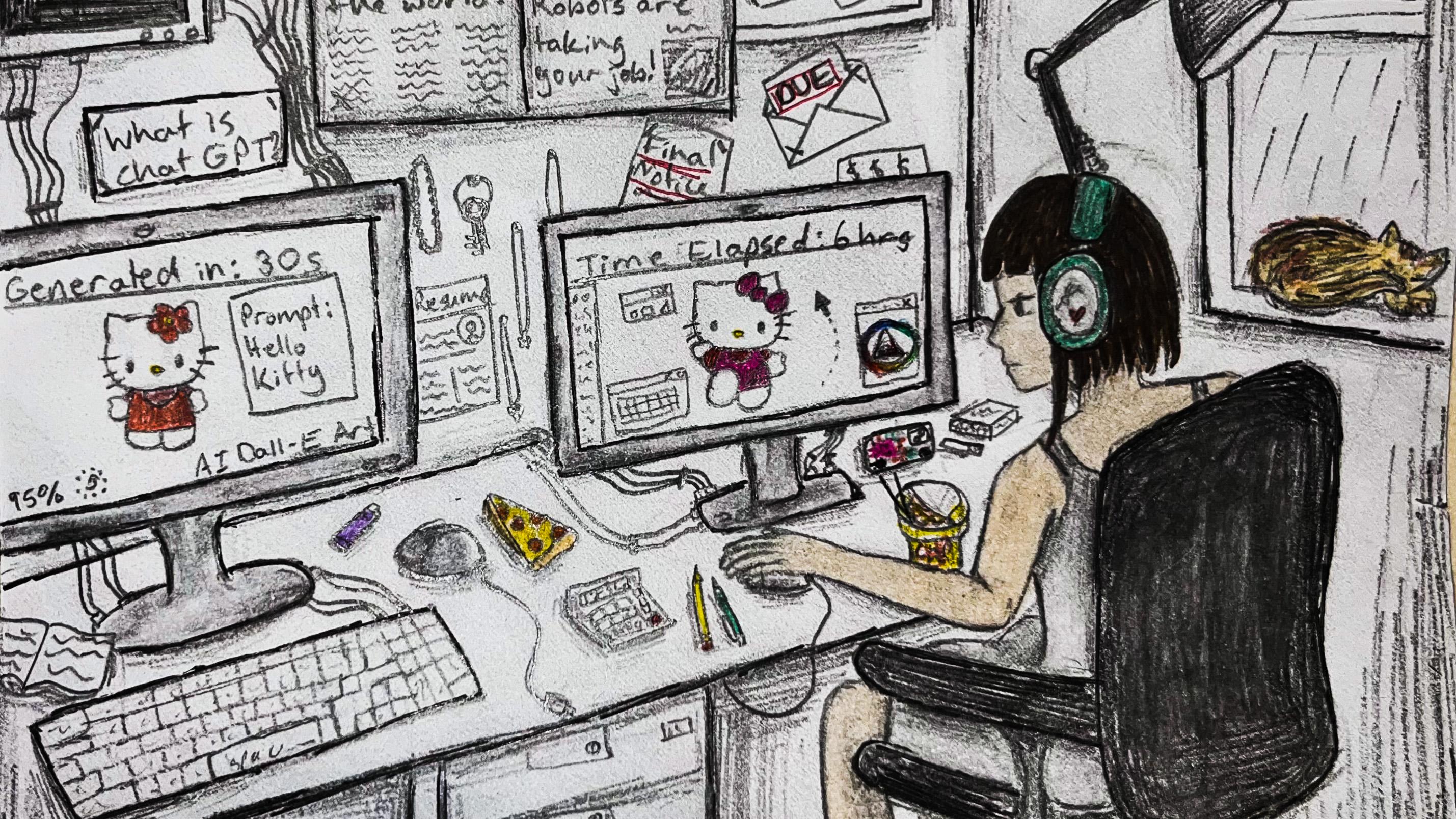

It was in this warm coffee shop, during the end of January, where Seedhouse Robinson and his friend got into a conversation about downloading Midjourney, an artificial intelligence (AI) art generator that runs through a channel on the social messaging and computing platform, Discord.

