Questions linger after glimpse of Scientology

By Claudia De Simone

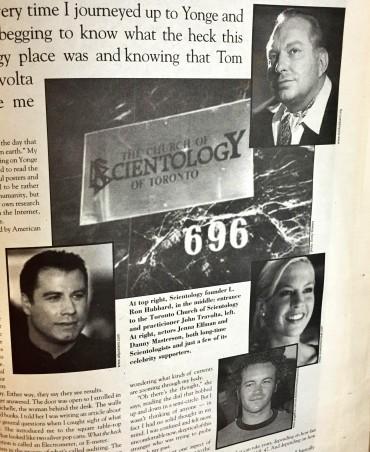

The sign wooed me every time I journey up to Yonge and Bloor. My mind was begging to know what the heck this Church of Scientology place was and knowing that Tom Cruise and John Travolta were members made me want to find out.

The red letters on a rotating sign read: “On the day that we can fully trust each other there will be peace on earth.” My eyes followed the window was I strolled by the building on Yonge Street, south of Bloor Street. This time, I stopped to read the display in the window. There were a few colourful posters and some pro-Scientology articles, but I found it all to be rather vague. They said they have all the answers for humanity, but didn’t explain any of them. So I did some of my own research and found a wealth of information available on the Internet, both glowingly positive and scathingly negative.

Scientology is a religious philosophy founded by American science fiction writer and philosopher LaFayette Ron Hubbard (1911-1984). His publication, Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health released on May 9, 1950, initially earned Hubbard world attention, providing what seemed to be a workable approach to the problems of the mind. Scientology aims for a civilization without insanity, criminals or war. It sees humans as spiritual beings. And L. Ron Hubbard claims to give exact answers those abstract questions — like: why we are here? — that humans have toiled with for hundreds of years. No clear cut answers were provided to me, however. I was given a sample of the religion’s practices, but I guess it’s a matter of buying Scientology-related books and taking courses to acquire this knowledge. Scientologists say that the religion is only real because the individual observes changes for himself. Scientology doesn’t tell it’s members how to worship, but some do choose to pray. Either way, they say they see results.

My dozens of questions were aching to get answered. The door was open so I strolled in to be greeted with a hearty ‘hello’ from Michelle, the woman behind the desk. The walls are covered with shelves of L. Ron Hubbard books. I told her I was writing an article about Scientology and I started asking her some general questions when I caught sight of what I looked like a weird science experiment. She introduced me to the square table-top contraption attached to wires leading to what looked like two silver pop cans. What the heck are these for? I’m wondering. The contraption is called an Electrometer, or E-meter.

The E-Meter is used by church ministers in the process of what’s called auditing. The goal is to locate areas of spiritual distress for the person being audited — the preclear, or a person who has not reached Scientology’s ultimate state: clear. It passes a tiny current through the preclear’s body. Michelle says this current is influenced by the mental masses, pictures, circuits and machinery in my mind. She explained that when I think of something as I grip the cold metal cans, these metal items shift and this registers on the meter, measuring my so-called reactive mind. Scientology’s official website explains this as “that part of the mind which works on a totally stimulus-response basis, which is not under a person’s volitional (voluntary) control, and which exerts force and the power of command over his awareness, purposes, thoughts, body and actions.” It is believed that the reactive mind is what holds humans back from experiencing the present. We react to events in life based on our past experiences.

During a one-on-one auditing session, the trained auditor asks the preclear, questions about his or her past until they are answered fully and the preclear is satisfied with the answers. Michelle says auditing helps people become more aware of themselves and their surroundings. But I was nervous — I felt like I was just letting the auditor in on my secrets. The woman’s dark grey cherub earrings dangled as she asked me who I hated most. My hands gripped the cans and I’m looking out the window facing St. Mary Street, wondering what kinds of currents are zooming through my body.

“Oh there’s the thought,” she says, reading the dial that bobbed up and down in a semi-circle. But I wasn’t thinking of anyone — in fact I had no solid thought in my mind. I was confused and felt more uncomfortable now, sceptical of this stranger who was trying to probe through my past.

Auditing is just one aspect of Scientology. It helps one get to the religion’s ultimate goal: Clear. This is when one’s reactive mind is gone, a process that can take years, depending on how fast one wants to move, said Scientology volunteer, Robert Hill, 47. And depending on how much money you’re willing to fork out for courses and auditing.

“The reactive mind is the only thing that’s wrong with humans. We’re all basically good,” he said.

The auditing fee in Toronto is about $250 for 12-and-a-half hours auditing which is usually spread out over several weeks. The church calls all fee donations, part of an exchange between the church and its parishioners, says Public Secretary Bill Osvath.

This exchange includes volunteering for the church in its many community programs like the Volunteer Ministers program and the Applied Scholastics program.

