By Renata D’Aliesio

It’s a desolate, grey November morning. The drizzle that has persisted for the past two hours begins to pour down with a vengeance. Pedestrians scurry for cover under store awnings as raindrops pelt the sidewalks, but the downpour isn’t strong enough to sway Kyle Rae’s jubilant mood. He stands in front of the Eaton Centre’s glass gate — the Yonge and Dundas entrance into Canada’s most visited shopping kingdom.

He cocks his head back to survey the mural he commissioned atop the Jewellery Exchange, two stores south of the World’s Biggest Jean Store on the southeast corner. Painters began to work on it three weeks ago after the Ontario Court of Appeal rejected a leave of appeal raised by property owners residing on the east side of Yonge. Jewellery Exchange is one of 12 properties the city will take possession of on Jan. 15, 1999.

The mural is not halfway completed yet, but the city is eager to show off anything to do with their prized project — the Yonge-Dundas redevelopment. “The leave of appeal was the last major hurdle we had to overcome and now it’s time to make sure everyone knows about the development,” says Rae. He and the mayor’s office arranged for a swarm of local media to swoop down on the intersection for a lunch-hour press conference. “Mel [Lastman] and I are going up on the scaffold,” Rae tells a reporter who arrives early for the sideshow act. As key figures behind the project begin to arrive, Rae makes his way across the street to greet them.

The corner of Yonge and Dundas is at the heart of Rae’s ward, the bustling epicenter of Toronto. His constituency is bordered by social housing projects to the east, the business district to the west and, to the north, Toronto’s gay district — Church and Wellesley. Rae’s originally got into politics because he was an activist, fighting within the system for those with few voices — minorities, the homeless and especially the gay and lesbian community. So when the became the cheerleader for the Yonge-Dundas redevelopment, he wasn’t the only one surprised.

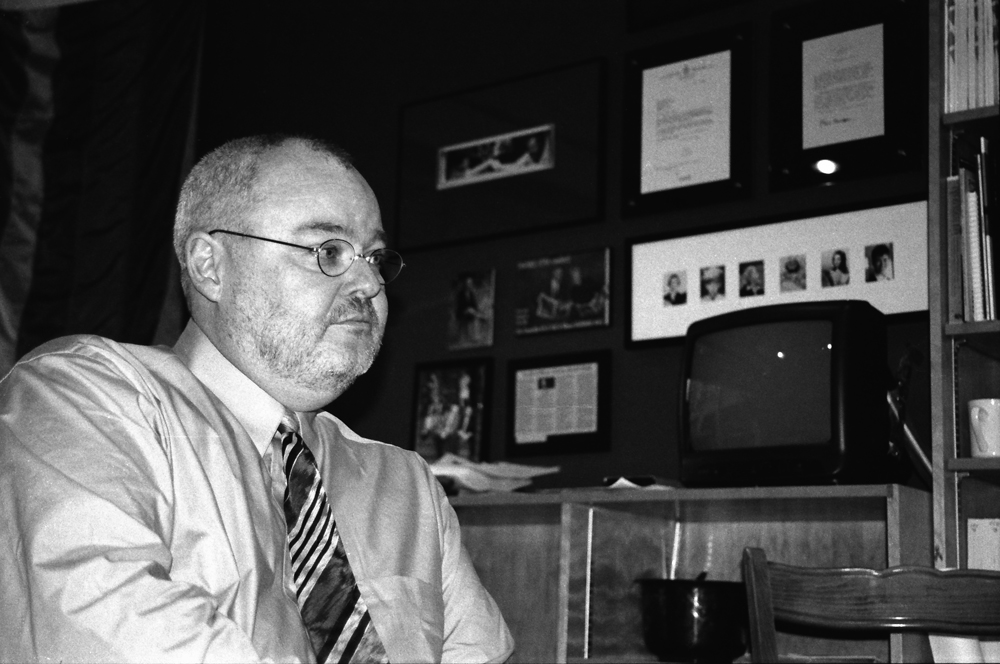

Rae isn’t the person most would have chosen to play the lead role in the city’s downtown redevelopment story. Toronto’s first openly gay councilor is known for being an activist, rather than taking a leading role in pushing for a business development. And although Rae didn’t’ come up with the concept, eh is the one who sold vision to a city council wary of property expropriation in the wake of recent development disasters. He has become the Yonge-Dundas poster boy, making all the necessary appearances and calls to promote the project.

