By Deni Verklan

There was more than enough room for Jeremy Davidson to sneak into the next lane.

He was stopped at a red light in downtown Toronto, traffic wasn’t moving and neither was the cab that was slightly behind him in the next lane over.

So, like any driver trying to squeeze into congested Toronto traffic, Davidson took advantage and angled his car into the next lane.

That’s when the cabbie stepped on the gas, aiming right for the side of his vehicle. And there was no sign of him slowing down.

Davidson had only been an Uber driver for a couple of weeks. With no training other than a 10-minute video that instructed him to give water to his customers like a limousine driver, he did what most drivers would do: with no time to check where he was going, he jerked his vehicle back into his lane.

The cab screeched to a halt where his under-a-month-old 2016 Dodge Grand Caravan had once been. It would’ve hit his car if he hadn’t pulled away.

“Obviously I thought they were an idiot for doing it,” says the Ted Rogers School of Management class of 2014 graduate. “I do [feel guilty driving for Uber] in the sense that it takes over all these people’s jobs. But at the same time, I have to survive, too.”

Toronto taxis have been saying the same thing, protesting Uber’s presence in Toronto with numerous protests shutting down major streets this past year.

In October, Toronto City Council voted to update existing taxi and limousine laws to apply to Uber, which includes paying for proper licensing and brokerage fees.

But the battle between the two industries is an inherently unfair one — taxi drivers’ fixed metre charges aren’t able to compete with Uber’s lower prices.

Taxi drivers are forced to pay an average of $1,000 in annual-renewal fees on taxi plates, stickers and provincial plates; $40 for an annual criminal-record check; fees for a CPR refresher course; $950 in monthly car and insurance payments; and about $525 in monthly brokerage, depending on the driver’s dispatch company and the number of calls the driver buys from dispatch.

Although city council asked Uber to stop its services in the interim, the company — which launched its Toronto chapter in 2010 — continued to operate with more than 500,000 riders and at least 20,000 drivers in Toronto.

On Jan. 22, Uber released a statement saying it had been granted a brokerage license for all services except uberX (for which drivers use their own vehicles) — effectively eliminating the threat of one of the two charges laid against its drivers.

According to Uber’s website, partners spend an average of 10 hours driving per week — which a 2015 study by Princeton University cited as one of the most attractive characteristics of the ridesharing company for its drivers.

While no Canadian studies have analyzed the makeup of Uber’s drivers, the Princeton study found that seven per cent of Uber drivers in the United States are students.

These students were a large part of the 32 per cent of drivers who worked for Uber “while looking for a steady, full-time job” — like Davidson, who’s been primarily landscaping since graduation, with a brief stint as a security guard before studying Arabic for 8 months.

Working for Uber was a convenient decision that’s been helping him pay off $35,000 in student loans and $21,000 in car payments. He didn’t have to leave his house after landscaping for 12 hours to apply or have an interview — the only time he stepped into the Uber headquarters was to double check that there were no hidden fees.

Working for Uber was a convenient decision that’s been helping him pay off $35,000 in student loans

Sitting behind a computer in the Toronto offices on Adelaide Street East is Justin Valmores. At home in the modern glass and wood-panel swank of the HQ, Valmores works full-time as a community support representative.

He spends around 40 hours a week responding to emails about lost wallets and surcharges, while also juggling a full course load as a third-year RTA student.

“I don’t think I could have ever landed myself a better opportunity than with Uber,” says Valmores, who’s been working with the company for four months.

The success story of Uber has come up in several of his classes, Valmores says. Sitting in his advertising copywriting class, students discussed the creativity behind Uber’s elastic brand.

This is what Valmores characterizes as the difference between the (cheaper) uberX service, and (the more luxurious) UberBLACK.

The first time that Valmores used Uber, in fact, was with an UberBLACK.

It was April 2015, and Valmores was headed to the RTA program’s TARA awards with three friends. Standing at the corner of Victoria and Dundas streets, dressed in a tuxedo and with $20 of free Uber credit in his pocket, he embarked on his first car ride.

“The guy opened the had a bottle of water in the back, and I’m thinking, ‘Do I pay for this? Do I not? How does this work?’” he recalls.

The affordable luxury of the UberBLACK, combined with other services like the competitively-priced uberX, is what Valmores says defines the popularity of Uber in Toronto — especially for university students who “could use the extra dollars here and there.”

Davidson is a more recent addition to the Uber team, having started in December.

Since then, he’s made contacts in marketing by talking to a few customers. And, as Uber allows drivers to set their own schedules, Davidson says it makes applying for marketing jobs and scheduling interviews easier (though he’s working 30-40 hours per week). But those are largely the only positive aspects of Uber for him.

Although Uber says that drivers can make $20 an hour, Davidson says it’s only about $15 after deducting gas costs. The driver’s vehicle and insurance are also considered personal expenses.

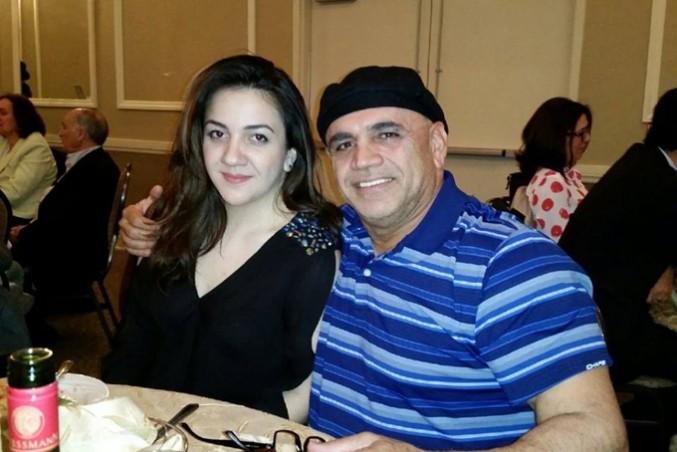

As his wife is studying on a full scholarship at the University of Toronto for a master’s degree in criminology, Davidson is the sole debtor and income earner for the newlywed couple.

