By Allan Woods

It happened in her history of design class. Chriss Fort was sitting at a desk, barely listening to her instructor as she absent-mindedly doodled on a sheet of paper.

Her imagination was drawn back to fairy tales from her childhood as the lines and figures she was sketching began to take shape. Soon, sitting before her was a drawing of a woman dressed in an elaborate gown. “I knew then that it would be my fairy godmother dress.”

Two years later, in her graduating year at Ryerson, Fort is bringing that fantasy to life with her Cinderella-themes Mass Exodus collection.

“Cinderella is a timeless story,” she says. “When the audience sees it on the runway—when they see the prince holding the glass slipper—they’ll know right away what it is.”

Hours of painstaking sketching, pattern-making, cutting and sewing have culminated in Fort’s five-costume collection. There’s Cinderella, the king, queen and prince and the fairy godmother.

The last is the jewel of the ensemble. The gown is pale blue, almost grey in colour, with a 5-foot-wide skirt. Tiny beads are sewn onto the bodice in the shape of flowers, and rhinestones cover the skirt.

“Under stage lights, the fairy godmother will look like a disco ball,” Fort says, gazing at the dress hanging on a “judy,” or mannequin, as she makes adjustments. “It’s eye candy.”

There’s only one week left until showtime. For fashion students in fourth-year design and third-year marketing, Mass Exodus, the biggest student fashion show in Toronto, is the most important event of the year.

When the models slip into the clothes and prance down the catwalk in the Ryerson Theatre on Tuesday and Wednesday, they will be upholding a 32-year tradition. The first Mass Exodus, Tango, was held at Palais Royale on the Toronto waterfront in 1968.

Today, the show attracts members of the Toronto fashion industry in search of fresh, young talent, and reporters and editors from the likes of Flare magazine and Fashion Television.

But before there were garments or models to wear them, before there were stage lights or even a stage, there was a group of students with a few years of training, a couple of ideas and a reputation to live up to.

“Mass Exodus is the culmination of four years of work,” Fort says.

Last semester was a preparation period. Designers were sketching their creations and submitting colour illustrations of their collections. Marketers began meeting the first Thursday they returned to school at a weekly two-hour class.