But Rae is quick to distribute the acclaim appropriately: to the Yonge Street Business and Residents Association (YSBRA), who initiated redevelopment talks; to project director Ron Soskolne, who provided the vision and plans; and to city council, who approved the proposal and funding. But history generally doesn’t remember a myriad of key characters. It looks for a leader, on whose story can be spun into a memorable and engaging tale. Rae’s character fits the bill — small-time politician makes it to the big show.

Posters advocating gay and lesbian rights adorn the walls of Rae’s second-floor City Hall office. It’s recently been renovated and given a fresh coat of forest green paint, part of $6.6 million being spent to build and renovate offices for the larger amalgamated council. As I wait for Rae to arrive for our interview, a poster taped to the side of a beige metal shelf used to store city documents and proposals draws my attention. It’s a poster promoting the academy-award winning film The Times of Harvey Milk.

The film recounts the life of Milk, who in 1977 became the first openly gay person in san Francisco, California, to win a seat on city council. His victory came at time when a “save our children” campaign was being mounted many U.S. states including California. His election angered anti-gay supporters including city supervisor Danny White. On Nov. 27, 1978, 11 months after Milk’s election into office, he and San Francisco mayor George Moscone were shot to death by White in City Hall. White was convicted of two counts of voluntary manslaughter and sent to prison for seven years and eight months. He was paroled after six years in prison and committed suicide shortly after.

The poster reminds Rae that the gay ad lesbian struggle isn’t over. When the Oakville native first moved to downtown Toronto 17 years ago, he stayed away from the less gay-friendly downtown neighbourhoods for fear of being beaten up because he was gay. Rae had just completed a masters program in England in medieval history. When he returned in 1981, he found a job working in the University of Toronto’s Robarts library. While at U of T, he completed a doctorate in library science.

Rae never aspired to be a politician. It wasn’t until 1986, when he became executive director of Toronto’s largest gay and lesbian centre — the 519 Church Street Community Centre — that he begat the idea of entering city politics. (Rae became actively involved in the centre soon after his return to Toronto, and helped organize the city’s first gay pride parade 18 years ago).

The idea gained substance in 1989 when Rae fought to get the city issue a proclamation recognizing Lesbian and Gay Pride Day. City council first approved the proclamation of the event, but reversed its decision two weeks later. Rae field an emergency application to the Supreme Court of Ontario, asking it to uphold the Ontario Human Rights Code to get city council to proclaim the day in time for the community’s ninth-annual gay pride parade.

The proclamation never came that year. The reluctance of city council to acknowledge gay and lesbian rights angered and frustrated Rae. Change was needed, but enacting it from the outside was proving near impossible. In 1991, Rae ran for and won his first downtown council seat.

It’s a bright, warm Jun day in 1993. The media assembles at City hall for a historical flag-raising. Mayor June Rowlands is absent, but Rae is more than happy to fill in for her this day. In only his second year as councilor, Rae helps persuade council to approve a proclamation recognizing Lesbian and Gay Pride Day. In minutes he will take that recognition one step further, when a rainbow flag — the multicoloured symbol of the lesbian and gay community’s diversity — is raised for the first time at City Hall.

As a councilor, Rae has been able to champion the gay and lesbian cause more effectively. Gays and lesbians from outside his downtown constituency know he’s the person to call when they feel their rights have been infringed upon. But Rae isn’t just a gay-rights politician. In 1993, as head of council’s personnel committee, Rae advocated changes to the Toronto Fire Department’s hiring policy to allow more women and minorities into a department that’s almost exclusively made up of white males. The proposal was vehemently opposed by many councillors including council veteran Tom Jakobek, who vowed to fight to maintain the hiring system in which the highest-scoring candidates were selected. But a resolution appears near. Less than one month ago, an agreement between the city and the Ontario Human Rights Commission was proposed to councillors in a confidential memo. If ratified by council, the agreement will force the fire department to recruit more minorities, aboriginals, women and disabled persons. Rae hopes the agreement will put employment equity concerns to rest.

