By Maggie Macintosh

What do the Ramettes, Ryettes, Ewes and Lady Rams have in common? If you ask Carly Clarke, head coach of the women’s basketball team at Ryerson University, she’d say what you’re probably thinking: these names don’t exactly stand out as being fierce sports teams.

“They don’t spark the competitive fierceness that I hope our team represents when we play on the court, that’s for sure,” she says.

Today, the women’s basketball team—like all athletic teams at Ryerson—plays with Rams jerseys in blue, white and gold. But that wasn’t always the case. While men’s varsity teams have always played as the Rams—aggressive animals with horns—since the first teams started competing in 1948, women’s teams have been given less intimidating names.

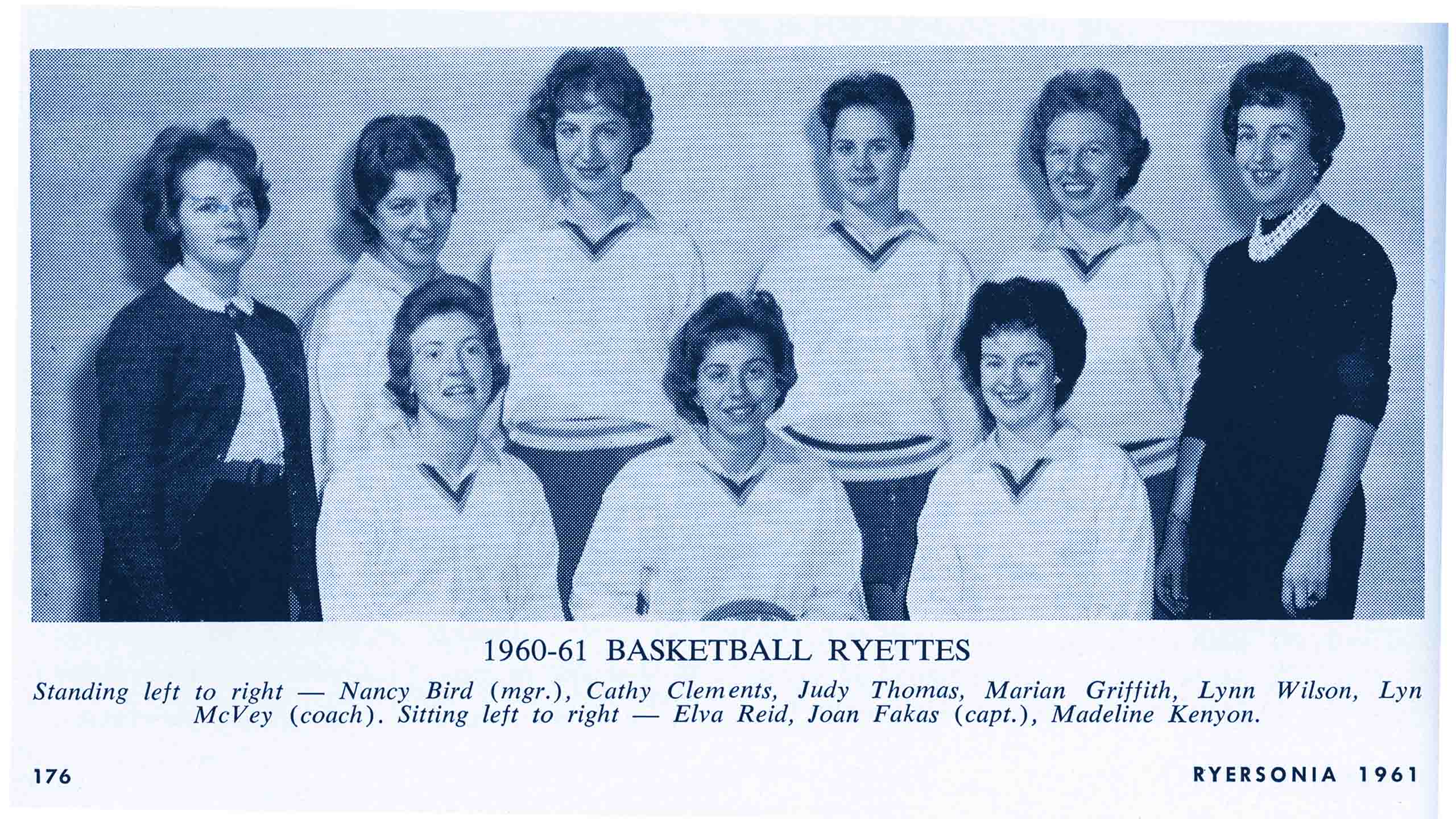

Ryerson’s first women’s basketball team was called the Ryettes in the early ‘50s. The Ramettes, a second basketball team, made an appearance in 1954.

“Our team makes jokes about those names every once in a while,” says Kryshanda Green, a forward on the women’s hockey team.

When Green’s teammate Laura Ball hears the old names, she thinks of something dainty and innocent.

“If I were coming into a game against a team named the Ramettes and we were named the Buffalos, I would probably laugh,” she says. “I would think, ‘What even is a ‘Ramette?’”