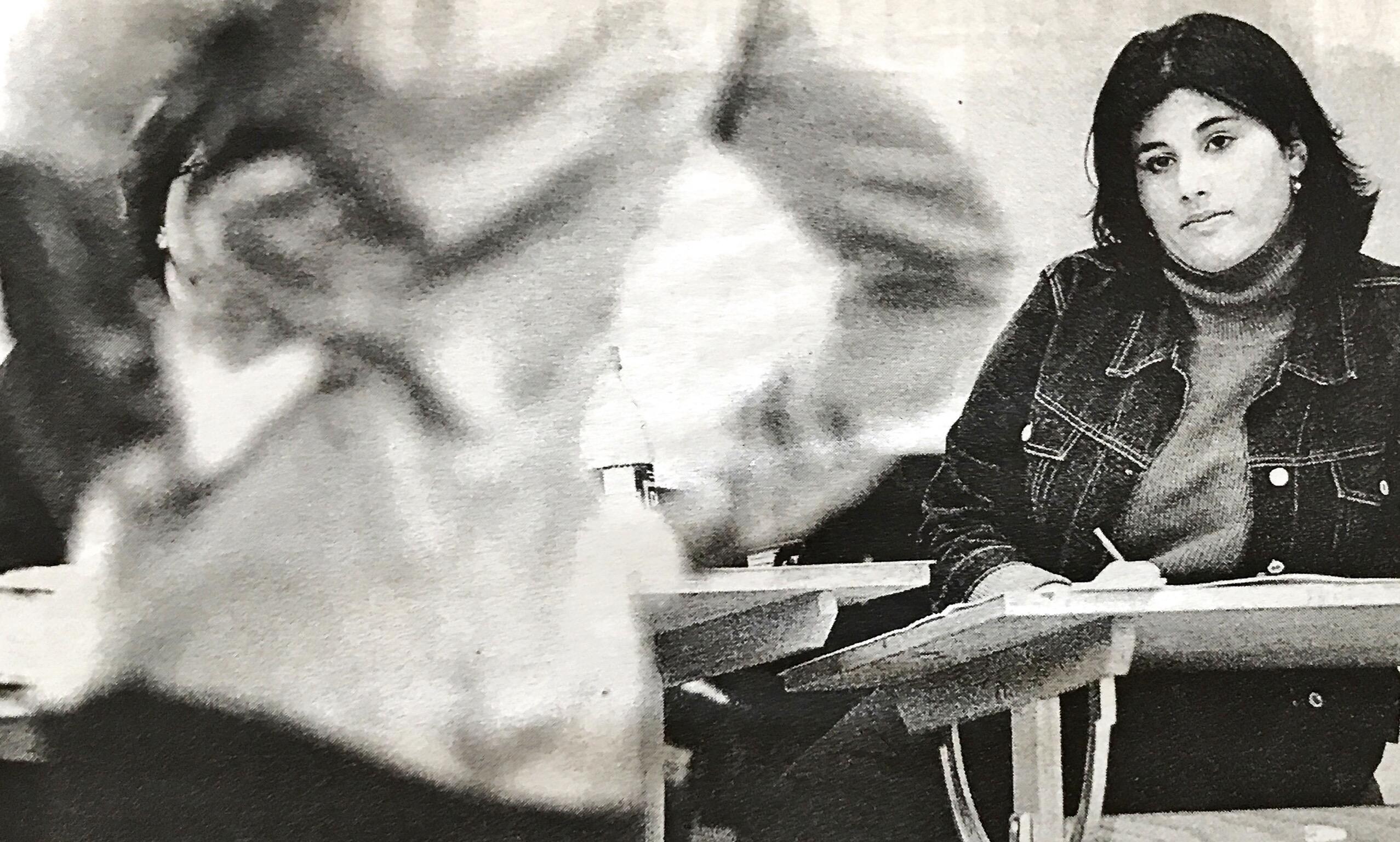

For Jessica Sammut, those early days feel like years ago.

At their second-meeting, the marketing class elected Sammut, 21, co-director of the show.

“I had no idea what a co-director was really about,” she says. In her first year, she was head of public relations. In her second year, she was involved in PR and fundraising.

As co-director, Sammut has entered centre stage. Along with director Michelle Lukawitz, 23, who is running the show for the third straight year, Sammut has helped bring 250 people together over the past eight months.

The designers, the clothes, the models, the stage, the sponsors—”It’s been a struggle, but I think it’s been a really, really good learning experience.”

All these pieces will come together at Jigsaw, the name of this year’s production.

Jigsaw was lifted out of a trade magazines, where is was used to describe the different materials, fabrics and textures forecasted as trends for the next season.

“Taking it one step further,” Sammut says. “Jigsaw can be the different elements brought to the show by the designers, because each has their own personal edge. The elements come together to make one big picture, which is Mass Exodus.”

Last semester, marketing students were busy preparing schedules, setting timelines and drawing up budgets, essentially planning the work that would go into making Mass Exodus a reality.

When they returned in January, they were joined at their Thursday afternoon meetings by theatre technical production students.

At those early gatherings, a line could be drawn down the middle of the room, separating marketing from theatre students. No one thought to cross it.

Lukawitz and Sammut ran each meeting, asking for progress reports from each department.

“Okay Krystal, what happened this week with the program?” Lukawitz begins.

“Well, we finalized the design for the cover and we’ve figured out what we can take new sponsors until quite late in the show,” reports Krystal Milson, who is responsible for producing the show’s program.

“Okay,” Lukawitz continues. “Nicole?”

Nicole Mahabir is head of public relations. “I’ve just finished the press releases, but I don’t have them with me,” she says. “I’ll bring them tomorrow. Oh, and we may have Energy 108 for the after-show reception.”

This piques the interest of half the group—the marketing student. The other half looks on in silence.

It continue this way through each member of the marketing class, then with 10 minutes left, theatre students get to run through what they’ve done.

Sammut has trouble remembering some of their names.

