By Laura Woodward

If you’re a student who buys your textbooks used, soon you won’t have that choice.

As textbook publishers shift their products from print to digital the resale market is slowly dying, as students can only buy digital products new.

Digital products are sold via access codes, a set of digits used to unlock an electronic textbook. But those access codes can only be used once, as they expire at the end of the course.

Ethan Senack, lead author of Access Denied, a research study on access codes, says the reason textbook publishers are going digital is to eliminate the used textbook market.

“No matter how bad prices got, students always had the ability to cut costs if they needed to, whether it’s sharing with a friend, borrowing from the library, buying used or even just opting out of buying a textbook entirely,” Senack says.

“But unfortunately we’ve gotten to a place where these alternatives have made the print textbook market unsustainable for publishers. They’ve had to find a business model that puts a stop to all of that competition. Through access codes, they found it.”

The textbook industry functions like the pharmaceutical industry. Pharmaceutical companies charm doctors into buying their drugs to prescribe to patients. Similarly, textbook publishers convince professors to assign their newest-edition-textbook, or access code with fancy features (like practice quizzes), to students.

Since 2006, the cost of a college textbook increased by 73 per cent and since 1977, the cost increased 1041 per cent, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In 2014, 45 per cent of McGraw-Hill’s sales were digital products.

Publishing companies are free to price their products however they choose, without any fear of market repercussions, since the student consumer has no purchase choice.

“At the end of the day, I can’t make back any money back from digital books.”

Dan Garcia, a second-year business student says, “it’s convenient not to carry heavy textbooks around campus, and access codes are cheaper, but I always think of the money I can save by selling my textbook later.”

Garcia sells and buys used textbooks through Facebook groups, Kijiji and the Ryerson used bookstore. There are currently 14,151 members in the Used Ryerson Textbook Facebook group.

“At the end of the day, I can’t make back any money back from digital books. So it might be cheaper up front, but not long term,” Garcia says.

At Ryerson’s bookstore, access codes range from $31 to $140. If a student desires a hard copy, there is the option to add a loose-leaf printout for an additional price.

Some publishing companies have chosen to bundle their digital and hard copy products together, forcing students to buy both.

But universities are cracking down on the bundling scheme and have created guidelines for textbook stores to sell learning products separately.

David Swail is the executive director at Canadian Publishers’ Council, an association that represents the major textbook publishers.

Swail is also the former CEO of leading publisher McGraw-Hill Ryerson. He admits that publishing companies do try and eliminate the used textbook market, as seen with new editions.

“Everyone questions what’s so different about a 13th edition textbook, versus the 12th edition, ‘Aren’t you just trying to squeeze used textbooks out of the market and force us to pay more?’ The honest truth is that there’s some truth to that. As a publisher, you want to have a new product sold,” Swail says.

And the new products are digital.