The Midjourney server currently holds the largest number of members on Discord with about 9.5 million users, according to a January 2023 Statista article. The technology is one of many AI engines that generates art by scanning the web for past images and information based on written prompts.

Seedhouse Robinson began experimenting with prompts. “I got really fascinated on how I could push the bounds within my own work.”

Although he was intrigued by the concepts AI could combine visually, none of Seedhouse Robinson’s creations ever went further than the downloads folder on his laptop. As a fourth-year media production student at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU), he wanted to see if AI technology could advance his productivity as a designer and generate images “purely from a non-commercial perspective.” For him, using the AI art generator was like an addition to his usual sketchbook process.

“That fascinates me, not in the actual creation of that image but what sort of concepts it might pull together, more as a brainstorming tool,” he says.

However, he’s not fully sure how comfortable he feels using AI generators like these. “I am quite cautious of the ethical implications of [AI art], being so related to my field and even hearing of colleagues and friends who have been impacted by this,” he says.

When he combined prompts with the names of famous painters, the program would mimic their art style. For the average person, famous paintings can be recognizable. But for smaller and current artists, Seedhouse Robinson questions how issues of copyright and ownership will impact their work.

“There’s a lot of reference work to pull from for a program like that but it was still an interesting insight to what it could be for a lot more current artists,” he says.

AI-generated art hit a new peak in popularity at the tail end of 2022. The website NightCafe Studio, for example, is a popular modern software that uses text-to-image technology to curate images within seconds. Users generated over 35 million artworks as of October 2022, according to their website. And in December 2022, on social media platforms such as TikTok and Instagram, many people used AI filters to generate surreal style scenes and transform their selfies into animated portraits.

And while some TMU students specializing in design may be intrigued by AI—from the realistic TikTok filters to surreal art production—they are coming to terms with the role the technology might play in their chosen industries. As AI becomes more popular, students say they are balancing the good it can bring to their fields with its real ethical concerns.

AI technology scans existing images and rapidly combs through online information, which could include other people’s published art. This quick and efficient trend not only pulls from other artists’ work without attribution but there are also foundational concerns surrounding implicit bias in the technology. Still, AI’s popularity is growing rapidly and could make its way into more creative fields in the future such as digital and fine art spaces.

Debashis Sinha, an assistant professor at TMU’s School of Performance, began working with AI technology, specifically with sound and media, in 2019. Recently, he says he’s noticed there’s been a lot more concern about the ethics of AI, especially in the art scene.

“When we talk about the assumptions of AI in the creative space, I think a big [worry] is the repurposing of previous work and the use of these massive data sets, that have been compiled without permission or without consent,” he says. Data sets can include various images, text, audio, videos and numerical data, according to DataToBiz, a data analytic and AI consulting service.

Some people on social media are also concerned about AI taking up space in cultural production. An AI-generated art piece, titled “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial,” by game designer Jason Allen, sparked controversy online when it won first prize in the digital arts category of the Colorado State Fair on Aug. 26, 2022. After the precedent-setting win, Reddit users debated whether AI art is taking away opportunities from other traditionally more hands-on artwork.

Some comments demonstrated concern about the potential disconnect between the artist and the medium. Since AI artwork is visually produced by these online generators, it’s unclear who should be given credit—the person who writes the prompt or the technology itself.

Seedhouse Robinson says he’s interested to see if AI adapts to future potential policies surrounding ownership and copyright.

“It’s having a huge impact, especially for designers and artists. It’s quite terrifying.”

As he tries to navigate how AI might play into the creative industries, Seedhouse Robinson says it has the potential to do good but better governance in terms of attribution would give him “a lot more confidence” as a designer.

Slouched in a patchwork-covered spinning chair, Julia Dumont scrounged through her iPad for information as she researched fashion history from the ‘80s. After being inspired by the costume designs in the popular television series “Stranger Things,” Dumont, a third-year fashion student, started a passion project in the comfort of her family cottage near Lake Huron. It was a clear summer day in August 2022 and instead of swimming, Dumont decided to stay indoors reading and conducting research for about four hours straight for the sole purpose of engaging with fashion history.