Her mind is somewhere else. She’s thinking ahead to casting calls, where an entire semester of sitting around planning will finally be put in motion.

Agencies have been called and pink posters have been put up around the school. Anyone interested in modelling for Mass Exodus is asked to attend the first casting.

At 6:30 on a Wednesday night, they begin to arrive. It’s exactly three months until showtime.

Dance music blares from the door of a long classroom on the second floor of West Kerr Hall. Inside, desks have been pushed against the walls to make room for a 10-metre runway—essentially two X’s taped to the floor at either end of the class.

In a room across the hall, Julie Ball and Natasha Williams snap photographs, take measurements and assign numbers to the aspiring models, who then wait outside the door for their turn on the runway.

Jessica Addario, head of choreography, opens the door, brings a model into the room and explains the 30-second procedure: “It’s very simple. You will walk from the X at the back of the room to the X at the front of the room. There you will pose, pivot and return to the back of the room. Okay?”

Sammut, Lukawitz and half a dozen other marketing students sit at a long row of desks at the end of the catwalk, noting each model’s strengths and weaknesses.

“Too short,” Sammut writes of one model.

“Nice smile,” of another.

“No,” she scrawls in her notes.

After almost three hours, Addario calls in the next model and the girls erupt in cheers.

“Marcus!” they squeal.

Marcus Peros, a third-year fashion design student, was a model in the second-year men’s wear show.

The music starts Peros walks to the front of the room and strikes a pose. With his hands in his pockets, tall frame and curly blond ponytail, he looks very GQ. He smiles, gazes across the desks, pivots, and returns. The panel cheers for their friend as he opens the door and leaves.

“Guys,” Lukawitz reminds them once the door is closed. “We can’t cheer like that. The models outside can hear us in here and they’re nervous enough as it is. We have to be professional.”

They sober up and the casting continues.

Almost 100 models walk by them in a four-hour span. When they leave, the marketing students pull their chairs from behind the desk and form a semi-circle around Lukawitz. One by one they review the models. Who to keep? Who to let go?

They’re working from scribbled notes and a list of types the 43 designers have requested for their collections. Flat-chested. Ethnic. Black. Pale-skinned. Asian. European. Sporty. Exotic. Tattooed. Trashy. Bald.

The problem is they are choosing from models who are mostly white, blond and the perfect size six. And few male models have come to the audition.

“I have a lot of issues with these girls looking different than they do in their pictures,” Sammut says. Some of the models bring professional composite cards with their photographs and measurements, but the pictures can make a 15-year-old girl look 21.

A frustrated Addario blurts out what everyone is thinking: “A little hair and makeup can do anything.”

In a few short months, a handful of these models will be the face of the show. They’re the ones the audience will see, not the designers working all night in the lab or the marketing and theatre students at countless meetings and brainstorming sessions.

The audience doesn’t have to worry that stage designs are still being finalized, that more funds need to be raised, that $10, $15 and $20 tickets must be printed and sold.

Lukawitz has to worry. So does Sammut and the class of almost 50 students, who will put in long hours over the next few months to make Jigsaw a success.

Just when they start to feel overwhelmed, anxious about not having enough male models or working with the talent they’ve seen at the castings, they remember the advice of Peter Duck, the show’s faculty advisor. “You know in a very short time if a model is suitable. You can teach them how to walk. All you’re looking for is the face and the body.”

Duck has seen the show develop from start to finish for 22 years. That’s why he stays calm when everyone else gets stressed. That’s why he sometimes smiles when problems arise close to deadline.

At crunch time in late February, designers can be found in the fourth-year fashion lab in West Kerr hall 24 hours a day for day at a time. Those who don’t meet at the strict deadlines can’t show their collection at Mass Exodus.

“At the start of the year things are a bit more relaxed,” Danielle Mulvaney says as she patiently threads a needle to put the finishing touches on a bridal gown. “You might only spend he occasional night in the design lab.

Her instructor will mark the gown and the rest of her collection in less than 10 minutes. It’s her third straight day in the lab. “You get used to it.”

This is the first time design students have had to create a collection of five garments.

