By Kenny Yum

The footpath in Toronto’s old Chinatown can barely cope with the noon traffic of elderly Chinese women, clutching bright plastic bags filled with vegetables and herbs. Younger Sunday strollers spill on to the roads to pass the pedestrian traffic jam, winding their way through the Chinese music shops, restaurants and supermarkets, all in a section barely longer than a city block.

Anchored at one end of the shopping strip, Toronto’s new Bank of China building, a mere four storeys tall, looks out of place in the city’s oldest Chinese meeting spot.

The building gleams with new wealth and respectability, a far cry from the old Chinatown’s laundromats, vegetable shops and restaurants.

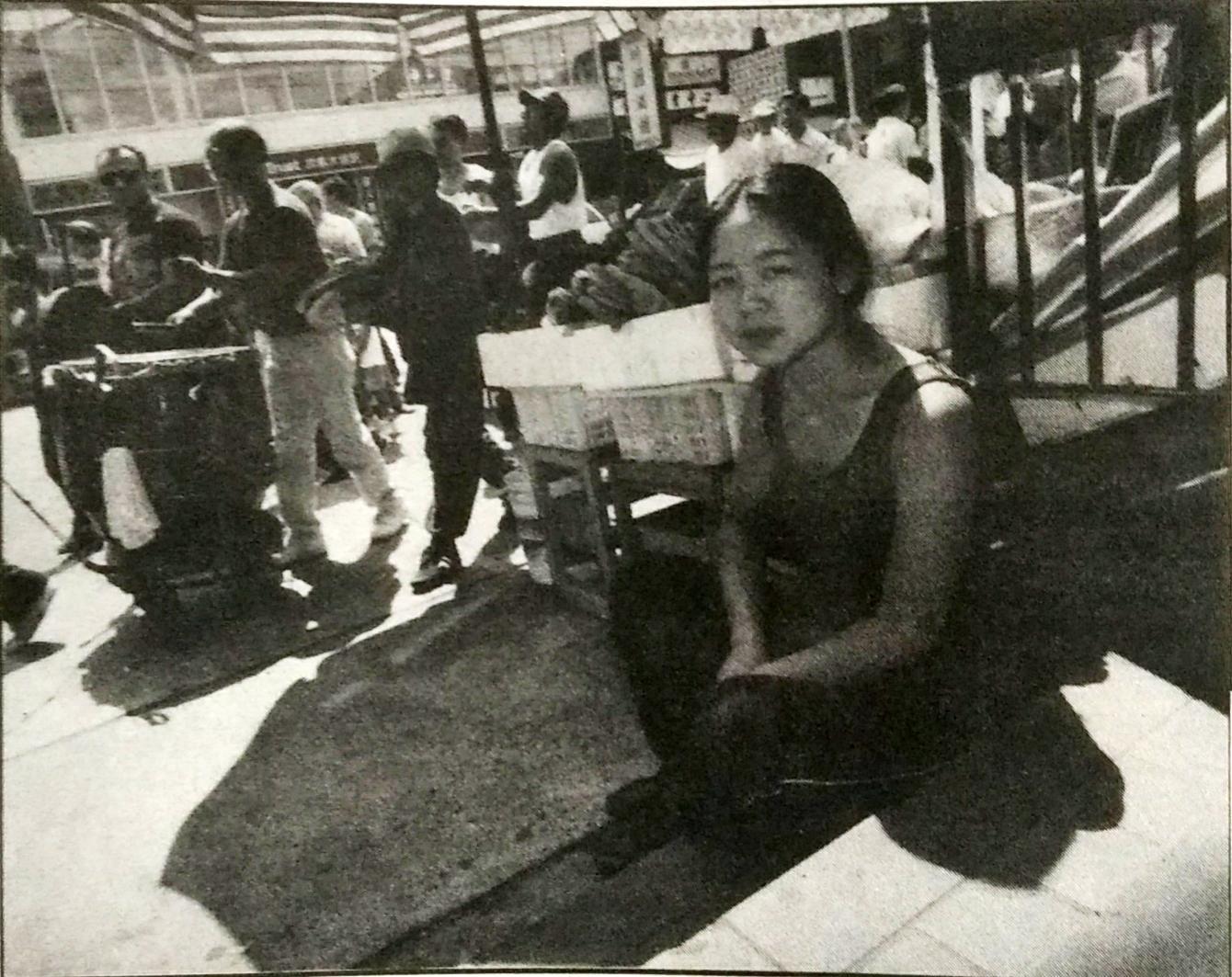

Claire Yao, and 18-year-old Canadian-born Chinese, enters one of the crowded restaurants along the narrow street and struggles to be heard over the Canto-pop and conversations in Cantonese and Mandarin.

“It’s totally traumatic ordering in a restaurant,” she says. “When you walk into one like this the staff immediately talk to you in English. I’m always going to feel like an outsider in that way.”

Like many Canadian-born Chinese (CBCs), Yao’s parents are from Hong Kong. Brought up in multicultural Toronto, she, like the other young CBCs, is stuck between two cultures.

A bamboo plant is hollow in the centre and splits into two sides at the end, two sides that never connect. An old Cantonese nickname in Canada refers to CBCs as a juk sing, or bamboo children, as they cannot properly merge with either the Chinese population or mainstream Canadian culture.