So how does a man who’s been termed a New Democrat social activist by some councillors become the champion of the biggest economic and land development to hit downtown since the Eaton Centre in 1976? It is a metamorphosis that took Rae, his friends and supporters by surprise.

“I was thrown off,” Rae says. “I am the fag from Church-Wellesley. That’s what I am. My background is doing development work in neighbourhoods. Working on tenants’ issues, homeless issues, gay and lesbian issues, human rights issues, not developers, but it’s part of the terrain. There is not a choice but to get involved. If you don’t get involved then you end up with development that people will hate.”

It was in 1993 when Rae began hearing serious grumblings from Yonge Street businessmen like restaurants Arron Barberian and Bob Sniderman. One summer night the two stood near Yonge and Dundas and surveyed the dark, empty sidewalks. It was a far different scene than the one played out during the intersection’s heyday in the 1960s. That was at time when the sidewalks bustled with tourists, shoppers and movie-goers. Yonge and Dundas was a people place and Canada’s most-visited retail shopping strip.

Barberian and Sniderman decided something had to be done to bring the bustle and the people back to the strip. The downturn and decay that began with the opening of the Eaton Centre in 1976had to be stopped.

The Eaton Centre was hailed as a triumph — a behemoth tourist attraction that was going to draw millions of visitors to the downtown core A new wave of retailing had arrived and an economic spillover was anticipatd for the street. Property owners on the east side of Yonge between Queen and College Streets were waiting to reap the economic benefits. They signed their tenants to short-term and open leases, waiting for big businesses to come knocking. But instead, the Eaton Centre acted as a vacuum, sucking the successful businesses in.

Today, 26 dollar stores litter the strip between Queen and College. In between them is a smattering of sex shops, low-end clothing and shoe stores and a couple of fast food joints. It isn’t the Yonge Street city council or planners envisioned 22 years ago. The city didn’t even bother installing street lamps because it thought an electric mix of businesses would illuminate the sidewalks at night. Instead drug dealers and the homeless occupy the dark alcoves and unlit alleys.

When it comes to laying blame for Yonge and Dundas’ decay, Rae’s sentiments have been echoed by mayor Mel Lastman. They place the blame squarely on the shoulders of the property owners. They say the owner’s disinterest and lack of pride has led to the decay of their buildings. And jealousy has left them isolated and prevented them from joining together to improve their state.

“When people come up the escalators in the Eastern Centre, what do they see? Windows on Yonge. That’s a dump. The World’s Biggest Jean store. That’s tacky. The whole area is a disgrace. There’s nothing there to draw people onto the street,” Rae says.

The Eaton Centre is often singled out as the second culprit — the development that gobbled up land on the west side of Y onge and turned its back on the east. But while Rae is quick to point fingers away fromt eh city, it is just as much responsible for Yonge Street’s decay because for the past two decades, it has failed to do anything substantial to revitalize the core. “Something should have been done years ago,” said Lastman at a press conference last Tuesday. “We [should] have done something.”

A 1979 consultant report for the city stated: “Yonge St. (sic) doesn’t have a single problem. Rather it has a network of problems, many of which have been years in the making. Yonge St. is tired and dated. Its pulse is weakening. It needs surgery.” Nineteen years later, the city, led by Rae, is ready to enter the operating room and is pushing to begin surgery as soon as possible.

Rae, like many downtown councillors before him, recognized Yonge and Dundas was in need of significant repair. But there was no way he could bring about the necessary change required alone. The community had to step forward. More specifically, it was up to the business owners to join forces and initiate a plan to stop and reverse the decay. But this didn’t’ mean Rae sat back and waited for things to happen. He took action almost immediately after Barberian and Sniderman expressed their concerns in 1993. He became a mediator between Yonge and Dundas businesses, encouraging them to work together, from the Eaton Centre, to the Delta Chelsea Inn, to the jewelry vendor at Yonge and Gould Streets. The mediation and schmoozing paid off. In March, 1995, the Yonge Street Business and Residents Association (YSBRA) was formed.