Off in the corner of the lab, Chriss Fraser, 21, stand facing each other. Their hands are in front of them at chest height, and though they almost touch, do not meet.

They are an odd sight. Fort is a little over five feet with short, bright green hair. She wears jeans, a long T-shirt and no shoes.

Fraser is a head taller. His black jeans, held up by a pair of black suspenders, are tucked into a pair of clunky motorcycle boots.

The couple push an invisible wall between them, straining and exerting themselves for minutes without moving. They stare into eachother’s eyes until finally, Fort stops pushing and loudly exhales. They hug.

This is how Fort releases stress. It’s how Fraser helps her stay sane.

Fort spends 12 to 16 hours a day in the design lab, although a third of tat time can be spent just talking.

She loves to talk. “Sometimes when I spending days in the lab, I’ll page Colin just to hear his voice.”

Her passion for costume design was sparked after coming to Ryerson. By second year she was developing her skills working with the Oakham House theatre society.

A girl named Annie Adams, who was a year ahead of her was directing a play called I Hate Hamlet. For approached her and asked if she had a costume designer for the show. She didn’t “You’ve got one now,” Fort told her.

They became friend sharing a passion for the theatre and fashion. “We were involved in plays together,” Fort says. “And we would pop in on each other in design lab to give each other a hand.”

Adams died of heart failure in March at the age of 25, on the same day she completed her Mass Exodus collection.

“Annie had a very strong life force,” Fort says. “You couldn’t meet her and not love her.”

Fort’s collection, Four Score and Seven Years, is dedicated to her memory.

“Clothes make the man. Naked people have little or no influence on society.” — Mark Twain.

In mid-March, there is a lull in the Mass Exodus production as fashion marketing students focus on the class competition sponsored in McGregorSocks. In groups of three, students must prepare a market a campaign for a line of McGregor loungewear.

It’s two days until the winner of the $1,500 grand prize is announced. In the Mass Exodus office in the basement of West Kerr Hall, Sammut, Lukawitz and Amanda McAlpine are putting the finishing touched on their presentation.

“When you wrote in your planner that you’d be working on McGregor all night, you didn’t achieve it?” Lukawitz asks when Sammut wonders aloud how much longer this will take.

The hard work—research, brainstorming, drafting business plans and studies figures—is complete. The only thing left to do is present the collection in a way that gives the clothes style and a bit of attitude.

Sammut trims a piece of paper with their slogan, “Philosophy of You,” while Lukawitz and McAlpine paste pictures of male baby boomers, their target market, onto black bristol board. The collage is highlighted by Twain’s quote, with diagrams, colour schemes and patterns for their collection below.

In the back corner of the room, sitting on a shelf beside the desk, is a box the size of a small television. A few pieces of paper lie over it, almost hiding it from view.

This is the model stage for Mass Exodus. It’s stripped bare. The runway lies upside down on a nearby shelf. Panels that slide and lift to reveal the models on stage are nowhere to be seen.

Mass Exodus isn’t the marketing students’ focus right now.

Down the hall is a group of theatre production students who are thinking about the stage. Soon they will have to construct it.

By late March, the lines have blurred at Thursday’s meetings, so that reports alternate between fashion and theatre students.

Chris Greenhalgh, theatre production’s head of audio, has begun recording the music for each collection. He is working with Jocelyn Juriansz, fashion’s head of music to prepare a recorded copy of the entire show. As their work progresses, their reports become a dialogue of what’s been done and what’s left to do.

Addario, fashion’s head of choreography, and Dany Tacou, theatre’s head of lighting, report everything is on schedule and under control on their end.

Then theatre production student and technical director Olwyn Davis raises a problem. A silhouette screen fashion students wanted for several collections won’t fit on the stage. “We’ve looked into using a machine that create a haze instead,” Davis says.

“But I’m concerned we’ll lose the effect,” a fashion student says.

“We’ve got pretty good lights and special effects,” Davis replies. Tacou nods in agreement. “We won’t lose the effect.”

Peter Duck intervenes. “If this were a professional client, how would you be trying to sell them on the change?” he asks Davis. “The haze machine is more expensive, isn’t it?”