In 1993, more than 36,000 Hong Kong residents migrated to Canada. Canada’s total Chinese speaking population will soon top one million out of a total population of 30 million. For Hong Kong families, Toronto has remained a favourite destination. Most of the 400,000 in Metropolitan Toronto have roots in Hong Kong.

Yet for young CBCs, the increased visibility of a Hong Kong community in Toronto has fogged their own identity. For the 60,000-plus Canadian-born youngsters, recent immigration has changed the way they see themselves.

“It causes an identity crisis for kids,” says Ella Li, and English teacher originally from Hong Kong.

More than half of the 1,200 students at her North York high school are Chinese and most are recent immigrants from Hong Kong.

“The Hong Kong community is so big now,” says Gerwin Ho, 21.

“It’s hard to avoid and it’s in your face.”

Ho, who left Hong Kong 10 years ago, acknowledges that the large Hong Kong youth community has affected CBCs’ attitude towards Hong Kong culture.

“The trend is that they are trying to learn more about Hong Kong,” he says.

More CBCs are taking Chinese language lessons as part of their elementary and high school education. Tam Goossen, a Toronto school trustee from Hong Kong, says: “Some of the students are learning Chinese as part of their identity search, which is very legitimate.”

Getting into the “Hong Kong culture” usually consists of listening to Canto-pop music, frequenting Chinese malls to watch movies and hanging out in karaoke bars. And, of course, dressing like Hong Kong youth.

It is a Saturday afternoon at the Canadian National Exhibition, the country’s largest annual summer fair held in Toronto. A youth orchestra from Taiwan plays traditional music to a crowd of mostly Chinese Canadians, followed by dragon dances, martial arts demonstrations and ribbon-cutting. The fourth Chinese Heritage Day in Toronto is starting.

Two young people saunter on stage to announce the start of a karaoke singing contest. Chinese Heritage Day? A Chinese teenager wearing dark shades struts on stage, arms flailing, and sings Faye Wong’s “Dream Person.” So much for culture and heritage.

Ten years ago, any young Chinese in Toronto would have associated their cultural roots with Chinatown, dragon dances and dim sum brunch. But Hong Kong youth culture is making a major impact in the 1990s.

Gladys Chu came from Radio Television Hong Kong four years ago to produce an entertainment program for Toronto’s Chinese population.

Her Chinese Entertainment Plus has evolved into a popular weekly youth entertainment show.

“A lot of people who come from Hong Kong want to see Hong Kong-style programs,” Chu points out.

“We are aiming for young people who can understand Chinese,” says Leila Luke, 22, one of the hosts.

The show airs segments on the latest North American entertainment scene, plys recent music from Hong Kong. For the most part, it seems the content targets Hong Kong youth.

There are attempts to teach newly-arrived youth about Canadian culture both in school and through the media, but the two groups do not exactly see eye to eye.

“I don’t see much friendships going on between the two groups because the cultures are different,” says Li.

“The clothing, the fashion and interests are all different,” the teacher adds.

Culturally, CBCs are a lot more mainstream than Hong Kong youth.

The result is a marked polarization between the CBCs and Hong Kong youth.

What young Canadians see in Hong Kong youth is “show-off wealth.” It is a perception sometimes based on stereotypes and rumours rather than tangible truths. “Chinese Canadians think ‘who the hell are they? Arrogant and rich and they come with their cars,’” observes Yao.

Many recent Hong Kong migrants are indeed more affluent than their predecessors. Before the ‘90s, Chinese came to Canada with little money to build a future for their families.

The new money leads to some tension within the community — the old against the new, even late ‘80s immigrants against the newly arrived ones.

“There are a lot of Chinese Canadian who have grown up here who feel resentment because of the new Hong Kong immigrants,” stresses Yao.

“They don’t think of themselves as Canadian at all,” maintains Chan. “Some just plan to go back, using Canada as an escape route. And I’m insulted about it.”

It is a belief shared by other Chinese Canadians. The Chinese council’s Ma says it is up to Hong Kong parents to make up their minds: should they stay or should they go? “Many have not been able to decide once and for all whether they are going to stay, and that’s unsettling for the kids,” he argues.

Unsettled as they are, Yao maintains at the very least, Hong Kong youth can cling to their culture and sense of identity. Even in their native land, CBCs are a group still working out an identity. “They [Hong Kong youth] have their cool subculture that I’m really jealous about.”

“A lot of Canadian-borns don’t have that kind of security and being able to fit into a group.”

But Ma thinks young CBCs are now looking back at the Chinese experience in Canada, which fates to the late 19th century. From novelists and artists, they are launching their own movement. Chinese Canadians are appearing in politics, the arts and even the mainstream media.

Despite their inability to fit in with Hong Kong youth, young CBCs still serve as a go-between for the newcomers and non-Chinese Canadians.

Similarly, young CBCs have closed the gap between the traditional Chinese and Canadian society. “Actually, I think it’s an advantage I was born here because I can cross over to both sides whereas one side cannot cross to the other,” she says.

For Chan and other CBCs, the nickname juk sing is not a sign of weakness, but more of a confirmation of their role as the first real generation of true Chinese Canadians.

Leave a Reply