When I asked to see a booklet on a communications course, I was refused, told that they aren’t given away but purchased when someone signs up for the course. I guess it’s all part of the exchange philosophy. I tried to browse through, but couldn’t get any answers as to what students learn from it — better communication techniques was all I was told.

The founder of Scientology, L. Ron Hubbard puts much of the focus on understanding words in order to learn.

“The only reason a person gives up a study or becomes confused or unable to learn is because he [or] she has gone past a word that was not undersood,” Hubbard wrote.

Scientology is broader than the actual church. Osvath says that a member can be anyone who is a member of the church or a group that reads Scientology-related books, like Dianetics.

Osvath defines a Scientologist as one who makes better conditions in life using Scientology. One can be a Scientologist and practice other religions.

The word Scientology means the study of knowledge. Scientology recognizes that there is an ultimate reality, Supreme Being or force that transcends the here and now of the secular world. Through its drills and studies, it’s believed that one can find the truth for oneself. It is not interpreted as something to believe, but rather something to do.

I’ve had to do a lot of background research on my own, since I didn’t get any solid answers at the church. But I wanted to keep looking, so I checked out some of the free services offered on Sundays at 10 a.m. I went to two of them. There’s no signs leading to the clear-paned door, around the side of the building, on St. Mary Street, west of Yonge Street. The white-walled chapel could squish about 100 people and I stuck out — I assume people could tell I was new since I hear people greeting me with an enthusiastic “Good morning!”

I was told to not take notes during the group processing, which is another form of auditing — a time to think about how to deal with the problems in my life. The man that asked this sat in front of the podium, watching to make sure I obeyed. I wrote, with notebook on the chair next to me, trying to make my moving hand inconspicuous. Still, I could feel his eyes on me, as I looked straight ahead.

A dark brown sculpture of L. Ron Hubbard’s face is positioned on a pedestal, behind the minister’s podium. He’s looking up, with his mouth open. The Scientology cross is on the wall behind it. I sat in the eighth row with about 20 other people scattered in the pews. A choir of three men in blue robes sing along to Hubbard’s The Joy of Creating — a compilation of positive-sounding music.

At both sessions, the female ministers spent the first 15 minutes reading the Creed of Scientology, an article by Hubbard titled “Personal Integrity,” and a sermon.

At the first session, the sermon was called, “Times must Change,” an essay by Hubbard. The second session’s sermon was called “What is the Basic Mystery?”

The next 45 minutes were dedicated to the group processing. The auditor-slash-minister started off by asking the group to “Get [in mind] some things that are not going to happen tomorrow.” We got a few seconds to think about this. The ideas kept flowing.

“Get some things people are not going to do to you tomorrow.” Later on, the minister said “let go of one thing, see if it stays there.”

Each person tried to answer these abstract ideas in his or her own mind. The only thing I could think of was that I knew that my mother will not hit me tomorrow.

We started to become aware of how we affect others, answering questions silently in our thoughts. “Think of methods that could produce an effect on the opposite sex.”

Then, “What effects do the opposite sex have on you?” The pattern continued.

“How did your mother produce an effect on your father?”

Then I heard a familiar question: “Who is the person you dislike the most?” Again, I found it hard to answer. “What effect did he/ she have on you?” and “How did you affect him or her?”

These exercises are meant to make people more aware of their surroundings, feelings and self. I may have begun to dig up answers about how I behave, but now the big unanswered questions repeats in my mind: Why? Now What? Was I supposed to take courses like Success through Communication? Taking courses or reading L. Ron Hubbard books to further educate myself is the only resolution given. I left the place with more questions than I came with. And I was still thinking about the celebrity spokespeople whose faces and decrees are often used in promoting Scientology. It was one of the reasons I wanted to check the church out.

Osvath speculated that celebrity membership in Scientology could be because of a lifestyle that causes them to seek answers about their lives. John Travolta, Jenna Elfman, Tom Cruise and Kristie Alley are just a few members of the church. But there are plenty of detractors who question celebrity motivations. Apart from urban legend and rumour, FactNet.org — a website that delves into cults and mind control methods — claims celebrity Scientologists are getting lucrative compensation for endorsing the religion.

In fact, Scientology has often been accused of being a cult, with mind-controlling tactics used to harpoon members into sticking with the church. Time magazine has called it a “Thriving cult of greed and power.”

There have been numerous court cases and legal battles regarding the religious philosophy’s attempts to keep anti-Scientology material off the Internet.

A former journalist in Adelaide, Australia, Alison Braund, was one of the many people who have been caught and arrested for trying to infiltrate the church.

My visit to the Church of Scientology was in early October. It’s now January and I’m still getting phone calls from members asking me to come to meetings. When I say no, they ask why but it seems they’re not listening to the answer. My phone keeps ringing.

Leave a Reply