“We would probably be coming to you with a slightly better, slightly more organized presentation than the one we’re giving now,” she admits. Everyone laughs.

The theatre product students see the fashion students as clients. “They hire us to do what they want,” production manager Jaime Caya says. “We tell them what can be done and then we do it.”

Much of the lumber for the stage and runway is re-used or donated, as are headsets for theatre production students and gift packs for models.

In past years, Mass Exodus cost between $10,000 and $16,000 to put on. Duck says renting space and paying models and crew for an industry show would cost upwards of $30,000. Mass Exodus avoids these expenses by offering companies free advertising at the show in return for donations and sponsorships. Models work for free.

Nadine Hernandez says fundraising has been difficult. “You have to be resourceful,” she says. “And you have to be really nice. ‘Hi. Let me tell you what’s in it for you,’” she mimics.

The countdown begins—less than a month until showtime.

Designer’s collections are complete and stored next to the Mass Exodus office in “the cage,” a bright, clean room named after the green fencing that runs along its perimeter. A table in the middle of the room is covered with thick black binders that hold designers’ instructions for each outfit.

McAlpine is in charge of fittings on this Sunday morning Tanya Poole, Julie Ball and Natasha Williams busily work the room, grabbing garments out of their bags inside the cage, dressing models and noting what alterations need to be made.

A male model holds up a tight white shirt with an over-the-shoulder pouch attached to it designed by Hin Luu. He can’t figure out how to put it on. Ball expertly slides the shirt over his torso and reaches for the matching white pants.

“Hey. These pants are dirt,” Ball says, holding up to show everyone what looks like grass stains on the leg.

“I think they’re supposed to be that way,” McAlpine says without looking over from the model she’s fitting. “Can someone get the technicals out?”

The technical instructions should say whether the designer intended the pants to be dirty, but they don’t. “That’s pretty weird,” Ball says, helping the model slip the dirty pants on.

At the table, Natasha Williams makes a note: “Clothes are dirty. Are they supposed to be that way?” She files it away in a stack of papers and moves on to the next model.

Another Sunday morning, two weeks until showtime. About 50 models meet for a four-hour rehearsal in the same classroom where they auditioned several months ago.

This final stage is meant for fine tuning. Tickets are being sent to people in the industry and final touches are being put on the stage. Dress rehearsals will be held Tuesday afternoon before the gala show for family and friends, which is almost sold out. Wednesday’s show is for press and industry.

The models stand in a semicircle around the miniature stage. Everyone has a diagram of the runway and an outline of designers’ instructions for their collections. The models have to know exactly how everything works.

Like a puppeteer, Addario stands above the stage and manipulates panels attached to wooden sticks, revealing black spaces on the otherwise white stage.

“This,” she begins. “Is line six—the panels move up and down. This is line nine—the panels move in and out. This is line 12—this panel moves up and reveals the stairs.”

After the demonstration, Lukawitz takes two groups of models into the hallway to practice walking. “When there are two groups of two, you will pass each other as if you are driving a car—on the right-hand side,” she says. “When there is a group of three and a group of two, the two pass through the three.”

Several models roll their eyes, annoyed they’ve given up a Sunday morning to be told something so elementary. If Lukawitz notices, she doesn’t let on.

In the room, a runway has been set up with two X’s on the floor, just like at castings. The models take their spin on the catwalk, dressed in blue jeans, running shoes and T-shirts.

They aren’t a collection yet. Only the clothes can do that.

“If you put an actor on stage in jeans and a T-shirt, they are only themselves,” designer Chriss Fort says. “When you put them in a costume, they actually become the king or queen.”

No, their crowning moment isn’t here yet, but it’s close.

Lukawitz can see it.

“You just fell off the runway,” she says to a girl at rehearsals when she steps over a taped line marking the end of the runway.

Sammut can see it, too.

“On the stage itself, all I see is white space,” she says. “Because of the special effects in the show, there will be points of intrigue where that white space comes to lie.

“I see the models walking out with their attitude and their expression. Add to that the expression of the draments—it’s going to be a spectacle.

“I think it’s going to be incredible.”

Leave a Reply