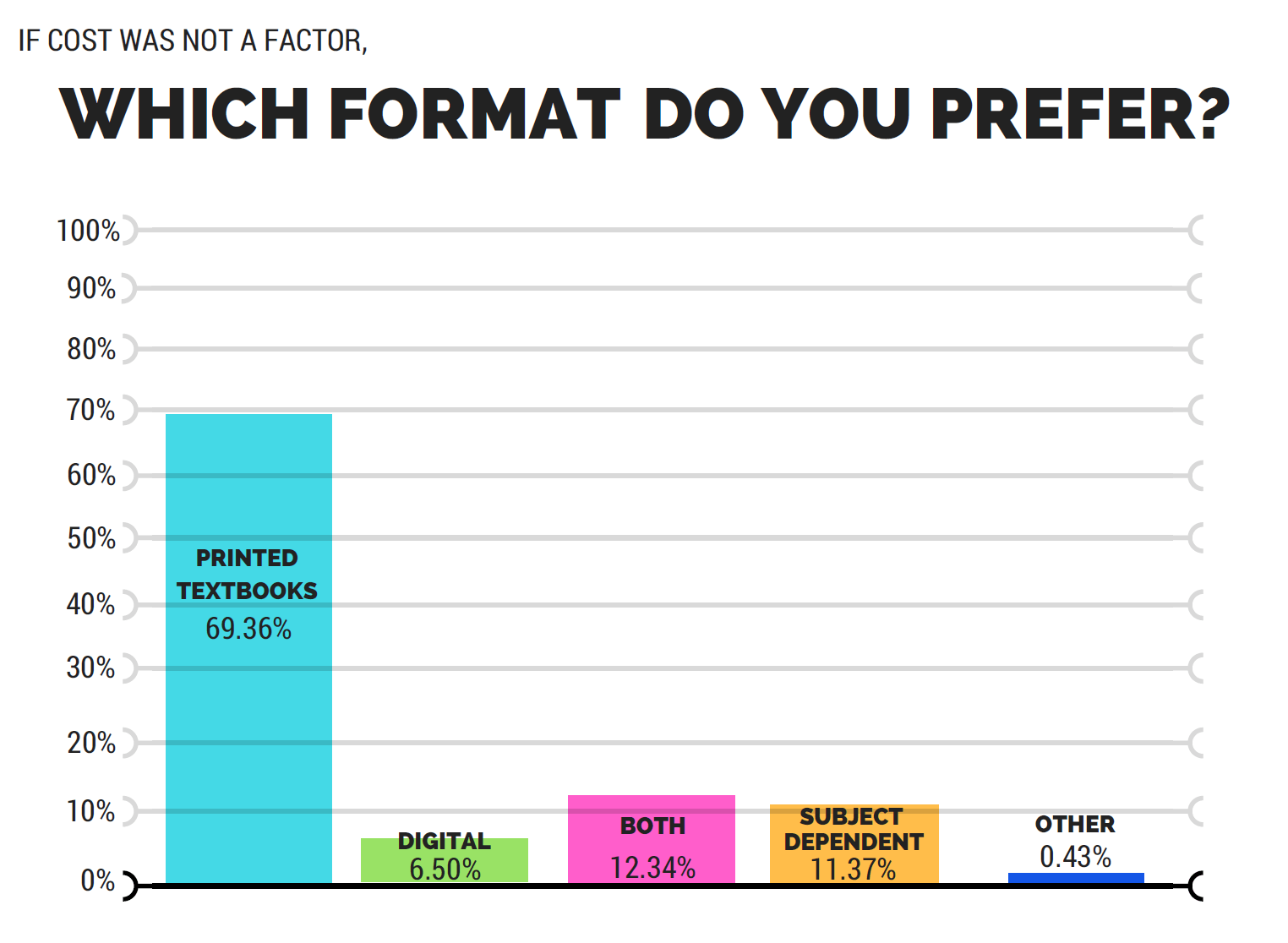

Data: University of Waterloo Book Store

“Digital is more engaging and interesting… That’s hard to [achieve] with a used text- book. When we say digital, we’re not talking e-books or a PDF replication of a textbook. We’re talking online resources that are responsive and adaptive to a student’s needs,” Swail says, referring to features like quizzes embedded in the text, ensuring students don’t move onto the next chapter until they’re ready.

Because of the quiz component of these digital products, the option to opt-out of buying an access code and just use a textbook also comes at a cost—failing the course.

McGraw-Hill uses access codes for its digital platform, Connect. Connect is not just a digital textbook, but also used for assessments.

Salewa Olawoye, a Ryerson economics professor, uses Connect’s online quizzes for her macroeconomics course. The weekly quizzes, that can only be accessed through Connect, account for 20 per cent of students’ grades.

Essentially, students are paying tuition, as well as extra fees to take quizzes.

Since it’s the university’s job, not a textbook publisher’s, to assess and grade students, the Ontario government has restricted how much third-parties can interfere.

According to the Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities, “Where a course relies on assessments that are included with a learning resource, such as an online textbook, the ministry expects colleges to have a policy with respect to their students’ interests.”

At the University of Waterloo, instructors are encouraged to only use access codes if the cost of resource is no more than $50 and the assessment counts as 20 per cent or less. If either cost and grade value are not met, the instructor must provide students with a free alternative, like writing the online quiz on paper.

At Ryerson, assessments through third-party vendors must not account for more than 25 per cent. But there is no cost restriction, or free alternative that must be provided. Professors can charge students any amount for an online resource that can impact their grade, as long as it does not exceed that 25 per cent.

But the shift into digital doesn’t have to be expensive—it can be free.

“What is difficult is that when a fee occurs, it is up to student associations or individual students to alert the province and push them to hold the institutions accountable,” Gayle McFadden, National Executive Representative of the Canadian Federation of Students says.

“This gets difficult when the province has little to no regulatory body to enforce, which is where lobbying efforts and a strong united student movement is critical to fight for student rights.”

But the shift into digital doesn’t have to be expensive—it can be free.

Amanda Coolidge is the Senior Manager of Open Education B.C., a source that provides free textbooks for educators and students to access online.

The textbooks on Open Education have an open license that allows anyone, including teachers, to obtain and distribute textbooks.

“The textbook industry has risen three times the rate of inflation in the last ten years,” Coolidge says. “Faculty is realizing that it’s costing their students hundreds and thou- sands of dollars just to use textbooks.”

Coolidge says that some authors have taken a stance on defending access to education by choosing to offer the textbooks that they’ve written with an open license The major publishing companies that dominate the market—McGraw-Hill, Pearson, Wiley and Cengage—say open textbooks do not threaten their commercial business.

“Their response is that you’re getting a much higher quality resource with Pearson or McGraw Hill which is false because it’s the same authors just choosing a different plat- form to deliver the material,” Coolidge says.

Leave a Reply