By Sara Noori

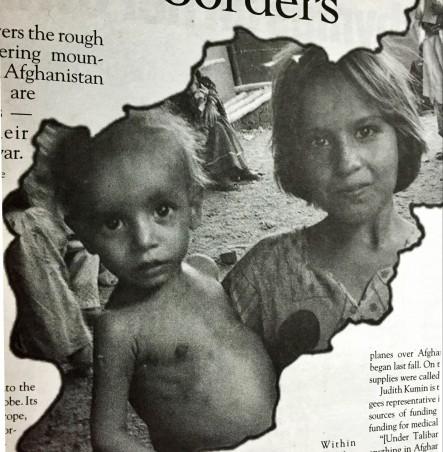

A valley of tents covers the rough terrain between towering mountains. This is Northern Afghanistan and inside the tents are thousands of refugees — displaced from their homes by decades of war.

But they’re not alone, inside those roughshod tents. When the whole world stands still and other international aid organizations abandon the crisis area due to danger, the men and women of Médecins San Frontères move in.

Médecins San Frontères (MSF), also known as Doctors Without Borders, is an international medical aid organization with a commitment to protest against human rights violations.

MSF’s concept is a noble one. At a moment’s notice, the members of the volunteer-based organization troops into the hundreds of trouble spots around the globe. Its volunteers have worked in Africa, Europe, Asia and South America since the orgainization’s inception in 1971. Essentially an international clean-up crew and triage unit, MSF provides much-needed lifelines to areas ravaged by war, disease and famine, efforts that earned the group international acclaim and a Nobel Prize for Peace in 1999. Beyond the medical support provided by the make-shift hospitals and clinics, they also work to reconstruct ravaged countrysides by rebuilding the damage of battle. Demolished schools are rebuilt, fresh water wells are dug and a community starts to heal. And right now, Afghanistan needs MSF to heal its own deep scars left by war.

MSF workers provide not only medical assistance but also food and clean water. They also dig latrines and set up first aid stations and field hospitals. And nurses are just as important as doctors. While doctors eamine patients, nurses do most of the actual hands-on medical work.

Logisticians, administrators, plumbers, radio operators, lawyers, mechanics and accountants also make sure that essential medicine, food, fuel, people, vehicles, fresh water and tools are delivered to those at the centre of the emergency. It’s all about working within the community with the constant goal of rebuilding what is usually a broken and battered population.

“Our programs include blanket feeding that target children five years and under. But some of the aspects of our program also focus on women where there is a very little access to health care. We do provide urgent medical care to the community, communities that are in need,” says Michèle Joanisse, director of fundraising for MSF Canada.

Médecins San Frontères was formed in Paris by a group of French doctors and journalists who had just returned from a Red Cross mission in Biafra, Nigeria. After witnessing the horror of the Biafrian war in the early 1970s, they were determined to establish an organization that was politically economically and religiously independent from the country they were working in, but would also provide rapid medical aid at the same time.

Within the organization, formalities such as calling someone by their title don’t exist. Everyone is equal and on a first name basis. Volunteers get their flight and basic living expenses paid. They often have to endure primitive conditions for months, depending upon the need of the region.

Canada’s chapter of MSF was founded in 1991 and has since sent hundreds of Canadians across the world; among them is Leslie Shanks.

The 36-year-old Shanks is remarkably down to earth. Dressed down in casual cargo pants and with her hair wound into a bun, she looks more like a regular university student than what she is — the president of MSF in Canada. Shanks has been involved with MSF for several years. Though she has never been to Afghanistan, she has done years of work in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a country torn apart by civil war.

“We have extensively worked in Afghanistan since 1980 and feel an urgent concern about the current situations,” says Shanks. “Because of the Taliban, we had to pull our international staff out of Afghanistan.”

Shanks says even though people are more aware of the Afghan refugee plight, it has been going on for decades. More than 12 million people have been affected by the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and all the internal conflicts since. Four million refugees are malnourished and more than one million currently face starvation. The Afghan refugee population is one of the largest in the world.

The Taliban were never on good terms with MSF. In 1998, MSF teams were expelled from Kabul, the once-cosmopolitan Afghan capital, but continued to work in poor rural areas close to Kabul such as Dashte Barchi and Khair Khana.

The Taliban made it extremely difficult for MSF to operate in Afghanistan. Convoys were blocked and foreign workers weren’t tolerated under their rule.

“But even though we [had] removed all the international staff or foreign staff, they still [continued] MSF’s program along the borders of Afghanistan,” says Joanisse.

On November 13, 2001, the Taliban left Kabul. The following day, MSF was right back in the city.

In Afghanistan, not only the medical expertise of MSF is important. The other component of the organization, the commitment to protest against human rights violations, is often loudly heard by their targets. Apart from protesting against the practices of the Taliban, MSF also took issue with the so-called humanitarian aid that was dropped by U.S. and British planes over Afghanistan when the bombing campaign began last fall. On their official website, www.msf.org, the supplies were called paltry and insufficient.

Judith Kumin is the UN’s High Commissioner for Refugees representative in Canada. The UN is one of the main sources of funding for MSF, providing the majority of funding for medical supplies and refugee camps.

“[Under Taliban rule] it [was] difficult for us to do anything in Afghanistan. It was very dangerous for our Afghan staff to work within the country,” says Kumin.

Tommi Laulajainen, director of communications for the MSF branch in Toronto, has been working with the group for 4 years.

“Since the Taliban have been overthrown it is much easier for us to expand our programs across the country. It is much easier for teams to move around.”

Even with the re-emergence of MSF, Shanks believes that the Afghan refugees will never return to the same Afghanistan that they have left.

“it was very hard for us to negotiate with the Taliban, but insecurities around Afghanistan still exist,” says Laulajainen.

“Afghanistan wasn’t like this, 30 years ago,” says Dr. Reza Baraheni, president of PEN Canada, a branch of the international group that supports authors who are persecuted for what they write; and a supporter of MSF, “Afghanistan used to be a country that had pride in itself. The Taliban have taken away Afghanistan’s dignity.”

Even though western countries including Canada and the United States have pledged $1.5 billion in support to Afghanistan, the rebuilding process will likely still be arduous.

Baraheni, who has been following the Afghan conflict for many years, says that to establish a new stable government, Afghanistan needs a government in which all ethnic groups of the country are represented. “Women, like 30 years ago, also need to take an active part within the country’s new government,” he says.

Baraheni lauds the work of MSF in Afghanistan, though his kudos are rather bittersweet.

“MSF is doing a great job in Afghanistan. They are true humanitarians. But ironically, I hope that some day Afghanistan won’t be needing them anymore.”

Leave a Reply