It was after the creation of the YSBRA when the idea of drastic redevelopment for Yonge and Dundas began to blossom, and quickly. On June 24, 1996, a sub-group of the Yonge Street Regeneration Steering Committee was formed with three members: David Bednar, then-chair of YSBRA, Soskolne, who was hired by YSBRA as a consultant and became director of the Yonge-Dundas redevelopment, and Rae. The purpose of the sub-group, which worked in secrecy, was to investigate and develop a concept that would rejuvenate Yonge and Dundas. This took the group only five months.

In December, 1996, a major redevelopment, including a 30-screen cinema, a public square and an underground parking garage, was announced for the first time to city council. Five months later, the search for a tenant and developer of the cinema was completed and council approved AMC Entertainment International Inc., a U.S.-based theatre entertainment company, as the tenant, and PenEquity Management Corp. as the developer. If the Ontario Municipal Board hearings hadn’t dragged on until June, 1998, construction would have already begun. As it stands now, on Jan. 15, 1999, a little more than two years after the $90 million project was publicly announced, the city will take possession of 12 properties and turn part of them over to PenEquity to begin construction on a 30-screen cinema.

Two years — to pass a project YSBRA’s Barberian says would normally have taken about 10. Two years — for the city to complete all the investigation and consultation it needed to pass the biggest land development downtown has seen since the Eaton Centre. Two years — for the city to make sure it would avoid repeating its Ataratiri and Centara development disasters.

Ataratiri and Centara were the two biggest public spending disasters in the city’s history. Ataratiri, an 80-acre industrial wasteland on the eastern fringes of downtown, was a development plan dreamed up by the city and province in 1988 to create 7,000 low cost housing units. It was originally billed as a break-even venture. Approximately $260 million went toward expropriating 256 parcels of land near the Don River. But before taxpayers’ dollars were committed to the project, neither the city nor the province thought of testing the soil in the area. It turned out that much of the land was contaminated with toxic chemicals. Estimated cleanup costs ballooned to $180 million from $30 million. Another problem discovered after expropriation was that the land was sitting in the middle of a flood plain. Floodproofing the area would cost another $60 million.

The soaring cleanup and floodproofing costs forced the province — which had relieved the city of its stake in the project — to abandon Ataratiri in 1991. So far, provincial taxpayers are on the hook for at least $300 million — $260 million for expropriating the properties and $40 million spent on interest and other wind-down costs. Seven years after the project was axed, a grim, polluted 80-acre industrial wasteland remains.

Two years after the city jumped hastily into the Ataratiri deal, it did so again with the Centara project. In the fall of 1990, Centara Corp., a condominium developer came to council with an offer. The project called on the city to join forces with Centara to build 1,400 housing units, roughly half of which were to be social housing; the remainder would be sold at market value. Under the plan, the city would bring to the partnership the 11-storey Sears warehouse building it owned on the southeast corner of Mutual and Church Streets, plus about $15 million in working capital. Centara would bring $15 million and four parcels of land in the Dundas and Mutual streets area.

Less than six months after the Centara proposal was announced, the deal was gathering momentum at City hall. But three councillors, unhappy with the vague assurances from housing officials, called for a moratorium. A subsequent report found that Centara was bringing to the partnership two acres of land burdened with a $54 million debt that would first have to be cleared before the city could turn a profit. An agreement was hammered out that reduced the city’s risk to $30 million.

Another problem was the condo market was in a slump and there were no guarantees it would recover any time soon. But despite the apparent risks, city council, in the spring of 1991, voted 9-7 in favour of the deal. Two years later, after only one modest non-profit housing project had been built, the city finally decided to pull out of Centara. The city lost about $10 million in the ill-fated deal. In 1996, the city sold the Sears building for $4.6 million, almost $30 million less than its peak market value.

