By Jonah Brunet

I’m in line at the grocery store, waiting on an elderly woman struggling to recall the PIN on her credit card. If it weren’t for the card, she’d be the kind who counted out her change, nickels at a time, on the stainless steel checkout — but it’s 2016, so here we are.

I don’t mean to seem irritable, and typically I’m not. But right now, I’m starving. A National Geographic on the checkout newsstand reads: “Superfoods” in big, orange caps and then, below, “Eat Your Way to Health and Longevity.” My eyes drift from the magazine stand across the black rubber conveyor belt, surveying my selections: one-dollar pasta, one-dollar canned sauce, 30-cent instant noodles (x4), beans, tuna, mushroom soup. Most of it canned, most of it bright, gaudy No-Name yellow. Not a fresh fruit or vegetable in sight. What am I eating my way to?

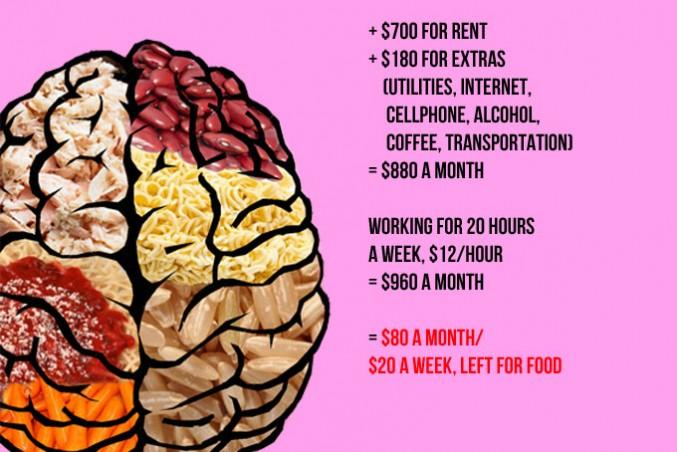

The idea was to try to eat for a week on $20. My editor and I did the math: assuming a post-secondary student works 20 hours a week, makes $12 an hour, pays $700 a month for rent, $50 for utilities, $30 for internet, $30 for his phone bill and averages $70 a month for incidentals such as travel, toiletries and alcohol, this is what’s left. It’s not a perfect representation. Notice the convenient absence of tuition, the single largest expense in a university student’s life. Many opt to work more than 20 hours a week to make ends meet, while others pay less rent by living at home, or piling into shabby apartments with multiple roommates. But the common theme here is that few of us have much to spare when it comes to feeding ourselves.

In 2014, the Good Food Centre released The Hunger Report, a demographic breakdown of those using Ryerson’s campus food bank and a frank assessment of how equipped it is to help them. “Demand is so high for the service that we cannot keep our shelves full for more than two days out of the week,” it reads. And two years later, not much has changed. While the Centre receives fresh produce and dairy products weekly, these are first to go, leaving the remaining students with the same kinds of canned, nutritionally questionable options on my shopping list.

The idea was to show how difficult it can be to survive on the amount our “average” student could afford to spend. Recognizing the financially precarious state of many students, the Ontario government recently announced the consolidation of several student benefit programs into the singular Ontario Student Grant. Government spending on post-secondary tuition is certainly desirable (although the province isn’t actually planning to spend any more than it currently does), but so is having somewhere to live, being able to access public transit, and getting enough to eat. There are many more costs to the university experience than just tuition, and even a basic necessity like food is not immune to compromise as students struggle with what’s often their first — and most extreme — exercise in personal budgeting.

And the idea, as early as day two, is beginning to seem bad. Whichever way you stretch it, $2.86 a day isn’t enough to get everything your body needs. In some ways, the first few days are the hardest. My stomach has yet to shrink in response to my new bargain diet, so I’m constantly hungry — especially here, staring at superfoods in line at the grocery store. And, while I have interviews scheduled with nutritionists and food experts later in the week, I’m going into this project essentially clueless.

Grocery shopping on the lowest possible budget is a task riddled with traps. According to nutritionists, many of the least expensive food options are ones people ought to avoid: things like boxed mac ‘n cheese, bags of white pasta and, worst (and cheapest) of all, instant ramen noodles.

“People want to buy foods that are going to give them a sense of immediate pleasure,” says Rena Mendelson, Ryerson professor and former director of the school of nutrition. “I think that’s a trap people often fall into.”

At around 30 cents per package, instant noodles are the discount epitome of immediate pleasure — followed immediately by stomach pains and a palpable feeling of shame from your body telling you you’ve essentially just eaten garbage. They’re high in sodium, carbs and fat, and devoid of helpful nutrients. If that’s not enough, a 2014 Journal of Nutrition study linked regular consumption of instant noodles to an increased risk of heart disease and stroke. And, largely because of the preservatives they’re laced with, instant noodles wreak havoc on your intestinal tract during digestion. In 2011, researchers using a tiny, ingestible camera noted the convulsions a person’s body goes through attempting to break the noodles down, which could explain why, 20 minutes after each bowl during the first three days of my diet, I feel like someone punched me in the gut.