But before she knew it, she had reached a halt.

“It got to the point where I had so many tabs open in Chrome that it stopped counting. And it just gave me a little sideways smiley face telling me ‘You’ve gone too far,’” Dumont said. The smiley face appears once a user reaches over 100 tabs on a Chrome browser. Most of the tabs Dumont had open were collections of subcultures and niche pockets of fashion history but she didn’t realize how many tabs she actually had open until the smiley face appeared.

Unlike the heavy research conducted by Dumont, she says she’s seen some designers and people interested in fashion talk about AI generators as a means of “really fast ideation.” According to the Interaction Design Foundation, ideation is the part of the creative process which includes generating ideas for a design. Dumont says it’s important to cite your sources and not “rip anyone off.” She adds that since AI combines past images without attribution, using it in the ideation process would make it “significantly harder to map where the inspiration is coming from.”

When it comes to her own creative process, Dumont has tried Artbreeder, a machine-learning-based art website, to generate different faces for her sketches. Although she used the software with the goal of beating “same face syndrome” (which is when an artist unintentionally draws similar facial features on multiple characters), the AI-generated faces that came up on Dumont’s screen all looked the same as well. She discovered that when a user tries to prompt AI to generate anything beyond traditional Eurocentric beauty standards “you get this weird, garbled nonsense,” with unrealistic and out-of-proportion facial features.

Norah Lorway, an assistant professor at TMU’s RTA School of Media with a PhD in computer music and human-computer interaction, works with AI in sound, computer science and digital healthcare.

“It’s perceiving, synthesizing and inferring information and this is all determined by machines,” says Lorway. This machine learning is “like a spreadsheet,” they added. While it’s helpful to categorize and sort data, AI lacks the multifaceted emotional qualities of the human spectrum.

“Any kind of emotional quality that is programmed to these algorithms, I think, is going to be biased toward the person who made it.”

Lorway says a lot of algorithms are created by “cis[gender] white male programmers,” allowing racial and gender-based biases to go unchecked. “There’s not a lot of responsibility and [accountability] for it,” they added.

There are organizations today that are fighting for better inclusivity in the AI sphere. The Algorithmic Justice League (AJL), founded by computer scientist Joy Buolamwini, is a non-profit organization based in the U.S. that combines art and research to raise awareness toward the harms of AI technology. According to the organization’s website, Buolamwini calls algorithmic bias “the coded gaze,” where racism, sexism, ableism and other forms of discrimination are embedded within AI systems.

The AJL was created from Buolamwini’s 2017 thesis project at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology called “Gender Shades.” In the video on the Gender Shades website, she says her idea for the project was born when she saw how multiple facial recognition softwares only detected the faces of her friends with lighter complexions. It wasn’t until Buolamwini, who is Black, put on a white mask that completely covered her face, that the algorithms recognized her. A deeper dive into the technology revealed common issues of misgendering and other inaccuracies, which the AJL continues to explore today.

“Most people don’t question [bias] because it’s just a part of everyday life and that’s a problem,” says Lorway. “So, I think this new Justice League is trying to question it and I think it applies in the arts as well, for sure.”

Alongside issues of bias within AI, Dumont also noticed a lot of repetition in machine-generated art. “AI loves butterflies, for whatever reason, when they’re generating gowns,” she says, adding that some softwares often generate the same bodice and a skirt that rarely changes.

This semester, Dumont has an assignment to create a completely original concept for a design. She was given specific instructions not to draw inspiration from other artists or pieces of fashion. “It’s very much the opposite of AI. It has to be original, it has to be specific, non-vague and not using any copyrighted materials,” Dumont says.

Given her love for historical research, Dumont decided to compile ideas for a design based on a raven, a bird known for its dark colour and symbolic meaning. Her process began by combining research on the mythology, pop culture and science behind the animal itself.

