By Giselle Culver

It was a 1972 Cadillac Sedan de Ville. Nineteen feet of emerald green metal, the colour of dragonfly wings. Rounded edges, creamy leather seats. A little bit of rust here and there. Who drive that? I had to know. It belonged to the exuberan Lars. He had rigged the behemoth to start when he pressed the cigarette lighter, bringing forth the distinctive sound of the low, masculine engine clearing its throat: ha RUM rum rum rum rum rummmmmm. I was hooked — on the car and Lars.

Beginning with a baby blue 1965 Ford Fairlane 500 with moose antlers tied to the hood, Lars has limped a yearly procession of old cars from British Columbia (where the mild weather preserves them) through salty winters in Ontario. He bought the Cadillac for $700 in Matsqui, B.C., trading in a 1970 Lincoln Continental Sedan (which cost $320 the year before). He wants people to think “here comes wild Lars in his old crazy car.” Lars is a character in a road movie, a movie where every person and place has something interesting about the, and a cool car — falling apart though it may be — gets you there in style.

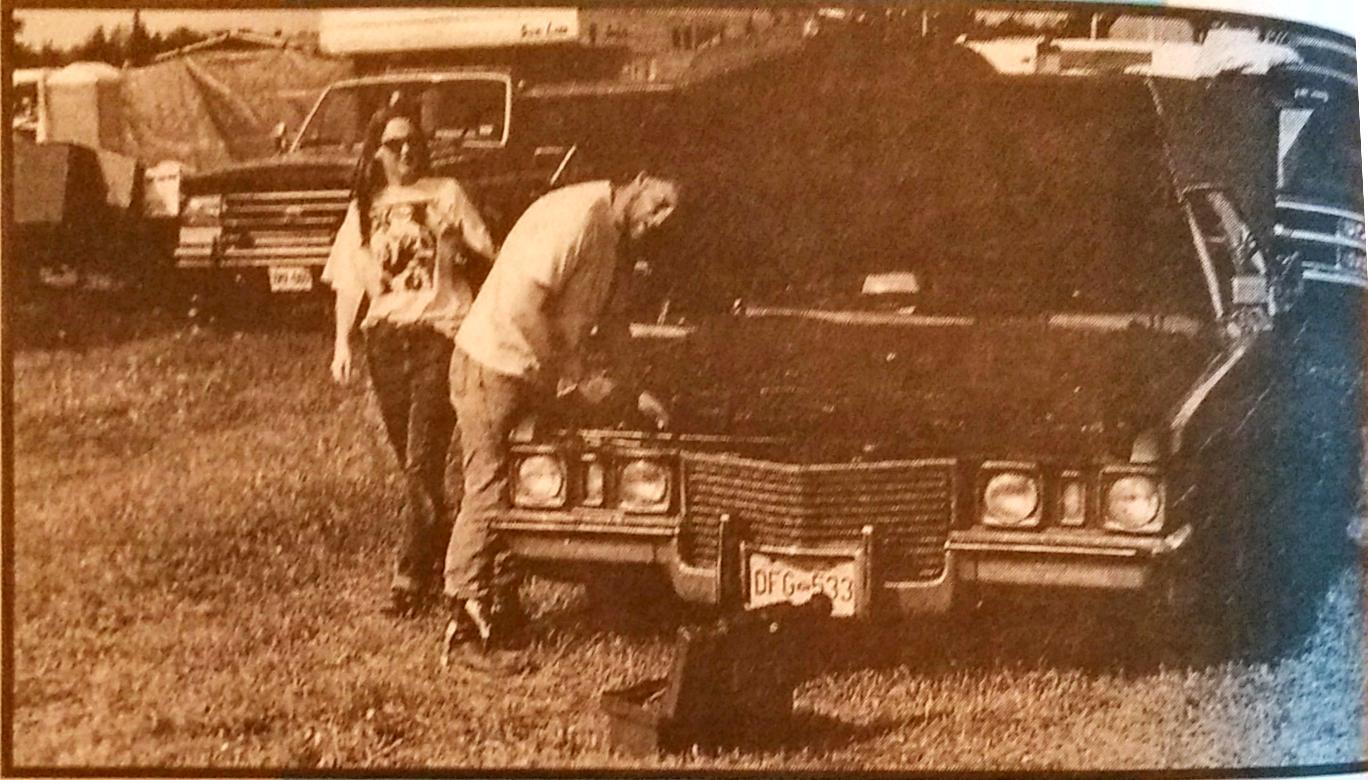

We took the Cadillac to the Barrie automotive flea market, a twice-yearly gathering of vintage car enthusiasts. For a three-day weekend every June and September, the fairgrounds 20 minutes north of the city are packed with ancient cars and ancient car parts. I wandered around happily in the fading afternoon light, in love with every old car I saw, as Lars tinkered with the Cadillac, getting it ready for a road trip later in the summer. It would be the Cadillac’s final journey.

