By Allan Woods

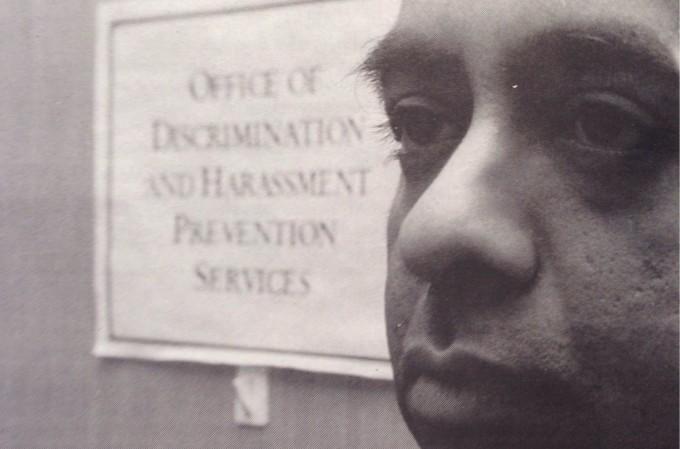

Each time the bell above the doorway sounds, Sri Pathmanathan’s head of thinning black hair pops over his desk in the Ryerson discrimination and harassment department’s second-floor office. His heavy lids cover eyes that look ahead and just off to the right in the general direction of the hallway.

“Hello?” his unsure voice asks as he looks out of the side of his eyes for bright colours and distinct shapes. “Can I help you?”

Behind the desk are the tools 34-year old Pathmanathan relies on: a computer with voice-recognition software, a 19-year-old braille machine that types an alphabet of dots and allows him to read with his fingers, and a white cane that, for now, is tucked away on his desk between a printer and scanner.

With these tools, and his drive to succeed, Pathmanathan has blighted his blindness.

Sri Pathmanathan was seven when he first noticed that something was wrong. It began when, as a young boy in Jaffna, Sri Lanka, he started having trouble reading. The night blindness slowly shut out whatever light remained in the twilight of the city, located at the northern tip of the country.

“I was confused and I couldn’t communicate,” he remembers. “I didn’t know what was going on.”

His parents, both Hindus, first denied what was happening to their revered eldest son. Then they began to blame themselves, believing his affliction was the result of their bad karma — something they had done wrong in a former life.

“They were kind of feeling guilt and shame. It’s not their fault, but because of the stigma and status problems, they blamed themselves.”

He remembers the special attention he was given as a young boy. In class, he was pushed up to the front row so he could see what was clear to everyone else from much farther away. In denial, his parents suggested that he was not actually losing his sight but rather had a reading problem. The isolation gave way to a religious devotion rare in young boys. When he was eight years old, Pathmanathan became a vegetarian, the only one in his family.

Then came denial. By the time he had reached 16 years of age, his vision had so degenerated that he relied on a cane to tap his way through the world. But he learned how to ride a bicycle so he could go play in the side street near his house like his younger brother and sister. Then he taught himself to drive a car and a motorcycle. He rode back and forth in that side street until he narrowly missed hitting a good friend’s mother, reminding Pathmanathan that he was not like other people, that he was blind.

“Because of my childhood experience, I always had a quest to meet other blind people with whom I could meet and speak freely,” he says.

Pathmanathan would skip school to spend his days at the local blind association, with others who understood his situation and shared his outlook. Then, a school tutor introduced him to a friend, Ravi, who had been blind since birth. The two became fast friends, Pathmanathan remembers. “I always had a smile on my face. It gave me a lot of confidence.”

They talked about everything that normal teenagers talk about from school to girls to mutual friends. They were also able to talk about their blindness and offer each other the support they were unable to find in society.

But Pathmanathan’s parents, still uncomfortable with the idea that their son was different from others, were not so accepting of the friendship. When he brought Ravi home to meet his parents, the two boys sat on the family couch while his parents remained standing, making an innocent situation incredibly awkward. Though their son had made peace with his blindness, they dwelled in a darkness, unable to deal with the guilt that, somehow, this was their fault.

In 1983, Sri Lanka broke out in civil war. “The military began picking up teens and young adults who were in the streets,” Pathmanathan remembers. “My mother got scared and asked me to stay home because I couldn’t see where the military was. She got really worried about my safety.”

Worried also for his future, which they saw as severely limited by his blindness, his parents urged him to leave school and open a store. They even offered to buy it for him, but he refused.

“No, I have to go to school,” he explained. “that is the only weapon I have.”

Three years later, the family moved to India where Pathmanathan enrolled at a university in Madras and completed a bachelor’s degree. Then he moved away from his family — a 36-hour train ride away — to attend university in New Delhi, at the country’s northern tip.

There was tremendous support from the community, he says, but even here, at a university run by Jesuit priests, he came up against those who told him what he could not do because of his blindness.

He went to school with the intention of studying economics but was told there are too many visual learning tools, such as graphs and maps, involved in the subject. Instead, he chose sociology.

Pathmanathan graduated the program with honours and secured himself a scholarship to the London School of Economics in England.

“I always felt that, because of my disabilities, I had to work longer, work harder,” he says. Entering his second masters degree, his success in school was already evident. But it came at the expense of his religion. “I was studying, studying, studying all the time. I drifted from religion,” he says, adding that it was then that he started eating meat again.

After finishing a masters degree in social policy at LSE, Pathmanathan moved to Toronto in 1992.

“I took it as a challenge,” he says. “I’d survived in India and in London. I knew I could survive in Toronto.” And he says his background working in the community services field gave him confidence that he’s be able to find the support to help him adjust to life in a new country.

Now, Pathmanathan tenderly taps his way on to campus each morning. He holds one arm protectively over his one-year-old son, Ajeyram, who stays at the campus daycare. In his head, he holds a map of the school. He knows detailed directions — long series’ of lefts and rights — that allow him to negotiate his way around campus. And he knows the crowded spots to avoid, places where his cane doesn’t give him clearance.

He first wandered on to Ryerson’s campus for the board meeting of a local non-profit organization that familiarizes the blind to their surroundings. He returned to the university in 1997 when he joined a research team that studied the discrimination faced by immigrants with disabilities as they settles in Toronto.

It wasn’t until 1999 that he found his niche, back at Ryerson, working in the office of discrimination and harassment. He works the reception desk organizing files, which he marks with braille lettering, organizing books, videotapes and news clippings, scheduling appointments and greeting students in need of help.

“I’d be lost without him,” says Ryerson’s educational equity advisor Tony Conte, who is new to the school. “He’s taught me more about this campus and showed me more things [than anyone else].”

Conte says people often assume that, because he is sighted, he’s leading Pathmanathan somewhere on campus. In reality, he says, it’s the other way around. “Usually, whenever I’m with Sri, it’s because he’s taking me somewhere.”

And Pathmanathan’s parents, who feared their son would have to face a darkness in his life, now realize the strength which has allowed him to succeed. “[Now] I think they feel proud,” he says.

“Most people think [being blind] is difficult but even good people fall victim to natural things.”

Leave a Reply