By Kelsey DeMelo

Five years ago at 6 a.m., a GO train heading towards Union Station from Markham carried a tired and anxious Jason Marlatt. It was just getting light outside, and he sat among adults on their way to work. Someday, he’d be one of them, but for now, he was just a student. He made sure to catch the earlier train so he would have time in case he got lost while finding his way to his first 8 a.m. politics lecture at Ryerson University. That September morning brought feelings of excitement and ambition for Marlatt as he was about to begin what he believed would be four exciting years as a history major.

Throughout his time at Ryerson, Marlatt has come to learn that university is not all smooth sailing. In his second year, he was put on academic probation. It was then that Marlatt realized he could do one of two things: work hard or drop out. He went with the first option. He decided to slow things down and take an extra year to finish his degree. Since then, his attitude has propelled him to continue in his program, but overcoming that obstacle has led him to another: finding employment after graduation.

Marlatt’s program doesn’t offer co-ops or many opportunities to put his skills to any real use, and in his fifth year, he is still far from feeling qualified to enter the job market.

Because of this, his four-year plan has changed. This means a potential two extra years and approximately $20,000 in tuition he wasn’t banking on. But to get his dream job—working with NGOs or development agencies—this is what he’ll have to do. He plans on taking a master’s degree in Islamic studies at either the University of Toronto or McGill University.

Unemployment, or underemployment, are serious obstacles that Marlatt has had to consider as he nears the end of his undergraduate journey. “The thought of not being able to find a job in my field keeps me up at night, but even worse is the thought that I could end up in a job I do not enjoy, but simply keeps me afloat,” says Marlatt.

Kids are directed towards university at a young age and told it’s the only way to succeed out there in the “real world.” This pressure can result in kids hastily choosing a program without considering where it will lead them in the future.

The initial thought for most students is that once they spend four years of blood, sweat and tears obtaining their bachelor’s degree, they’ll be qualified to enter the job market. The whole education path to success seems foolproof, doesn’t it? You pay big bucks to your institution and if you’re capable of handling the physical, mental and financial stress of being a student, they’ll reward you with a piece of paper that is supposed to guarantee that you’ll get a job.

But in the current job market, finding a young adult with a bachelor’s degree is as easy as finding a millennial who still lives with their parents. In 2011, Statistics Canada showed that 64 per cent of adults age 25-64 had post-secondary qualifications. Some students are realizing a bachelor’s degree doesn’t hold the same value as it once did, making it harder for them to compete for employment. That expensive piece of paper you spend four years of your life on is just an addition to your resumé, not a guarantee for successful employment.

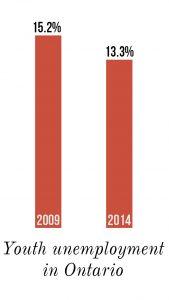

The unemployment rate for youth in Ontario has improved since the 2008-2009 recession, but not by much. In 2009, unemployment rates for the 15 to 24 year-old age demographic peaked at 15 per cent, according to Statistics Canada. And as of 2014, unemployment rates have slightly lowered to 13 per cent. But the underemployed rate—which applies to skilled individuals working low-paying or low-skilled jobs—was still a daunting 30.4 per cent in 2014. The unemployment and underemployment rates for youth prove just how overwhelming and intimidating the job market is for new grads, and why so many of them pursue grad school.

Nikki Waheed, a career education specialist for the Faculty of Arts at Ryerson, primarily works with arts students. She finds that the most common concern she hears is that these students don’t know what they can actually do with their arts degree or what jobs are available for them. This is where the idea of grad school often pops up.

Waheed says that the current job climate for new grads is definitely a major concern. A graduate degree on a resumé would certainly be an advantage for any student when it comes time for them to enter the job market.

While Waheed isn’t afraid to recommend grad school to those students who have a plan in mind, she is hesitant to recommend it to students who are scared to leave the safety of school and find a job. She says grad school is a serious commitment both time-wise and financially, and should be carefully planned.

Camilo Botero, a second-year urban and regional planning student at Ryerson, knows he will most likely have to get a master’s degree to find a decent job, which will take at least two more years. But he’s also doing it for the sake of his family. His parents moved their family from Ecuador to Canada when he was 12 years old with hopes that they would be able to make a better life for their children.

“The thought of not being able to find a job in my field keeps me up at night, but even worse is the thought that I could end up in a job I do not enjoy, but simply keeps me afloat”

“I’ve always felt pressure to succeed for myself but mostly for my parents because they’ve worked so hard to provide us with the life we have,” says Botero. But throughout Botero’s time as an undergraduate student, he’s come to realize that becoming successful is going to take a lot more time and money than he had ever expected.

Three years ago, on a cold Wednesday morning in October, Botero was not a Ryerson student.

