By Andre Mayer

The Horseshoe Tavern on Queen Street, is abuzz even at 4:30 in the afternoon. Inside, the adolescent thunder of Australian rockers silverchair is pumping from speakers. Two owners of Hamilton-based independent record label Sonic Unyon, Mark Milne and Sandy McIntosh sit at a table. Neither Milne, 26, nore McIntosh, 25, exude the haughtiness of corporate record executives.

Sonic Unyon was founded four years ago. They started the label for their band, tristan psionic, but their roster has now expanded to nine artists.

“You turn on the radio, and you don’t hear much that you like,” says McIntosh. “So there were a bunch of bands that we knew and that we’d been playing with, and because they were good, we thought maybe other people should them.”

Sonic Unyon artists treble charger and Hayden have enjoyed some commercial radio play, but on the whole, the label’s bands have not conquered the airwaves. Milne says many stations have told him that his music doesn’t fit their format. It doesn’t worry him.

“We don’t spend a lot of our days soliciting commercial radio,” Milne says. “It’s not really important to us.”

These words ring ironic coming from an up-and-coming Canadian band, especially considering that the government supports homegrown talent by forcing music radio and television broadcasters to play 30 per cent Canadian music everyday.

Last year, Canadian content regulations became a quarter-century old. In January, 1971, when the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications (CRTC) put into effect regulations to air one third of Canadian music each day, it was a protective measure against American and British artists who dominated commercial radio play in Canada.

As evidenced by independent bands, music trends put less emphasis on radio play. New artists are becoming harder to categorize and less likely to fit a conventional radio format. Call it the post-commercial radio era; with an influx of artists releasing material independently, many new bands aren’t willing to sell their souls just to be played on Top 40 stations. Now there are few hit stations left, and it reflects a trend amongst some up and coming bands that getting airtime, CanCon’s main focus, is no longer the be-all and end-all. The outdated government regulations are now making way for innovative private talent organizations to develop the music industry.

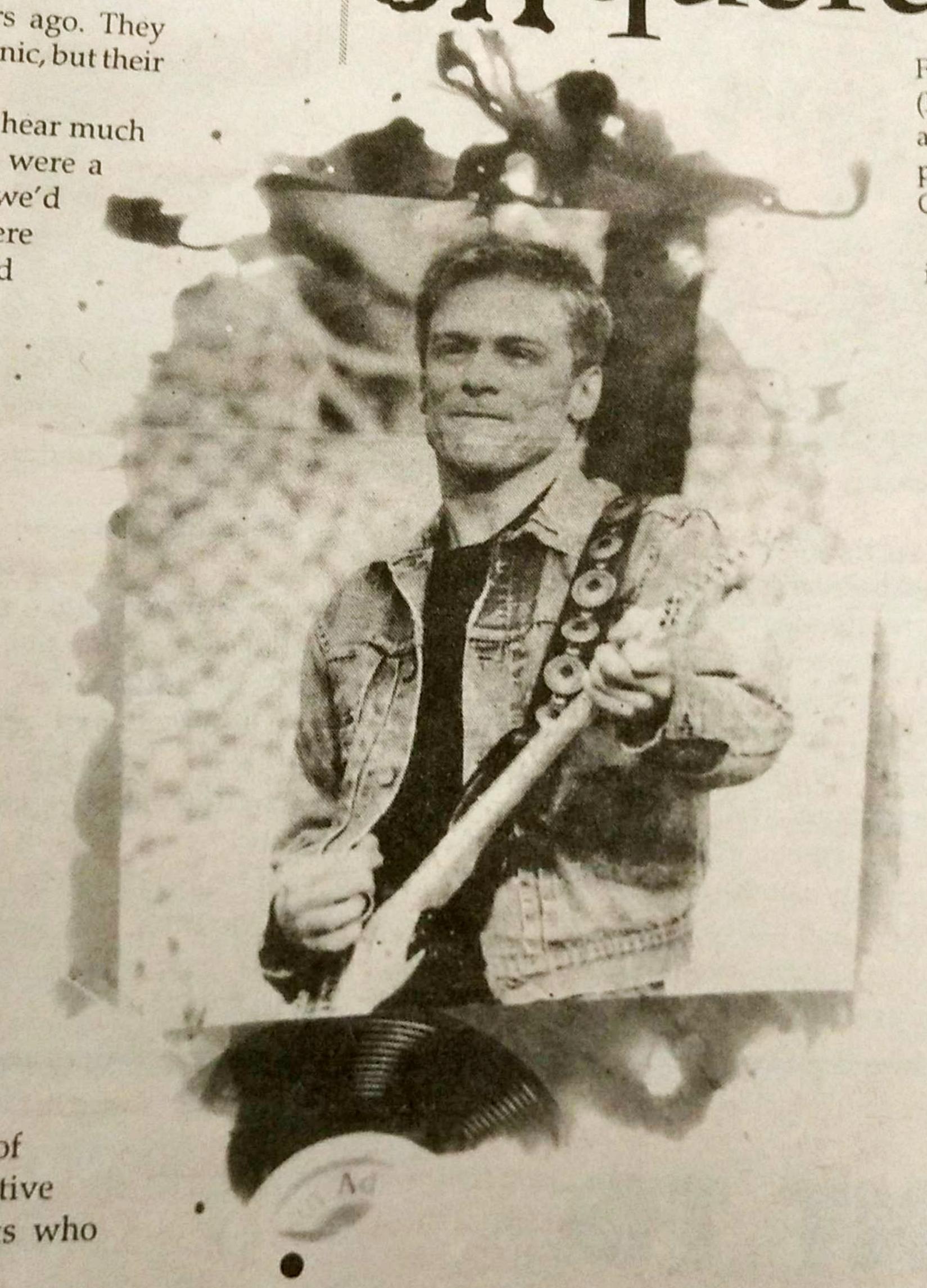

The reception area at Mix 99.9 is intimately lit. Portraits of international stars decorate the walls. Not out of place amongst pictures of Bruce Springsteen and Phil Collins is one of Bryan Adams, Canada’s most visible contribution to the international music scene, and a man whose damning views on CanCon are no secret.