Rae and city planners knew full well of the background behind the failed Ataratiri and Centara developments. KPMG, a consulting firm hired to assess the Yonge-Dundas redevelopment, advised the city to proceed with land acquisition in an expeditious manner, so as to avoid another Ataratiri. In a February, 1997 letter written by KPMG consultant Jeffrey Seider to Gary Wright, the city’s manager of urban development, Seider said: “If the community improvement process and land acquisition process are spread out over a long period of time there is a risk that the market opportunity will be lost or have adversely changed. Running concurrent processes and accelerating the time line will contribute to avoiding the experience, such as Ataratiri, where an extended approval and acquisition process led to the missing of important market opportunities. Consequently, any initiative which will enhance the city’s ability to reduce or control risk, such as approval for the early acquisition of land, should be supported.”

Soskolne also advised the city to avoid delays to the project because there were several key retailers, restaurateurs and entertainment operators who were looking to locate downtown. In a letter from Soskolne to Wright, dated Feb. 25, 1997, Soskolne outlined his fear that if the approval process was drawn out, businesses would choose to locate at the several competing locations instead (Bloor Street, Queen Street West, the entertainment district and the railway lands).

“Yonge Street has a unique opportunity to attract a critical mass of these tenants whose presence there would be the necessary catalyst for change,” wrote Soskolne. “Unless the project is implemented within the targeted schedule it is likely that a new wave of speculation will be rekindled by the general upturn which is beginning to occur in Toronto real estate, and the opportunity will be substantially lost.”

Rae heeded Seider’s and Soskolne’s warnings. When Soskolne began talks with AMC in November, 1996 about developing a multiplex cinema atop Ryerson’s parking garage at Victoria and Dundas Streets, Rae didn’t interfere, even though the Yonge-Dundas redevelopment hadn’t been brought before city council yet. In a letter to Wright, dated Nov. 28, 1996, Soskolne suggest the city skip the open bidding process for land developers, and instead “assist AMC to put together the required land” with PenEquity, AMC’s preferred developer. Four days later, AMC sent out a formal offer to lease to PenEquity for a 20 to 24-screen theatre to be built atop Ryerson’s parking garage. Eight days after the offer to lease was sent out, city council heard about the Yonge-Dundas redevelopment proposal for the first time. In February, the council announced that all land was open to developers to submit a request for qualifications (RFQ) — a process to select a qualified developer — but that parcel A, the site of the cinema, may already have been taken.

In a memo dated March 20, 1997, form Cho Khong, who was then working in the city’s finance department, to Wright, Khong expressed concern of the “premature timing” of the PenEquity proposal. “The knowledge gained in preparing the proposal would represent an advantage over other proponents involved in the RFQ. It would put the RFQ process in question,” Khong wrote.

But Rae dismisses claims that the AMC-PenEquity deal was anything less than fair or transparent. He says in order to sell the Yonge-Dundas redevelopment proposal to city council, councillors had to be assured that an interested and qualified developer and tenant would be waiting in the wings. He says the Ataratiri or Centara in any way. After those two city-developments debacles, council would never approve an expropriation deal gain without strong assurances all risks to the city had been minimized. That’s why soon after the Ontario Municipal Board approved the Yonge-Dundas redevelopment project, the city council’s strategic policies and priorities committee released a report outlining recommendations for the city to minimize its risk in the development deal. The city hopes to spend a total of $14.4 million to built a public square and the underground parking garage. IF the costs to acquire the land escalate, the city has options that will bring in up to $60 million in extra revenue over two decades, which include naming rights, a levy and through tax revenue.

Rae gets very animated when he talks about the Yonge-Dundas redevelopment. His desk is cluttered with Yonge and Dundas maps. He believes the project will help bring life and warmth back to the city. “The downtown is the heart of this city. If it dies on the vine, the city will go that way.”

Close to the same sentiments were said more than 40 years ago, when then-mayor Nathan Phillips proposed building City Hall and a public square at Queen and Bay streets. More than any other piece of architecture in Toronto at the time, City hall marked the city’s entry into the modern age. The development helped revitalize the downtown core. It gave people a reason to travel downtown once again. Businesses that had been in slow decline for years had customers bustling through their shops.