For Dumont, working on this project has demonstrated how human thought and ideation differ from AI—the latter isn’t trained to think about the more tactical aspects like how a design feels or sounds in real life. For instance, her idea of layered garments made of satin and tulle would produce a soft sound like rustling bird feathers as the outfit moved, which Dumont says would not be typically thought of by a machine pulling from past images.

She hopes to put this concept together physically someday, which will require even more research on how fabrics drape and feel, the cost and the sustainability of each material.

Part of the creative process, Dumont says, is taking materials and figuring out how they can be made into something. “AI might just kind of ignore how the physics of certain materials work, making it harder to translate,” she adds.

It’s not uncommon for Ashan Mahendran, a fifth-year graphic communications management student at TMU, to spend hours on Adobe Creative Suite perfecting his latest projects. Inspired by pop culture, Mahendran usually creates mixed media images in Photoshop for leisure. He says while AI makes the design process faster, it doesn’t necessarily lead to the best final outcome for the artist and the artwork.

“It’s best if we just use our own skills to make our pieces and everything. Using AI just cuts our work.”

As he keeps up-to-date with AI art discourse on social media, a piece that stood out to him recently was American rapper Lil Yachty’s Let’s Start Here album cover art, which was AI-generated. The album, released this January, featured a cover of seven people dressed in formal business clothing with digitally distorted faces.

Although the facial distortion on the album cover was likely intentional, AI art can sometimes produce unwanted errors. Mahendran says he once saw AI-generated art with seven fingers on a human hand, all of which looked the same in size and shape.

Despite AI’s technological flaws, Mahendran says he is seeing it slowly being implemented into the workplace and predicts that it’ll evolve more within the next few years. As someone who hopes to start working in the graphic design field upon his graduation this June, this is a cause of concern for him.

“I worry about it and it takes away the privilege to create art,” he says.

While some argue that AI will never completely replace human creativity, a 2016 study from the University of Oxford, found that approximately 47 per cent of U.S. jobs at that time were at high risk of being absorbed by AI machines.

Not everyone is all that concerned though. For instance, while Sinha believes that it’s important to acknowledge the reality of AI in today’s world, he also thinks these tools won’t be taking over all cultural production.

“It’s just simply not in the cards. It’s not going to happen,” he says. Sinha says AI generators should be considered as “statistical modeling tools” because they function by pulling from the past. In music and performance, AI algorithms draw from previous musical data to help create new sounds and images.

However, regardless of how advanced AI technology gets, Sinha says there will always be space for us to tell new stories.

“AI and machine learning in these processes will never answer the questions that we, as human beings, ask of ourselves, ask of our creativity, ask of the world.”

A common day for Seedhouse Robinson consists of him sitting by his bed alongside plants that have unexpectedly reached his height as he opens his Adobe programs and refers to notes and sketches. His recent desire to work with his art in a more tangible way has fuelled his decision to purchase a new scanner. This new device allows him to print his clean, minimalist designs and turn them into something he can physically hold in his hands. There is, however, the occasional misprint.

“I think those little bits, even if it’s just the distortion of a scan, that is one thing I absolutely adore and want to see more of in my work,” he says. “It’s those little imperfections that make something feel so much more real in a digital space.”

Like all technology, Seedhouse Robinson also saw imperfections in AI-generated images. When prompts were combined with famous artist styles on Midjourney, he said one portrait image generated more than two hands. Despite the occasional human inaccuracy, Seedhouse Robinson says he’s excited about embracing those machine errors in the future of AI because those errors are a reminder that human-made art is still essential.

“The worse job it does of replicating other artists’ work, the better.”

While AI can provide some inspiration for artists to continue their work, nothing beats genuine human connection for Seedhouse Robinson. He says when a “creative block” hits, he often visits a local cafe or park to connect with the community around him. These seemingly mundane interactions allow artists to create art that is personal and unique to the human experience—which is something that AI cannot replicate.

“As of yet, in my own experience, I have not seen a machine reproduce something that gives that same sense of connection, that same sense of community around the world.”

Leave a Reply