He was a student at University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM) studying mathematics and statistics. And he hated it. When he first began university in 2014, he expected it to be a quick four years of studying before he’d be able to join the workforce with his fancy new bachelor’s degree. To him, this was the ultimate pathway to success—the only way.

On that Wednesday morning, Botero was working away on a coding assignment for his first-year computer science course. As he stared in dismay at his professor who was trying to explain the assignment, he suddenly felt unsure of “what the hell” he was doing and why he was wasting his time trying to obtain a degree he couldn’t care less about. Did he even really like computer science? Sitting there, he wasn’t so sure anymore.

It was that class that destroyed Botero’s ideal four-year plan. He knew he had to get out of that program and try something new, but he stuck it out for two more years anyway, before finding the courage to tell his parents he just couldn’t do it anymore.

At this point, Botero found himself drawn to the idea of helping the environment. So, he applied to Ryerson’s urban and regional planning program, but was extremely doubtful that his UTM marks would get him a spot. When he did get accepted, Botero was told that none of his credits would count toward his new degree.

When September 2016 came around, his four-year plan had become a six-year plan. He was less than happy about it but he kept going because this time he’d be getting a fresh start doing something he loved—hopefully.

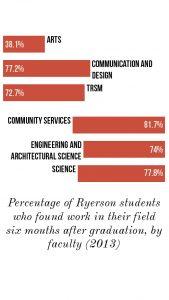

An arts student like Marlatt has a 38 per cent chance of finding employment in his field six months after graduation, according to Ryerson’s most recent employment data from 2013. Two years after graduation the chances increase to nearly 50 per cent.

The employment rates at Ryerson greatly vary from faculty to faculty. As of 2013, a student with a bachelor’s in engineering had about an 89 per cent chance of finding employment in their field, which is more than double of that for a student with an arts degree.

But in 2012, the Council of Ontario Universities reported that six per cent of youth that had a bachelor’s degree still couldn’t find employment.

That six per cent—no matter how small it may seem—is worrisome. What if after four years you come out still unemployable? That exact thought is what is driving so many new grads to go back to school and get a graduate degree.

Obtaining a master’s or graduate degree can add another two to five years of education on top of the four years it already takes to get a bachelor’s degree. Which means if you’ve planned everything just right, you’ll be in school for about 18-23 years of your life.

After all the time spent getting decorative diplomas, the real world is supposed to be your reward. But for a lot of students, there are many obstacles holding them back, such as the high cost of graduate school.

If all goes as planned, by the time Botero is done his undergrad and a possible two years of graduate studies, he will have spent $62,066.79 in tuition alone.

Botero, who has an older brother that has also undergone four years of undergrad, is hesitant to ask his parents for money for grad school. “School is definitely a financial burden and one I’d have to consider taking a year off or so to work,” says Botero. “But hopefully, going back to school will help guarantee that I’ll land a job I’m happy with.”

For many students that struggle to pay for their undergrad tuition, grad school may be a luxury that they cannot afford. According to Statistics Canada, the cost of undergraduate tuition in Ontario in 2016 was $8,114, meaning that four years of school will cost about $32,456. This doesn’t include the cost of textbooks, residence or commuting, and the general expenses that come with being a student.

So, after all that, students are still expected to obtain a higher and more valuable degree. In Ontario, the cost of grad school averages about $9,416 per year, but varies greatly depending on the program. Add that to the cost of everything else and you get another extremely lavish piece of paper to add to your collection.

But when he’s done, Botero will hopefully have a job that gives him a reason to get out of bed in the morning and fulfills his definition of success, for both himself and his family. He is optimistic that things will work out, even if it’s not in the way he had originally planned. It might take an absurd amount of his time and money, but one day, he hopes he’ll look back at his young and stressed student self and realize it was worth it.

For Botero and thousands of other students, before they can reach the success in the real world they will have to endure further stress and sleepless nights—the ultimate foundation of university.

Hunched over his design, trying to get every line, angle and shape perfect before the 9 p.m. deadline, Botero felt a massive wave of stress wash over him. In the fall of 2016, Botero sat anxiously in an architectural studio class at Ryerson. The room was dead silent, except for the scratching of pencils and the shuffle of paper. As he quickly glanced up from his work, he saw his classmates working fervently over their own designs. The bags under their eyes were deep and dark, and the exhausted expression that was painted their faces made it clear that they were just as anxious and sleep-deprived as he was. Because when there’s a lot to do, there’s no time for sleep.

It was in that quick, eerily quiet moment that Botero got a glimpse of his future and saw himself competing against these same classmates for the same jobs once he got out into the real world.

Everyone in the room has the same goal: to get a good job. And they’re all just as good as he is. They’ve taken most if not all of the same classes, and they’ll come out on the other side with the same degree. And if he wants a job, he’ll have to do better. Work harder. Stay in school longer. No matter the cost.

“Since everything is so damn competitive and not many jobs are actually available, it’s like I have no other choice but to go back to school after all this school.”

Leave a Reply