To afford rent in their basement North York apartment, vehicle payments, insurance, gas and food, the 24-year-old needs to earn at least $2,500 per month.

But earning that “bare minimum” won’t be possible if Uber becomes regulated.

“They (Uber) have two advantages. One is that they’ve got a great product and the other is that they’re not following the same regulations that other companies are following,” says Ryerson business-ethics professor Chris MacDonald. “The fact that you’ve got a great product isn’t unfair — the fact that you’re keeping your costs low by not following the rules is characterized as not fair.”

Davidson says that if limousine and taxi licensing by-laws are applied to Uber, he would quit right away. “Unless they’re paying you to do this, it’s not worth it at all. It would take a week of you working just to pay for the commercial insurance,” he says.

Like many non-professional Uber drivers, Davidson uses his personal auto insurance to protect himself on the road. At $290 a month, it’s the cheapest insurance he can find as a 24-year-old male.

For third-year Ryerson sociology student Saba Mirsalari, the lack of insurance isn’t the only reason why she’s never taken an Uber — which she calls a regulation-free taxi service, even though the cheapprices are “tempting.” As the daughter of a taxi driver, she’s fundamentally against the idea.“It’s not just because, ‘Oh, my father’s a cab driver, I shouldn’t be doing this.’ It’s also a personal choice,” Mirsalari says. “For me safety is a huge deal. I know that when I’m in a licensed cab, whether that’s Beck Taxi, Crown Taxi, Co-Op or any other cab … that I’m going to be safe and I know that, God forbid, if anything ever were to happen to me in that cab, that company would have my back.”

Taxicabs have additional safety features for passengers that Uber does not. These include 17 days of training for drivers, the mandatory cab and driver information on the back of the car seat, a 24/7 call centre that ensures all drivers facing serious complaints receive additional training and appropriate disciplinary actions, and security cameras that are accessible to the Toronto Police Service.

But, for Mirsalari’s father, Jafar, those additional security measures aren’t enough for the drivers’ security.

One of his first brushes with danger was in 1989 when, at 3:15 a.m., two men opened the back door of his Chevrolet taxi as he was turning a corner at Yonge and Bloor streets.

With no power locks on the doors, Jafar had no choice but to take them to their dead-end street destination, when the man sitting directly behind him grabbed him by the neck as his partner tried to reach for his pockets.

Jafar managed to release himself, and the two men took off when they realized that Jafar was fighting back.

For Davidson, driving for Uber is much more exhausting than a 12-hour landscaping shift. Not only does he have the added pressure of driving to the customer’s liking to keep his rating at 4.66, but he’s also had to defend his religion to Islamophobic customers in his vehicle.

The smartphone app allows users to see exactly who and where their driver is, how long it will take for the vehicle to arrive and which vehicle the partner is driving (a detail that’s required and verified by Uber).

But it doesn’t allow the driver to save names of rude or abusive customers, which makes finding troublesome passengers difficult.

Davidson says that the most he can do is rate them.

It’s easy for passengers to receive a 5-star rating from the driver, unless they were a no-show or were abusive. For a driver, it all depends on the passenger’s mood and opinions.

One customer was particularly opinionated about Davidson’s kufi, a rounded cap often associated with Islam.

As Davidson drove him from East Richmond Hill to a house in the west end, the man ranted about how Davidson shouldn’t be wearing religious symbols in the workplace and how he agreed with Donald Trump’s views on Muslims.

His wife sat quietly in the back seat.

Although Davidson accidentally rated them five stars out of habit, then reported them at the end of the night, he got the last word.

“I told him, ‘This is my vehicle — if you don’t like it, you can get out right now.’”

Though Uber employees are told to be “level-headed” when engaging in Uber versus taxi debates (“They tell us, ‘Even though we work with Uber, we still need to take into consideration how they feel’”) Valmores says the popularity of Uber is natural after the lengthy monopoly of the taxi industry on Toronto transportation.

“It’s about time that we kind of keep up with technology … and use this as a way to, you know, better our services.”

But with a growing usership of Uber — which boasts safer conditions for drivers and customers — amongst young people, Jafar has lost about a quarter of his income.

Jafar has lost about a quarter of his income

His dispatch, Beck Taxi, receives almost 50 per cent less calls than in previous years, with wait times in between calls stretching to over an hour.

Back when he first started in the taxi industry 29 years ago, a slow day meant a 20 or 30-minute gap in calls.

Although his wife works full-time as a receptionist at a dental practice, Jafar finds himself driving downtown at 2 a.m. on weekends, and not going home until 3:30 a.m on other nights.

He does this to cover for slow Mondays and Tuesdays, pay off his $270,000 mortgage, pay into the RESP that funds his son and his daughter’s degrees, and for the line of credit paying for Mirsalari’s travel costs for her semester abroad in Singapore.

Some weeks, Jafar works up to 90 hours to cover his expenses. “[Mom and dad have] never made me think about student debt. They’ve been like, ‘No, this is our job. We’re your parents.’ In order to do that, I see the amount of time they both spend working,” Mirsalari says. “But the days that he works long hours, I can definitely see that he comes home really tired.”

Leave a Reply