Though the development is admired today, getting the proposal wasn’t as easy for Phillips as it was for Rae. Work on the project began in 1955, a full 10 years before City hall officially opened. The proposal was almost thwarted when a plebiscite rejected it in 1955. But Phillips refused to let the development die and succeeded in convincing council and residents to accept a competition to design a modern city hall. About 520 submissions were received from 42 countries. By the time the architect was chosen in 1958, it was among the most famous unbuilt structures in North America. Though the project took four years to build and projected costs rocketed to $31 million from $7 million, when it was completed, it put Toronto no the list of most respected cities in the world.

Just as City Hall — which is undergoing renovations — reversed the decay of the downtown core in the 1960s, Rae hopes the Yonge-Dundas redevelopment will do the same. After construction is finished in the year 2000, no more major development by the city is planned for the area. What Rae expects will happen is the redevelopment will act as a catalyst of change north and south of the intersection. “Yonge and Dundas is the heart. It’s like when you throw a pebble and it ripples out. The pebble gets dropped at Yonge and Dundas and it will ripple from there,” Rae says.

And it’s already spreading. “You already have the pebble rippling. The Hudson Bay Outfitters is a ripple, the Eaton Centre doing their new façade down Yonge street is a ripple. The Gap wouldn’t have gone in there if there wasn’t that pebble dropped.”

The Yonge-Dundas redevelopment is about attracting a new class of business and cliental to the downtown core. And that means pushing the social problems — namely the homeless — outside the business zone.

Backing a plan to silence the voices of the weak wasn’t something people would have associated with downtown councilor a few years ago. The social activist turned politician fought to have those types of voices heard. But these are the kind of voices that will not be welcomed by the new, bigger businesses on the Yonge strip.

Following the closing of the Out of the Cold program at the Salvation Army this past spring, Rae said: “Operating a hostel in the middle of a tourist area is incompatible. People are intimidated and terrified by [the homeless].”

While Rae admits hostels are a short-term solution to the homeless problem, he plans to push for the opening of more in the downtown area. It’s his way of giving the homeless, who will no longer be welcomed on Yonge, a home.

Rae laughs bashfully when asked if this development is going to be his legacy — the one project, decades later, that history will connect him with. “Members of council have said, ‘Kyle this is important, you did this, people will remember,’ and it’s nice to hear that, but it’s not there yet,” he says.

Across the Eaton Centre out Lick’s, Kyle Rae, Arron Barberian and Bob Sniderman greet each other with smiles and handshakes. “It rains every time we come here,” says Barberian. “It rained that day we went for a walk.” That walk on a chilly, rainy autumn evening in 1995, when Barberian and Sniderman took then-mayor Barbara Hall, Rae and other area councillors on a tour of Yonge, helped prove to Rae the YSBRA was serious about fixing Yonge and Dundas. It was at that point Rae vowed the city would take a stake in the street and he would lead the charge.

Mayor Mel Lastman arrives about a half-hour late to the press conference. The media surge toward him. Words has gotten out that Lastman won’t be climbing the scaffold with Rae.

“So why aren’t you going up?” asks one reporter.

“It’s his [Rae’s] deal. He’s the guy who put this all together. I felt I should give it up to him,” responds Lastman.

Rae climbs onto the scaffold from a ladder, but all cameras remain focused on Lastman, who’s moved the crowd to the Eaton Centre. A photographer asks Lastman if he can click his heels while holding his umbrella. Lastman jumps in the air and clicks his heels together successfully. Flashes briefly light the grey November sky.

Rae has been standing on the scaffold for more than 10 minutes. Only one photographer has showed any interest in his appearance next to the mural publicizing a public square that will be built by the city as part of the Yonge-Dundas redevelopment. Lastman finally turns around and acknowledges Rae with a wave. Rae eagerly waves back, but Lastman has already turned away to answer another media request. They want to see him click his heels again. Rae comes down from the scaffold. As he takes off his safety-harness, I ask him if losing the media battle to Lastman bothers him.

“That’s Mel. Competing with Mel for attention is like competing with a newborn baby. You’re never going to win.”

1 Pingback