A page in the 1961 Ryersonian yearbook dedicated to female sports states that “girls’” organized sports at Ryerson somewhat disappeared between 1958 to 1961 due to diminishing facilities. This meant “a return to old-fashioned parlor games such as elbow-bending and boy-chasing.”

What does that even mean?

It gets worse: “In eight games,” the yearbook continues, “the girls failed to win for coach Lyn McVey, but the comforting attention of the male Rams on the long bus rides home more than compensated for any humiliation.”

And later that year, “the girls’ gym was converted to an intimate bistro, known as the Cloud Room.”

These names don’t exactly stand out as being fierce sports teams

The Ramettes and Ryettes were both eventually phased out a decade later, when the women’s basketball and volleyball teams started playing as the Ewes in the early 1970s.

Ewes are female sheep and, according to online sheep-raising guide Sheep 101, are generally docile and non-aggressive. Rams—male bighorn sheep—are described as being “very aggressive,” especially during mating season.

The Ewes practiced three nights a week for two hours in one third of the gym, while the Rams basketball team practiced five nights a week in the other two thirds, according to a worn-out clipping from a 1978 edition of The Eye, in the Ryerson archives. “The Ewes basketball team charges that they do not get enough full gym time to practice properly,” the article reads.

The Ewes were later replaced by the Lady Rams, who competed until 1994, when athletics made all teams play under the male animal mascot. Around this time, Ryerson was granted full university status.

“The culture has changed a lot in how women are viewed and how women’s sports are viewed,” says Clarke. “It’s good that athletic teams are adapting.”

Green, who’s in her second year in Ryerson’s politics and governance program, says people have been conditioned into thinking women are weaker, so there’s a perception that their level of sport competition is weak. “But they’re wrong,” she adds.

One of the biggest historical perceptions is that sports involve manly or male characteristics versus “lady-like” stereotypes, according to Clarke.

“It’s OK to be tough and strong and physically fit and powerful as a female athlete,” she says. “And I think, perhaps, taking us back to the mascot conversation, hopefully that’s one of the reasons Ryerson went away from those softer mascot names.”

The standard for university teams in 2018 is to play under one mascot: University of Calgary Dinos, University of Winnipeg Wesmen, Dalhousie University Tigers, and so on. Still, there are exceptions: University of Alberta athletics are split into the male Golden Bears and female Pandas.

“I know the University of Alberta has a history with the Pandas and are very proud to be Pandas, so it’d be interesting just to know what their perspective is,” says Clarke. “I’m certainly proud to play under one name here.”

Connor Hood, a sports information and communications officer at U of A, says the names come down to tradition. The men’s and women’s teams used to be separate departments, and when they merged, the university stuck with the historical names.

“We still have to continue to fight for popularity and equal footing in the grand scheme of things”

For McGill University, the men’s teams are the Redmen, a name that evolved out of male athletes wearing red jerseys. The women’s teams, the Martlets, are named after the cheery red birds found on the university’s coat of arms.

And then there’s Laurentian University, in Sudbury, Ont., home of the Voyageurs. Men play as the Vees, while the women’s teams are known as the Lady Vees.

“I already feel like, at times, women’s teams can get less campus attention and school spirit solely based on being a female sport, so if there was a difference in mascots there is definitely no way [people] would take us seriously,” says Ball, a second-year student in Ryerson’s sport media program.

A 2016 report on female sport participation produced by the Canadian Association for the Advancement of Women and Sport and Physical Activity found women’s sports only made up four per cent of sports coverage on Canada’s primary national sport networks in 2014.

Just this month, Ryerson basketball alum Kellie Ring tweeted about the Carleton University men’s team getting more press coverage than the women’s team, even though the men had lost in the national semifinals and the women won the tournament.

Still, Ring, who played for Ryerson in 2017, says women are starting to get more coverage and recognition. “Sometimes, however, it’s not the right coverage,” she says.

She wrote her digital media master’s research paper on self-representation strategies of male and female pro tennis players and found female athletes are more likely to portray themselves in non-athletic contexts. This reflects traditional media practices, she says.

“Even though female athletes kick ass on court or whatever they play, the reporters, newspapers, media, etc. portray them as mothers, or females first, athletes second,” she says. “With social media, female athletes have the opportunity to change people’s thoughts about women’s sports.”

Clarke agrees both viewership and popularity are struggles for female athletes, adding that more people watched the women’s U Sports basketball championship game this year than the men’s, “which is exciting and maybe an indication that there is a fan base for women’s sports.”

Despite their roots as the Ramettes, Ryettes, Ewes and Lady Rams, women’s teams at Ryerson are now treated pretty equally, something Clarke says allows men’s and women’s teams to succeed and makes her proud to be part of “the Ramily.”

“But, in saying all that, we still have to continue to fight for popularity and equal footing in the grand scheme of things,” she says. “I don’t want to downplay how women have to continue to fight, particularly in sport, for respect.”

Glenn Arthur Pierce

The takeaway from this article is that Ryerson’s women are now “treated pretty equally” for having adopted the “Rams” name (which only applies to male sheep). That’s an interesting take … that sexist language can be readily addressed through the adoption of a masculine-by-preference linguistics model.

Glenn Arthur Pierce, author of Naming Rites: A Biographical History of North American Team Names