While smart parents or high school programs will teach kids to cook, we’re rarely taught how to be poor

But even the less notoriously awful low-cost options are still problematic. The cheapest bag of pasta in most grocery stores is around a dollar and good for four or five meals. Combine it with the cheapest canned sauce and, at around 40 cents a serving, it seemed to me like the way to go. The taste is somewhere between not great and okay — a bit like tomatoes, garlic and basil; mostly like the inside of a tin can. But white pasta is almost as heavily processed as instant noodles, and has the same near-total lack of nutritional value. Rather than giving me energy, each meal left me bloated and tired.

Many of you reading this are likely smarter than me and wouldn’t have fallen into the same bargain pitfalls. When I thought protein, I thought canned tuna, canned beans and hot dogs. It never occurred to me that brown bread would fill me up more than white, or whole grain pasta as opposed to bleached. But I’m a child of my environment — a white, suburban, middle-class, all-around-unremarkable young man who had everything unquestioningly provided for him until the day he moved out. And I’m not the only one.

While smart parents or high school programs will teach kids to cook, we’re rarely taught how to be poor. My middle-school home economics class, cancelled a year later and replaced with a course in English literature, was more home than economics (one memorable lesson was on how to use a broom). And even students accustomed to cooking at home likely don’t consider the price tag attached to each ingredient and what they might do if, one gloomy day years down the line, their options became severely limited.

By the midway point of the week, I needed a change of strategy. I blew half my budget on garbage, and resolve to not do the same with my remaining $10. I call Mendelson for advice, who warns me that even the best-informed attempt to eat for less than $3 a day is essentially doomed.

“You’re looking for energy,” she says. “And that’s where you’re going to have a problem. You’ll be fatigued, mainly because of the monotony of the diet. When things are not appealing, you’re not tempted to eat that much, and that creates an issue. Your intake will be diminished because of the boredom. That’s going to be the biggest challenge.”

“Oh, I know,” I reply. I can feel it. Our interview is at 10 a.m. and, after about a dozen alarm/wake-up/snooze-button/fall-back-to-sleep cycles, I’m still barely awake.

“You’ll be fatigued, mainly because of the monotony of the diet. When things are not appealing, you’re not tempted to eat that much”

To make my revised list, I consult with Mendelson as well as Ciara Foy, an upbeat, downtown-Toronto nutritionist whose receptionist answers the phone with: “How can I make you smile today?”

“Your body has no clue what a calorie is,” she tells me. “It only knows if it has the right vitamins, minerals and phytochemicals to make your cells properly. So, with every food, you have to look at how nutrient-dense it is, because that’s its value.” She goes on to recommend I become vegan.

My revised shopping list is much shorter. One meal, cooked in bulk — a dietary Hail Mary to get me to the end of the week. Brown rice at 40 cents per 100 grams, dried lentils at 33 cents, dried beans at 30 cents and, for flavour, powdered chicken soup base, carrots and onions. It takes hours to soak the lentils and beans back to an edible state, at which point I throw them in a large pot with onions, carrots, water and soup mix. The rice gets cooked nearly all the way in a separate pot, then dumped in the soup, and the whole thing gets simmered until it thickens into a mash the consistency of oatmeal. It looks like puke, tastes like chicken and, loaded with protein for under 50 cents per serving, it’s the perfect dirt-cheap survival meal.

But then, tomorrow, it’s only okay — and the next day I’m absolutely sick of it. The monotony reaches a fever pitch and, by the last day of the week, I’d sooner starve my way to the finish line than eat another bite of mash. Healthy as it may be, the plainness becomes too much to handle, three meals a day, for long. Many people will tell you variety is the spice of life, but also: spices.

“People have a need to treat themselves under conditions of despair,” Mendelson told me, and delicious, flavourful food is the most common way people do this. It’s one of the main things, up there with love and music, that makes life worthwhile. And when it becomes restricted, not only does the body suffer a lack of nutrition, the mind suffers a lack of pleasure.

Though my true personal financial situation is far from perfect, it does allow me to eat food I actually like. But by the end of the week, I feel like I understand — like I’ve caught a glimpse of something dark that thousands of people, particularly students, are forced to live with every day. It is certainly possible to feed yourself, however badly, for $20 a week — but no one should be forced to, week after week, without access to help.

“Many of the students we see on a weekly basis are exhausted,” reads the Good Food Centre’s Hunger Report. “Weighed down by the intersecting stress of their course loads, personal obligations and financial worries, many students come to us as their last resort … We simply cannot provide the level and quality of food we know every hungry student deserves.”

Leave a Reply