Toomas Westerblom, who’s 23, drives a red ‘66 Dodge Polara he bought in Fernie, B.C. for $600. When he and his brother Taavo spotted the car they were driving a Ford Taurus station wagon. “What the hell is that!” he said. They wanted something that suited their personalities and the Polara had character. “It was stylin’!” Toomas says. Toomas’ older brother, Peeter, has a ‘64 Dodge Polara he bought for $250. “They’re different, unique. There’s not a lot of them,” Peeter says. “And you get more looks driving them.”

Whenever Toomas goes out to buy parts, the shop owner always looks under the hood and asks him what he’s doing to the car lately. “People think it’s cool if you’re maintaining an old car yourself,” says Peeter. “People say. ‘I used to have one just like it. I took it to the junkyard 10 or 20 years ago. You’re still driving it?’” For the Westerbloms and for Lars, cars are meant to be driven. Unlike most old car enthusiasts, they drive their cars in winter, instead of storing them from October to April. But of course, their cars aren’t exactly mint condition. The rear wheel bearings on Toomas’ Polara have been a problem from the beginning. “Eventually they’re going to blow. I’ll be driving down the highway and they’re just going to give and the whole car’s going to go off the road,” Toomas says. And sometimes old cars come with interesting quirks.

Toomas runs out of gas unexpectedly because his fuel gauge doesn’t work. He makes sure he has a jerry can of gas with him all the time, although he learned that lesson the hard way. Driving to his cottage late one night he ran out of gas at the beginning of his cottage road turn off. It was a five mile walk. The odometer and speedometer don’t work either. It’s hard to find dash parts for such and old care to be able to fix the problem, but then engines of old car are a lot simpler and easier to fix than the current compact imports. “What it comes down to,” Peeter says, “is old cars are built better than new cars.”

The electrical system of Lars’ Ford Fairlane overloaded one night in Saskatchewan while he and some friends were driving to B.C. Almost all the wires and switched burnt or blew out, so they had to make switches. “We used paper clips, tin foil, pocket knives, an ashtray from a restaurant, rubber bands, telephone wire and lots of duct tape ro rewire the car,” Lars says. “Every time you wanted to use the turn signal you had to push a paper clip to the left or to the right. To make the brake lights work, you had to push a paper clip onto the pocket knife mounted on the dash. And every time you wanted the high beams on, you had to move the ashtray on the dashboard from one position to another position with tinfoil underneath it.” Amazingly, the jury-rigging lasted the rest of the trip. Lars had to teach the guys who bought the car (for $12) how to use the system.

Lars and the Westerblom brothers are somewhat scornful of older people who collect cars as a hobby and want their cars in mint condition with the bolts in the original factory position. “I like home customations,” Taavo says. “Like your cigarette lighter in your Caddy,” Peeter laughs to Lars.

Unfortunately, it was a “home customation” that killed the Cadillac. At the flea market in Barrie, Lars made a number of zany improvements: he cut a hole in the dashboard and fit a home stereo system; he added reading lights; he installed a PA system with a CB and a huge speaker under the hood so he could talk to people outside the car. He also — and this is what destroyed the engine — removed the overflow canister to make room for an extra battery so he could have music and lights while camped at night without having to drain the car battery. In Virden, Man., the engine overheated and the head cracked. There was nothing to do but sell the car for scrap metal and come home.

Back in Toronto, Lars bought an ‘86 New Yorker — boring but cheap. We had a week before the news school term began, a week to drive as far as possible, in homage to the Cadillac. We decided to visit a friend in B.C. All we knew was he lived on Faraway Road somewhere outside 100 Mile House.

We flew past the Canadian Shield, stopping only to wait for a team of drillers to blast rock on the highway. I got out of the car and walked on that bedrock foundation — the landscape of my life til then — where lichen flourished and mossy scraplings clinged hardily. It crunched under my feet, sun-crisped yet soft. My footsteps were imprints as I looked behind me. After the shield dwindled away, I felt the sky growing larger in my head. And I realized this country is vast; the world much more vast.

The absence of motion woke me early on the fourth day; we had stopped for gas. I sat sleepily in the back seat, reaching for my glasses. I felt the mountains before I saw them — a heavy dark presence rising around me. Salmon Arm was a bowl of milky glass lights in the 6 a.m. chill. We drove on, looking for a road far away.

Leave a Reply