JJ Johnstone, Mix 99.9 programming director: “I think at the time they were brought in, Canadian content regulations were necessary, and really did a number in terms of getting the Canadian music industry to where it is today, which is very healthy, in definite growth mode.

“But I think the business has been on life-support too long. It can breathe by itself now.”

In 1971, some applauded CanCon, but the regulations were also met with hostility. Many broadcasters were outraged, because American and British music was their bread and butter; some Canadian artists, like Burton Cummings and Ian Tyson, resented having their music propped up by legislation. Pierre Juneau, CRTC chairman in 1971, admitted the measures were more a “blunt instrument” than a long-term solution.

Perhaps the most defining moment in CanCon’s history came in 1992, when Bryan Adams condemned the regulations after his album Waking Up the Neighbours was deemed un-Canadian by CanCon standards. The Commission uses a point system, MAPL — which stands for music, artist, production and lyrics — and a Canadian must be responsible for two of these four for a recording to be deemed Canadian. Adams had written songs with a British producer and therefore didn’t meet the criteria for a Canadian recording. After the much-publicized acrimony between Adams and the Commission — Adams seethed that the legislation had “mediocrity [as] its biggest by-product” — the regulations were modified to include a clause that a Canadian who collaborates with a non-Canadian receives half the credit for music and lyrics.

However questionable its tactics, the Commission brought a music industry into existence.

But the CRTC knew how the industry was just a blueprint: the CRTC knew how the industry should look, but provided few tools. The 30 per cent rule sent broadcasters into a panic — if before 1971 broadcasters wouldn’t give Canadian artists the time of day, where would they find the required percentage? Broadcasters claimed there wasn’t enough quality music available to fill their quotas. So they ended up playing the few Canadian stars like Gordon Lightfoot and Anne Murray, until the stars themselves cried uncle.

“A lot of crap came out back then,” says Johnston. “The producers, talent developers, the whole talent machine had to be jump started.”

To combat the dearth of quality music, broadcasters created their own initiatives to foster Canadian talent, the most successful and enduring to date being the Foundation to Assist Canadian Talent On Records (FACTOR). FACTOR was founded in 1982, 11 years after CanCon, by broadcasters. It was a private non-profit organization that would provide assistance to Canadian talent.

“The Canadian music industry is a growth-export industry,” says it Executive Director, Heather Ostertag. The statistics are there to prove that you need to support this kind of industry, and [FACTOR] has played a vital role in stimulating the industry.”

FACTOR offers 12 loan programs. Its funding comes chiefly from broadcasters, but since 1986, it has also received funding from the government. In its 13 years, FACTOR has given almost $17 million to recordings for national distribution, and seen FACTOR-supported recordings translate into over $230 million in worldwide sales.

In light of what FACTOR has done for Canadian music, it is in the Commission’s interest to ensure its existence.

The CRTC forces radio stations to contribute financially to help promote the industry. In an attempt to “streamline regulations and Canadian talent development, in 1995 the Commission met with the Canadian Association of Broadcasters (CAB) to establish a mechanism ensuring that CAB continues to contribute at least $1.8 million annually to developing artists.

Lise Plouffe, spokesperson for the CRTC, says the amount a station contributes is mainly its own prerogative, but adds that “if their revenue is up from a previous year, we usually encourage them to contribute more.”

Stations must also incorporate talent development initiatives. Mix 99.9 does its part by staging the annual “Beachfest” which features new bands, and has in past years drawn up to 130,000 people. It also has an annual talent search which draws over 2,000 submissions.

But these measures are ultimately one-dimensional: the goal is commercial radio.

“We’re a hit-oriented radio station,” Johnston admits. “We look for brand names.”

As a label, Sonic Unyon’s focus is live performance, and their band are constantly touring. The bands also encourage fans to sign up at gigs for the label’s newsletter.

Because CanCon considers radio-play the measure of success, the CRTC does little to develop bands like those on Sonic Unyon. FACTOR, however, has responded by expanding to include programs beyond recording grants such as grants for management, tour support, marketing and video production. Several Sonic Unyon bands have received FACTOR assistance.

“We tapped into what was needed in the industry,” says Ostertag of FACTOR’s new program. “[FACTOR] has to stay abreast of new developments in the industry.”

But that does not entirely discount CanCon’s contributes. In the last 26 years, CanCon has produced a domestic industry, rescuing many artists from obscurity by putting them on the airwaves.

“Without CanCon, Canadians woudn’t have gotten a chance to hear Canadian music,” says Paul Spurgeon, legal counsel for the Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of Canada (SOCAN). SOCAN reports that between 1970 and 1976, royalties paid to Canadian artists more than tripled.

FACTOR continues to develop new Canadian talent, even if it never reaches commercial radio, while the CRTC remains painfully out of touch.

“CanCon will be around for a long time,” maintains Milne with a sigh, “and eventually we’ll figure it out.”

Leave a Reply